Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

The colourful spectrum of protest witnessed by Elmbridge over the ages has ranged from peaceful objection to violent militancy. Although in many cases, movements were worlds apart – the 17th Century Diggers had vastly different demands to the 20th Century Suffragettes – the riots, rebellions and revolts all have one thing in common. Sparked by a deep-rooted anger at the status quo, every one of them is embedded in Elmbridge’s historical landscape.

The Look Back in Anger display at Cobham Library, 2020-21.

The Look Back in Anger display at Cobham Library, 2020-21.

Protest has brought about vital change for centuries. It comes in all different shapes and forms, but each act of opposition symbolises a cry of disapproval at the way things are.

Elmbridge Museum originally launched ‘Look Back in Anger’ as a display at Cobham Library in 2020-21. In this online exhibition, you can explore the objects which were featured in it and gain a glimpse into the history of a variety of campaigns in Elmbridge.

Below, we examine the root causes, wars of words and defiant deeds of activists across the ages.

Discover Elmbridge's most prominent past protests here, starting over 350 years ago and continuing into the present day.

The Diggers set up camp on St. George's Hill in Weybridge, under the leadership of Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard.

Charlotte Despard from Esher sets up the Women's Freedom League to campaign for female suffrage, and is supported by the Duchess of Albany based at Claremont. The Women's Co-operative Guild later descends from this organisation.

Radical Suffragettes Kitty Marion and Clara Giveen set fire to the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse, Molesey, causing major damage.

The 'Battle of Ditton' takes hold of Thames Ditton, as local residents fight against plans to develop the historic High Street there.

The development of the Esher Bypass causes a major dispute, in which local residents take significant action to try and prevent the loss of Common Land.

'The Land is Ours' campaigners set up camp on St George's Hill in Weybridge, on the 350th anniversary of the Diggers' occupation of the site. They were protesting about the restricted access to the land there and drew on the imagery and words of their predecessors.

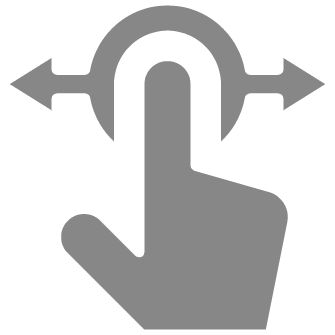

Miles Halliwell playing Gerrard Winstanley in the 1975 film ‘Winstanley’.

Date: April 1649

Leader: Gerrard Winstanley, a failed tradesman-turned-labourer from Cobham.

Roots: Winstanley claimed that the ‘Norman Yoke’ – the self-interested rule of the monarchy since the 1066 Norman Conquest – had given a select few vast powers to oppress the population. Then, when the English Civil War had raged between Parliament and the King from 1642, Surrey endured heavy taxation by Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentary forces on the promise they would reap the rewards later on. But when the Parliamentarians won and Charles I was executed in 1649, Cromwell’s assurance came to nothing. The Diggers finally formed to take action.

Words: In ‘The True Levellers Standard Advanced’, Gerrard Winstanley stated his Digger ideals. He believed that social hierarchies are wrong, and that all men are created equal with the same rights to use common land.

Deeds: A radical group of labourers occupied and dug the common land of St George’s Hill, Weybridge, in April 1649. They set up a commune there where everyone cooperated & lived equally.

The Diggers were eventually driven out by local authorities. They are now remembered across the globe in popular culture and are widely considered the proponents of the earliest form of Communism.

Find out more about the Diggers’ story in Elmbridge Museum’s Diggers Project.

Find out how you'd have fared in mid-17th century Elmbridge in our quiz!

Date: 1903

Leader: Emmeline Pankhurst

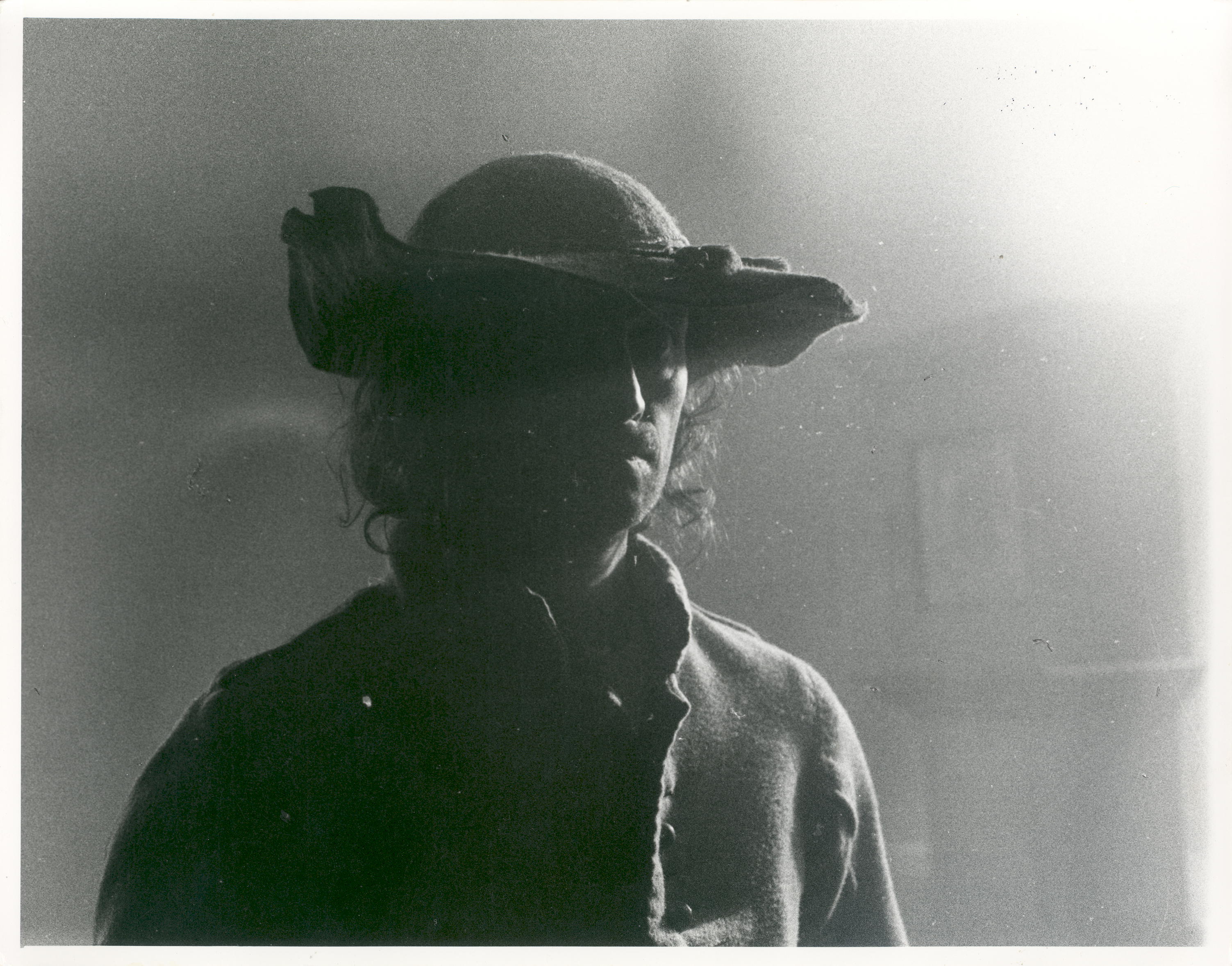

It was the long-term social and legal inferiority of women which inspired the start of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the 1800s. ‘Lady Audley’s Secret’ was noteworthy for challenging the traditional expectations of women – many of which are outlined in the more conservative ‘Woman’s Book’ (right). Emmeline Pankhurst became tired of how the peaceful methods of the Suffragists were not working, so in 1903 she created the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – nicknamed the Suffragettes. This was a militant organisation which used violent protest.

Find out more about local women's suffrage campaigners in Elmbridge Museum's 'Votes For Women!' online exhibition.

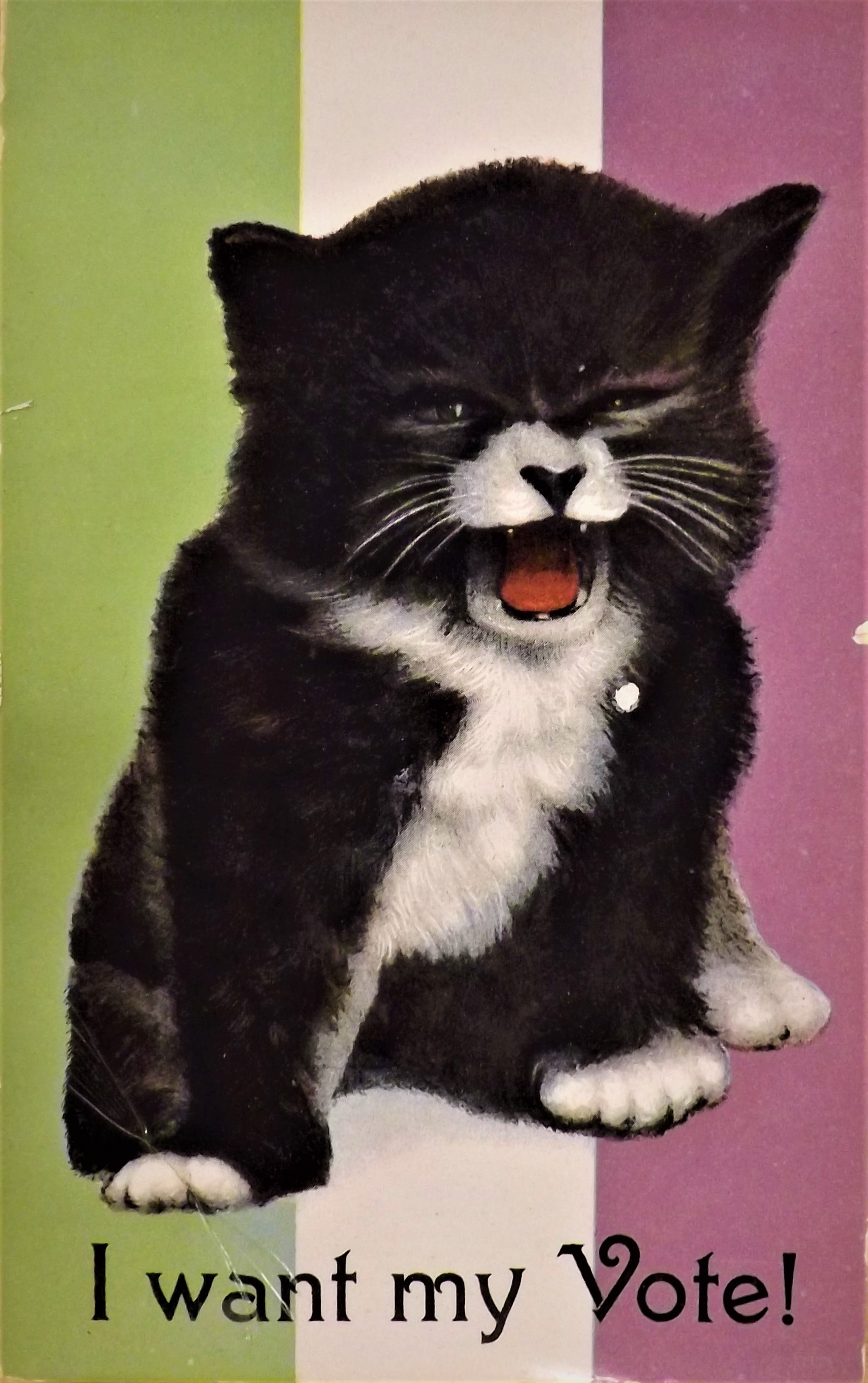

Their motto was ‘Deeds Not Words’, but they did use publications like ‘The Suffragette’ to get their ideas across and counteract the negative press they received. The postcard to the left mocks the Suffrage debate in print, showing Suffragettes as a hissing kitten. The former Holstein Hall in Weybridge was also regularly used for pro– and anti– Suffrage rallies and debates alike, in February 1910 and 1911 respectively.

Political satirical card of the suffragette period – Bulldog smoking a pipe, on Union Jack background, with the caption ‘Who said Votes for Women!!!’

Political satirical card of the suffragette period – Kitten, spitting, on green white and mauve striped background, with the caption ‘I want my vote!’

January 1913 – Letters were sabotaged in Weybridge by Suffragettes who poured ink into public letterboxes.

June 1913 – A fire at Hurst Park racecourse, started by hardened Suffragettes Kitty Marion and Clara Giveen, was the movement’s biggest attack in Elmbridge and cost £7000 to repair. It was a response to the death of Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison, who had thrown herself under King George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby on 4th June and died on the 8th.

July 1913 – The Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage (‘Great Pilgrimage’) saw thousands of suffrage supporters march two routes across the country. One of these march routes passed through Guildford, Cobham, Esher and Kingston, with debates held anti-suffrage protestors meeting the walkers along the way.

An image of the burnt grandstand at Hurst Park after Kitty Marion and Clara Giveen set fire to it in June 1913.

The Suffragettes paused their campaign from 1914 to help the First World War effort, and the right to vote was given to propertied women over 30 in 1918. The Surrey Herald reported that a Mrs. New was the first Weybridge woman to “exercise the new enfranchisement of her sex.”

Donald Macmaster’s political manifesto for Chertsey in the 1918 election also recognised that the war may have been a significant factor in some women gaining the vote, stating that:

“The Army of Women who have proved their capacity and discharged many of the duties hitherto entrusted to men need have no fear that their skill and diligence will be unrecognised. It is but just to say that during the last four years in the practical tests of war and civil life women have proved not merely their capacity, courage and powers of endurance but their title to share in making the Laws of the State and this title has just been affirmed by Statute.”

Banner from the East and West Molesey Women’s Cooperative Guild, an organisation descended, in part, from the Women’s Freedom League.

Date: 1907

Leader: Charlotte Despard of Esher. Despard was supported by the Duchess of Albany who lived close by at Claremont.

Roots: The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) started with a group of Suffragettes who had grown resentful of the WSPU’s violent methods. They sat half-way between the peaceful Suffragists and the militant Suffragettes.

Words: This group widely advocated direct disruptive actions in their various public speaking and debates and through their publication, ‘The Vote’. But they did not condone violence or attacks on property.

Deeds: In 1909, around 10,000 women boycotted the National Insurance tax on servant wages, with some facing prison sentences as a result.

In 1911, members of the WFL boycotted the census in an attempt to cause major disruption. They argued that women who couldn’t vote for the government had no obligation to participate in its census. Some women hid so they were not recorded in the census and some moved about so they were recorded in a number of locations – this is part of the reason why local Suffragettes are so hard to trace!

Charlotte Despard herself was arrested and imprisoned frequently, and admired by many Suffragettes. As a result, the WFL eventually had 64 branches.

During the First World War Years, when the Women’s Suffrage Movement paused its campaign Charlotte Despard turned her attention to supporting the Pacifist Movement (unlike many Suffragettes who were in favour of men signing up). When the vote was granted to some women in 1918, Despard stood as a Labour candidate in Battersea North, but did not win a seat in Parliament (the first and only woman to do so that year was Constance Markiewicz of Sinn Fein).

Alice Ruffle was dismissed as manageress of Frisby’s shoe shop in Weybridge at the end of the First World War. She set up Ruffle’s shoe shop directly opposite in opposition, and kept these boots behind the front desk for good luck. Her story is an example of how women stepped into new roles during and after the war – one of the most prominent reasons for then being granted the vote.

Discover more about Alice in our High Street Heritage Trail

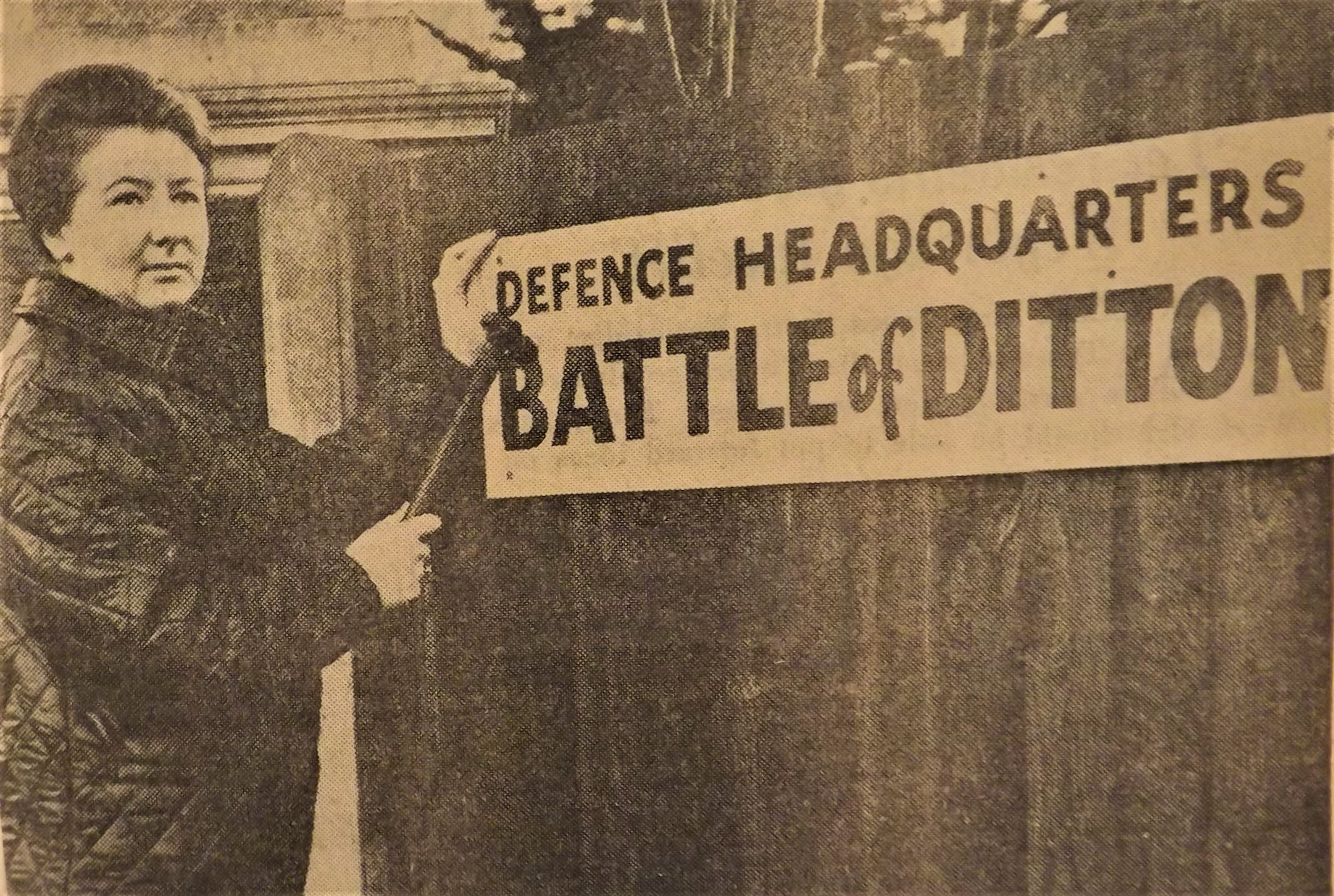

Photograph from a local newspaper reporting on the ‘Battle of Ditton’.

Date: 1966

Leader: Thames Ditton Residents’ Association

Roots: The local council’s plans to redevelop Thames Ditton’s High Street caused outrage amongst local residents, who rallied behind their local Resident’s Association to protest.

Words: The powerful language used to describe the non-violent spat in local and national newspapers (left) makes it particularly notable. In the press and local area the conflict became widely known as the ‘Battle of Ditton’, with numerous debates and angry meetings held over several months while the battle raged on.

Deeds: Esher Urban District Council was flooded with 300 letters from angry Thames Ditton residents. 4,500 people signed a petition against the development and activists set up a ‘battle’ base at a home in Thames Ditton.

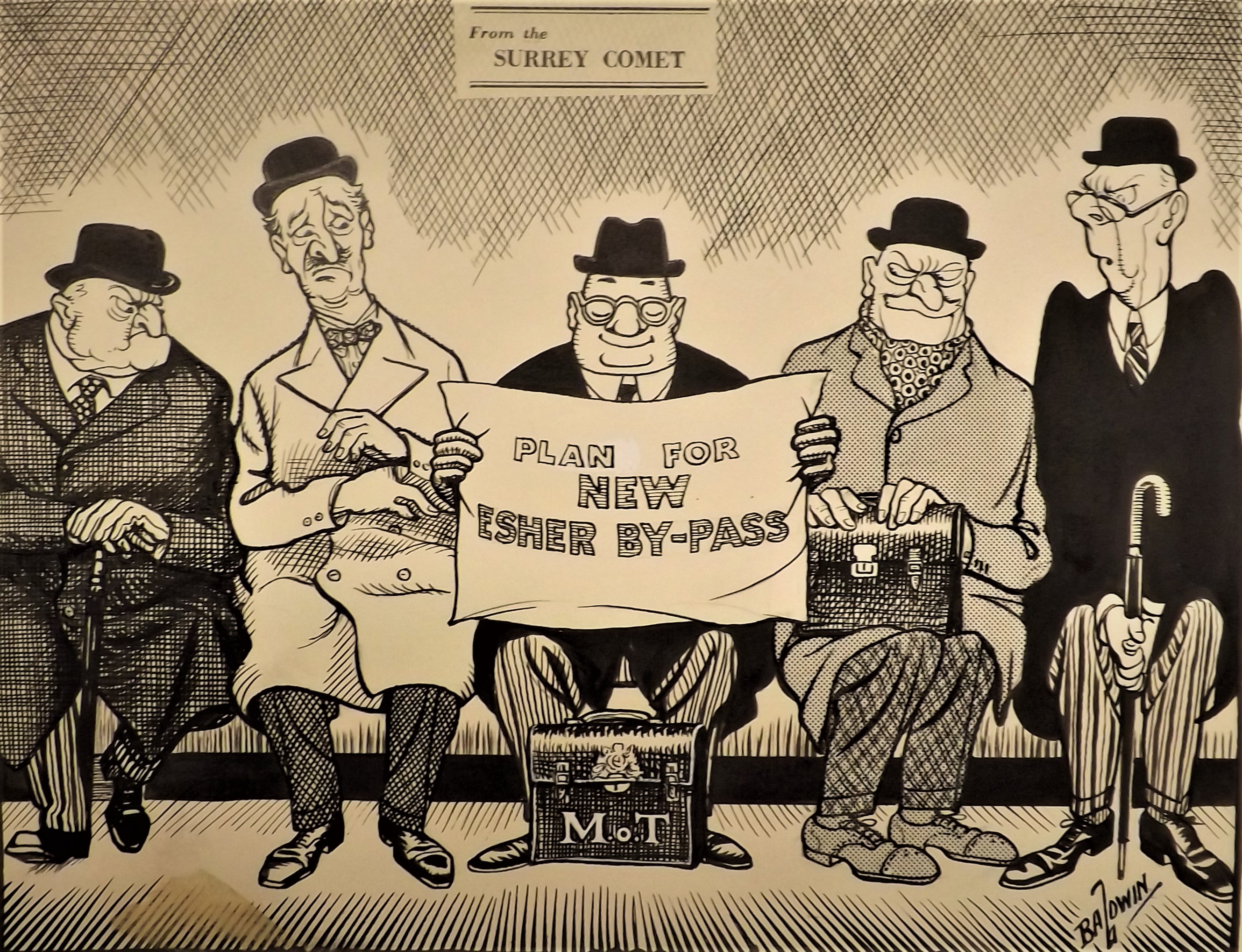

Cartoon from the Surrey Comet criticizing plans for the new Esher Bypass, 1974.

Date: 1974

Leader: Local residents, supported by the local press

Roots: The Esher Bypass had been in its planning stages prior to the Second World War, but was put on hold. The opening of Britain’s first motorway in 1958 marked the start of a huge programme for similar roads across the entire country, and by the 1970s plans for this huge road (part of the A3) were back on track.

Words: There was major discontent at the loss of Common land and woodland. To the left are a series of cartoons published in the Surrey Comet in 1974, mocking the Ministry of Transport and criticizing the plans for the Esher Bypass. Popular since the 1700s, cartoons often represent protesting voices through satire.

Deeds: After polite opposition through official channels failed, action was taken to oppose the construction by residents who regularly removed site markers on Esher Common, and making attacks on site equipment by draining the diggers’ fuel tanks or filling them with sand and sugar.

In 1974, the Esher Bypass was built across the middle of Esher Common. To try and compensate for the loss of Common land, 90 acres were added to the Commons in other areas (known as “exchange land”). After construction went ahead, local groups such as Cobham Conservation Group and FEDORA were formed by locals who had opposed the Bypass, with the objective of preventing further development on much treasured common land and historic local sites.

Traffic fills the roads with signs which read 'Esher Welcomes Piled Up Traffic', while ministers in old-fashioned clothes labelled names such as 'General Short Sight', 'Outdated Ideas', 'Self Interested Trader' walk along the pavement.

"We'll nip through the agenda before any of 'em wakes up". The Councillors are all asleep as the Chairman and Town Clerk "nip through the agenda" without them noticing.

Commuters are sitting in a train carriage looking angrily across at the Minister of Transport, who is reading the 'Plan for New Esher By-Pass'.

Date: April 1999

Leader: ‘The Land Is Ours’ group

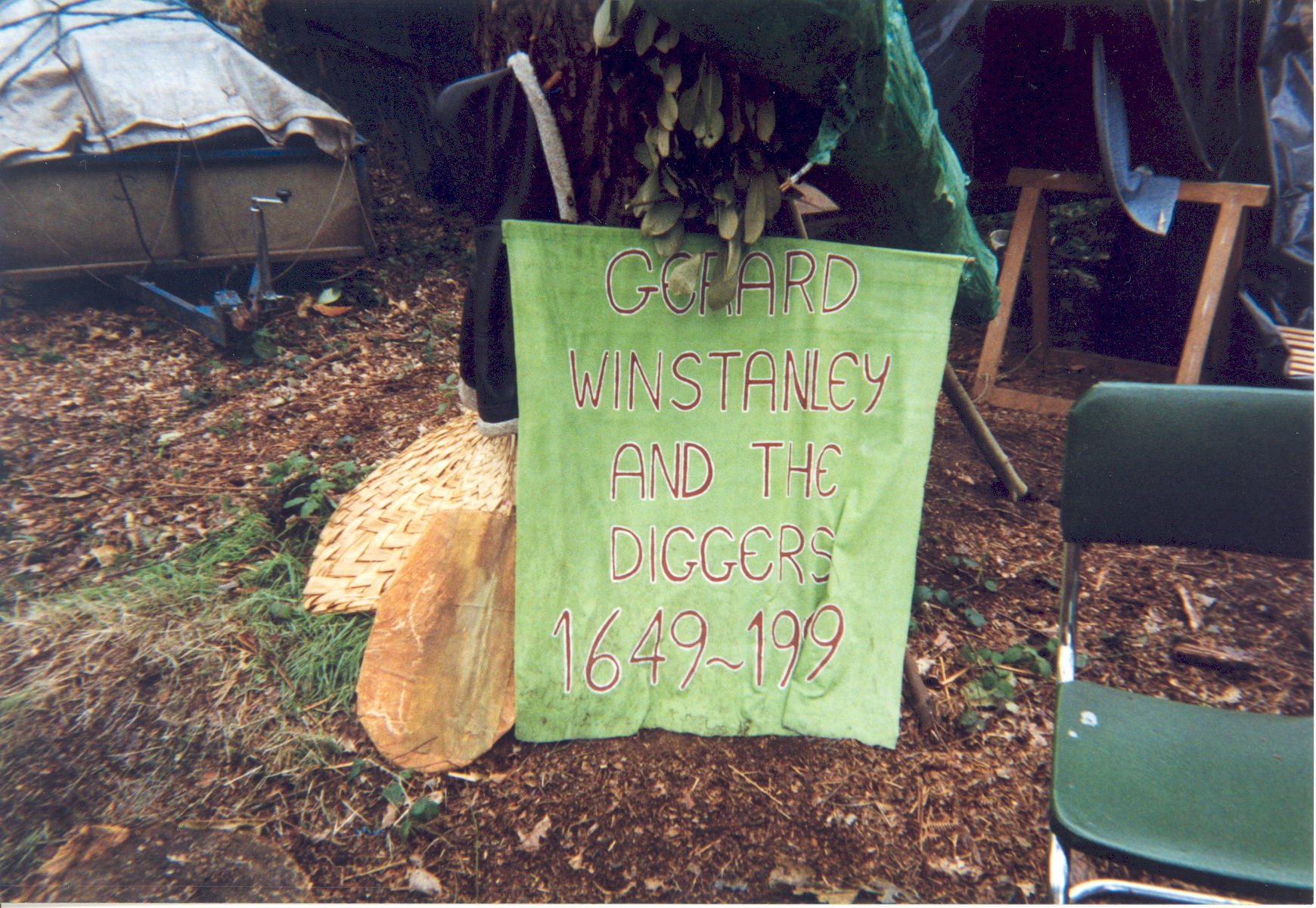

Access to land is an issue which has been raging on for centuries, and St. George’s Hill in Weybridge has found itself a particular focus for debates over public use of the land. The Land Is Ours Campaign used the Diggers of 1649 as inspiration for their protest in 1999, using many of the same arguments as their predecessors. They believed that the public had a right to access the common land in the now private gated community.

The entrance to the Land is Ours camp, April 1999. A gate with two large signs on it inscribed “Diggers Community” and “The Land is a common treasury for All”. Other colourful signs around the gate, and banners and bunting in the trees.

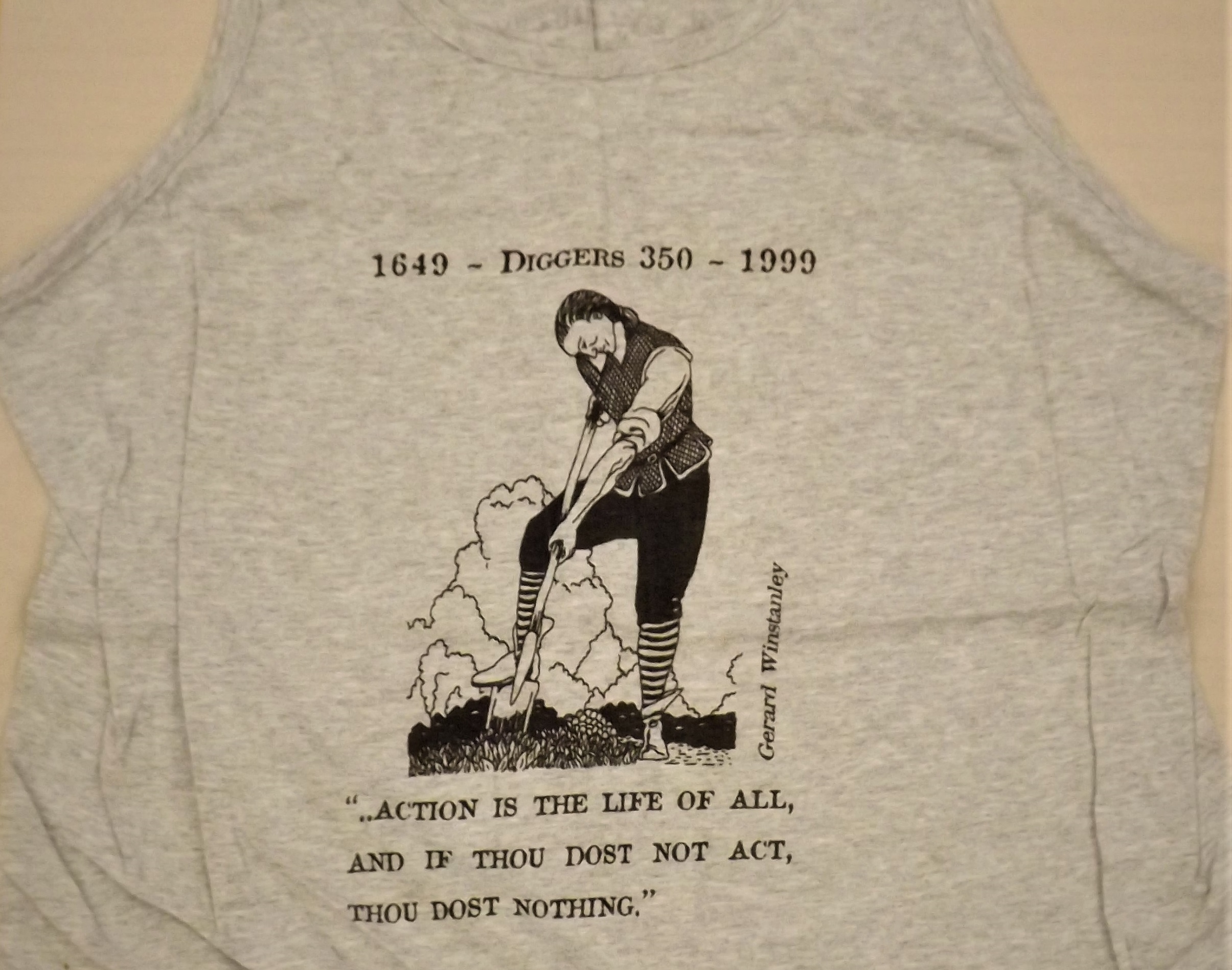

The organisers of this modern-day movement used many of the same words as the Diggers had done. They produced t-shirts and memorabilia with quotes from Gerrard Winstanley’s most famous writings printed all over them, and their campsite was adorned with references to the Digger Movement, with some participants even dressing up as 17th Century Diggers. In reality, much had changed since the Diggers – the historical context; the purpose of the protest; and the surrounding area were all vastly altered – and the two groups had very few similarities. But the sweeping parallels the modern movement attempted to draw were clear.

Photograph showing a green cloth banner inscribed in red: “Gerrard Winstanley And The Diggers 1649-1999”. From the Land is Ours campsite, 1999.

The front of a vest from The Land is Ours Campaign with Gerrard Winstanley quote ‘Action is the life of all, and if thou dost not act, thou dost nothing’.

Exactly 350 years since the Diggers set up their commune on St. George’s Hill, The Land Is Ours organised a march and set up camp at the same site. They faced extreme hostility from locals, who were sometimes even violent in their attempts to remove the group. Eventually, The Land Is Ours were forced to pack up and leave after a brief occupation, and St. George’s Hill remains restricted in access.

The Land is Ours Campsite at St. George’s Hill, April 1999.

Engraving of King Louis Philippe, the former King of France, in his obituary of 1850.

Engraving of King Louis Philippe, the former King of France, in his obituary of 1850.

Elmbridge even had a hand in revolutions across the channel. In 1848, a Mr and Mrs Smith set foot in Esher after travelling all the way from France. But this was no ordinary couple – Mr and Mrs Smith were the King and Queen of France.

When the February 1848 Revolution saw King Louis Philippe of France deposed in favour of a republic, he and his wife Marie-Amelie fled. They lived out their final days in safety at Claremont as the Count and Countess of Neuilly, with many of their relatives surrounding them in neighbouring boroughs and their residence often reportedly ‘full of French princes’. They became recognised members of the community and attended services regularly at St Charles Borromeo in Weybridge.

Louis died at Claremont on 26th August 1850, and he was initially buried in a mausoleum attached to the Catholic church of St. Charles Borromeo he had so regularly attended. Marie-Amelie lived on at Claremont until her death in 1866.

A fascinating record of Louis Philippe’s life at his Elmbridge refuge and funeral there have survived, pristinely preserved in our archive at Elmbridge Museum. Download it from the box below.

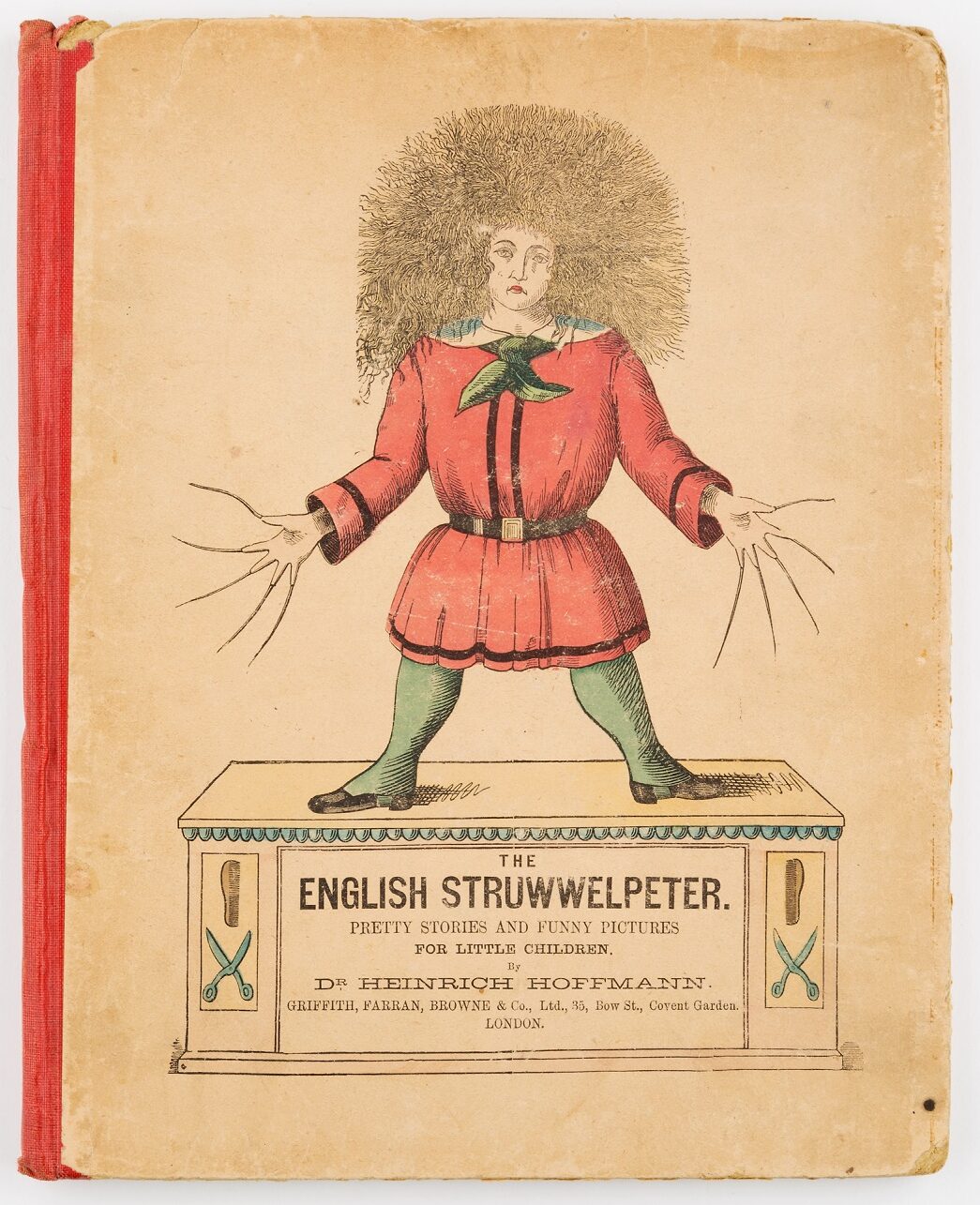

The original 'Struwwelpeter' in English.

The original 'Struwwelpeter' in English.

This edition of the famous ‘Der Struwwelpeter’ book was the first one published in English. Supposedly, author Heinrich Hoffmann was inspired to write the book for his children in 1845 after complaining about the lack of quality children’s books in the middle of the 1800s. Hoffmann certainly produced something with mass appeal, thanks to the way he combined catchy rhyming stories with exaggerated moral lessons.

The ten cautionary tales collected in the original Struwwelpeter not only tell of the gruesome ends of misbehaving children, but also show them with graphic and, somehow, comedic effect. Struwwelpeter was one of the first books that combined original stories and images together, paving the way for comics as well as a number of parodies.

But how does this children’s book relate to the protest and politics of the 20th Century?

There were many satirical parodies of the original Struwwelpeter, with a later British edition named ‘The Political Struwwelpeter’ mocking leading political figures of the day. The book was written by Harold Begbie and illustrated by F. Carruthers Gould in 1899. The new stories within this edition utilise both broadsheets and comic books to create a new type of literature aimed at adult audiences.

‘The Story of the High Flyer’ in this edition is of particular interest in the history of protest. It mocks the Archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple, who was at the time a vocal supporter of women’s rights to the vote, the movement for which at this time was heavily underway. Consistent ridicule like this fostered resentment and militancy within the movement.

Take a look at the beatifully illustrated ‘Story of the High Flyer’ in the downloads box below.

Illustration in 'The Story of The High Flyer', in The Political Struwwelpeter by Harold Begbie.

Illustration in 'The Story of The High Flyer', in The Political Struwwelpeter by Harold Begbie. Discover some of the beautifully illustrated, historical pages from Louis Phillipe’s obituary and ‘The Political Struwwelpeter’ here.

Elmbridge Museum’s Exhibitions & Interpretation Officer explains how this exhibition was put together. Including:

Want to know more about the most famous Suffragette attack in Elmbridge? Head over to our 'A Day at the Races' online exhibition to find out about Hurst Park and the aftermath of the huge fire. In our Ask the Expert video, historian Stewart Nash also illuminates some of the reasons that racecourses were a target for the Suffragettes.

Go to 'A Day at the Races'

Leave a Comment

Let us know your thoughts about the history of protest in Elmbridge here!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register