Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Once a glittering Tudor residence built for Henry VIII, this grand palace has long since disappeared from the landscape, but its legacy lives on. Over recent years, Surrey County Archaeological Unit (SCAU) worked in partnership with Elmbridge Museum to breathe new life into the vast and fascinating Oatlands Palace Archive. The project was not just about preserving the past, it was about rediscovering it.

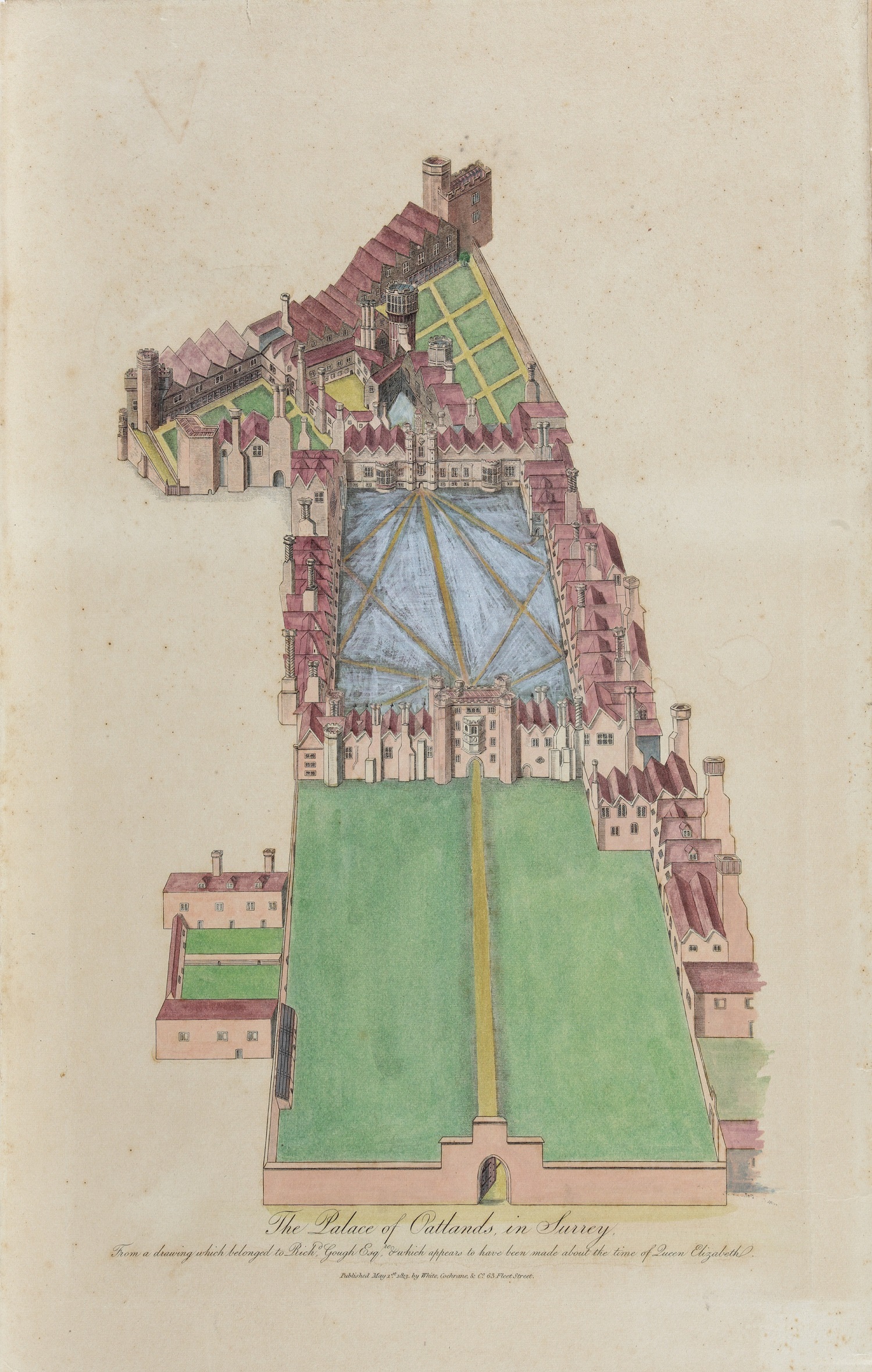

207.1964. Coloured print on board of the "Birds eye view of the Palace of Oatlands in Surrey", from a drawing which belonged to Richard Gough, Esq. which appears to have been made about the time of Elizabeth I.

207.1964. Coloured print on board of the "Birds eye view of the Palace of Oatlands in Surrey", from a drawing which belonged to Richard Gough, Esq. which appears to have been made about the time of Elizabeth I.

Oatlands Palace began its life in the late 13th century as a manor house. In the late 1400s, it was transformed into a substantial brick-built house by Bartholomew Read, a wealthy London goldsmith. When Henry VIII acquired the site, he expanded it between 1537 and 1544 into a grand royal residence. Oatlands soon became the queen’s palace, complementing Hampton Court (the king’s residence) and Nonsuch Palace (the prince’s).

Henry VIII’s vision for Oatlands evolved over time. The moated manor was drained to accommodate a new middle court and outer court, which housed royal apartments, kitchens, and domestic offices. The palace was occupied by several of Henry’s queens—including Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr—and continued to serve the royal family until it was demolished in 1650 during the English Civil War.

One particularly fascinating detail from the palace’s construction is what may be the earliest known instance of disabled access in a royal building. After a serious jousting accident in 1536 left Henry with a chronic leg injury, a ramp was installed at Oatlands to allow him easier access to the first floor. This thoughtful architectural adaptation offers a rare glimpse into the king’s later years and provides an early example of accessible design in a period not typically associated with such considerations.

Today, only fragments of the original structure remain, but what lies beneath the ground and within the archive tells a powerful story of Tudor ambition, innovation, and daily life.

Oatlands Palace excavations.

Between 1968 and 1984, a series of excavations revealed a rich collection of artefacts, from decorated floor tiles and carved masonry to more everyday objects.

Perhaps the most striking discoveries came from sealed garderobes, Tudor lavatories packed with objects from the 1640s, frozen in time when the palace was demolished.

Oatlands Palace archive at the Elmbridge Museum store.

These finds were stored in more than 160 boxes at the Elmbridge Museum store, alongside hundreds of paper records, site notes, architectural plans, and maps.

In 2012, a review identified the need to modernise the archive, and in 2019, it was transferred to SCAU at the Surrey History Centre in Woking. There, a new project was launched: the Oatlands Palace Archive Project.

The project officially began in January 2020. Each Wednesday, up to a dozen trained volunteers worked with SCAU staff to repackage artefacts, digitise records, and catalogue the collection.

Finds from the original excavations were being stored in envelopes, newspaper, shoe boxes, and even throat sweet tins, and the archive was in desperate need of modernising to meet current archaeological archive recommendations.

By March, volunteers had contributed over 470 hours of work. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic brought in-person sessions to a halt, the team quickly adapted.

Examples of packaging being used to store finds from the original excavations. Throat sweet tins, match boxes, fruit crates, and shoe boxes were all used.

Examples of packaging being used to store finds from the original excavations. Throat sweet tins, match boxes, fruit crates, and shoe boxes were all used. Volunteers began working from home, transcribing nearly 40 historical documents that included Tudor building accounts, worker wages, and even an inventory of Catherine Howard’s rooms drawn up after her execution in 1542.

These tasks added a further 165 hours of volunteer work during lockdown, from their own homes.

‘I spent a lot of time sorting out and archiving stained glass from the Palace. They were beautiful pieces, and the complete windows must have been stunning. I also spent time typing up handwritten reports which I found very interesting and often had to stop typing so I could read the reports first! Working with SCAU is an amazing experience and archiving Oatlands Palace was the best so far.’

Liz, Oatlands Palace Archive Project volunteer

SCAU Volunteer Liz repackages painted window glass from Oatlands Palace at home during Lockdown.

SCAU Volunteer Liz repackages painted window glass from Oatlands Palace at home during Lockdown. The dedication of the volunteer team didn’t falter. Volunteers continued contributing from home, typing handwritten box lists and even receiving deliveries of finds to work on remotely. By early 2021, over 1,030 volunteer hours had been logged. When restrictions eased, in-person sessions resumed in a COVID-secure format. Volunteers operated in small groups, with their own equipment and socially distanced workstations.

In just a few weeks, another 35 boxes of finds were repackaged, raising the total to 72 completed boxes before lockdown returned.

Volunteers working on the Oatlands Palace archive at the Surrey History Centre with safety measures in place.

Volunteers working on the Oatlands Palace archive at the Surrey History Centre with safety measures in place.  Stone and brickwork at the Elmbridge Museum store.

Stone and brickwork at the Elmbridge Museum store.

Every item was carefully unwrapped, recorded, and repackaged to meet modern museum standards. The project uncovered hundreds of fascinating artefacts—floor tiles, ornamental brickwork, iron tools, pottery —and linked these physical finds to documentary evidence from the Tudor period.

Some stone and brickwork was too heavy to be moved from the Elmbridge Museum stores, so volunteers carried out recording on site, counting, weighing and recording. Much of the stonework was originally from Chertsey Abbey, but had been re-used in the foundation construction of Oatlands Palace.

‘It was a privilege visiting the store as we were able to see the amazing stone sculptures which were far too heavy to transport to SCAU. We spent a few hours sorting through boxes of bricks, weighing each one and deciding which bricks should be retained and which could be disposed of. During COVID we typed the fascinating employment records.’

Rosemary, Oatlands Palace Archive Project volunteer

Volunteers also played a critical role in digitising and interpreting the paper archive. A spreadsheet of the 1537–38 building accounts was created, documenting the name of masons, carpenters, labourers, and even brick counts involved in constructing the palace. Drawings of architectural stonework were matched to written descriptions, creating a lasting research tool.

Screenshot of the Oatlands Palace Building Material document.

By the end of the project, almost 6,000 artefacts had been repackaged using stable, archive-grade materials. The catalogue was updated, the records were digitised, and the entire archive was prepared for its return to Elmbridge Museum.

Screenshot of the Oatlands Palace Building Accounts.

The completed archive now meets modern curatorial standards, ready to support future research, exhibitions, and education programmes.

From Tudor brickmakers to 21st-century volunteers, the legacy of Oatlands Palace has been preserved thanks to the care, skill, and enthusiasm of everyone involved.

The Oatlands Palace Archive Project showcased the power of community archaeology—how a dedicated team of volunteers, supported by professionals, can achieve remarkable results. It also highlighted the importance of adapting in challenging circumstances and finding creative ways to continue vital heritage work.

Now safely housed with Elmbridge Museum, the archive remains a testament to Surrey’s rich and complex history—and the people who helped uncover it, ready to be used by future generations for research and to learn about the past.

Surrey County Archaeological Unit logo

Surrey County Archaeological Unit logo

The Surrey County Archaeological Unit runs regular community archaeology sessions and welcomes new volunteers. Whether you’re a seasoned enthusiast or simply curious about the past, there’s a place for you to join in uncovering Surrey’s story. Email education.scau@surreycc.gov.uk for more information, or find Digging Surrey’s Past on Facebook or Surrey County Archaeological Unit on Instagram.

To explore more about Oatlands Palace and its excavations, you can purchase Excavations at Oatlands Palace from the Surrey Heritage online shop. You can also download the publication for free.

This blog was written by SCAU archaeologists and volunteers.

Click here to download the publication for free