Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Surrey Herald and News. Friday 23 August 1968

Oatlands Palace was built in Weybridge by King Henry VIII in 1537 for his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. Over the years, subsequent monarchs used Oatlands until it was demolished in 1652. Since then, the land where the Palace once stood has passed through the hands of some notable owners.

Despite this rich past, little was known about the history of Oatlands Palace before its demolition. This lost landmark sparked local interest, and the Oatlands Palace Excavation Committee (OPEC) was formed. They conducted a series of archaeological digs between 1968 and 1973, and then again in 1983.

Featuring finds from these excavations, this online exhibition highlights the importance of amateur archaeology and provides a unique insight into what life was like at the Palace during Tudor times.

The site of Oatlands Palace in Weybridge was originally owned by Sir Bartholomew Read, a wealthy London goldsmith. In 1492 he began building himself a grand moated mansion surrounded by enormous fields and forests stretching from Walton to Chertsey. It was this house and surrounding land that King Henry VIII saw, and later bought, while travelling to Oatlands on a progress in September 1514.

Work to convert the manor house into a palace started in June 1537 as Henry wanted a home for his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, whom he married in 1540. However, this union was short-lived as the marriage was annulled six months later. The palace Henry built would become Oatlands Palace.

On the following pages you can learn more about the history of the Palace up to its demolition. To turn the page, click on the ‘next’ button or use the mouse to drag the page.

208.1964. Watercolour copy of Antonio Van Wyngaerd's drawing of Oatlands Palace, 1559. The original is in the British Museum.

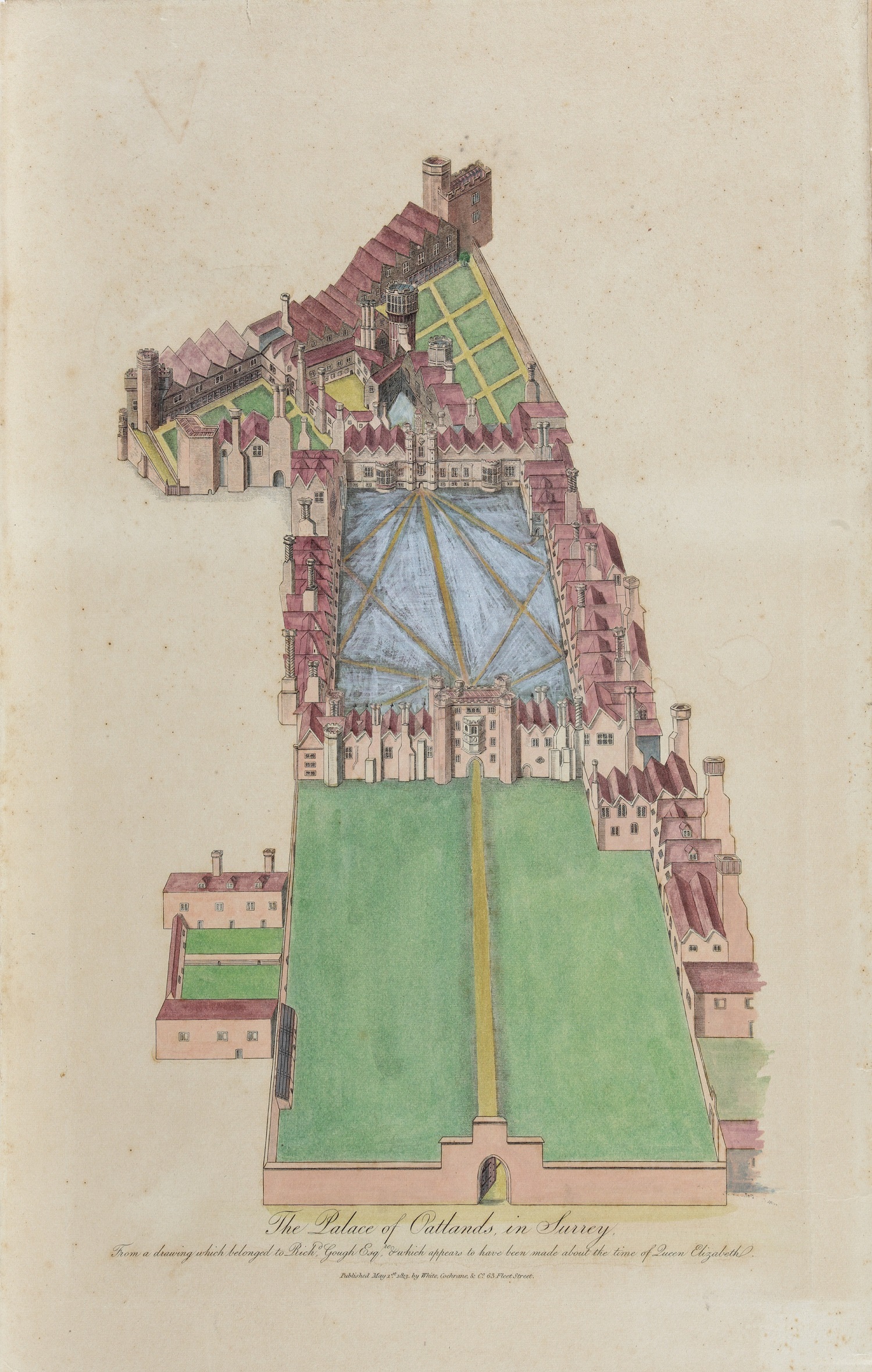

208.1964. Watercolour copy of Antonio Van Wyngaerd's drawing of Oatlands Palace, 1559. The original is in the British Museum.  207.1964. Coloured print on board of the "Birds eye view of the Palace of Oatlands in Surrey", from a drawing which belonged to Richard Gough, Esq. which appears to have been made about the time of Elizabeth I.

207.1964. Coloured print on board of the "Birds eye view of the Palace of Oatlands in Surrey", from a drawing which belonged to Richard Gough, Esq. which appears to have been made about the time of Elizabeth I.

The building of Oatlands Palace was part of the much larger programme of palace building undertaken by Henry VIII in the latter part of his reign.

With Henry’s health in decline, it became difficult for him to travel to his favourite hunting ground in Woodstock, Oxfordshire. So, as King of England, he decided to create a new hunting ground that was much closer to London.

In 1539 an Act of Parliament, The Honour of Hampton Court, was passed. This gave Henry rights to land and game that surrounded Hampton Court Palace. This Act also included the construction of two new palaces that would surround and link together this new hunting forest. King Henry would remain at Hampton Court whilst his wife would be across the River Thames at the remodelled Oatlands Palace. Nearby in Cheam would be Nonsuch, the residence of the Prince of Wales.

Nonsuch Palace was so-called because there was ‘none such’ place like it. It was a unique building and an example of early Renaissance architecture in England.

‘The Nonsuch stuccoes were unique and priceless treasures, the most important and striking component in the adornment of the first English building to be decorated largely in the Renaissance manner, and their destruction was ruthless and wanton.’ John Dent

Construction of Nonsuch began in 1538 and it remained a royal residence until 1682-3 when it was given to King Charles II’s mistress, Barbara Countess of Castlemaine. Sadly, she demolished Nonsuch to pay off her gambling debts. Although Nonsuch Palace no longer stands, the land which surrounded it does. This is Nonsuch Park.

Subsequent monarchs made considerable use of Oatlands. Later in the Tudor period, King Edward VI stayed at the Palace while the new Prayer Book was being debated at Chertsey. Queen Mary I retreated to Oatlands after her phantom pregnancies. Her sister, Queen Elizabeth I, hunted deer in the Palace grounds:

‘Her majesty is very well, and exceedingly disposed to hunting, for every second day she is on horseback, and continues the sport long. It is thought she will remain at Oatlands till the foul weather drives her away’. (Rowland White, an Elizabethan official, 1601).

The dawn of the Stuart era saw Oatlands Palace change again. King James I built a silkworm room and filled the Palace gardens with ‘rare trees, shrubs, herbs and flowers.’ His wife Anne commissioned Inigo Jones to design an ornamental gateway from the Privy Gardens to the Park grounds. She was also responsible for ‘the making of a new brick wall … to enclose her majesties vineyard at Otelands.’

In 1625, Charles I became King and gave Oatlands to his queen, Henrietta Maria. She used the Palace as a country retreat and art gallery.

391.1979/2. Black and white print on card of a drawing for a ‘Design for a Gateway at Oatlands by Inigo Jones’.

391.1979/2. Black and white print on card of a drawing for a ‘Design for a Gateway at Oatlands by Inigo Jones’. The English Civil War was fought between King Charles I and Parliament for ten years (1642 to 1652). The War was centred around religion, the King’s economic policies and use of power.

After years of fighting, the victorious Parliamentarians sentenced Charles I to death in 1649. With no royal family, this is the only period of republican rule in British history! During this time, Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. This period lasted until 1660, when Charles’ son was restored to the throne as King Charles II.

The Civil War was disastrous for England’s royal palaces, including Oatlands. After the King was executed, the Commonwealth Government sold Oatlands (and many other royal residences) to help pay parliamentary debts. Robert Turnbridge bought Oatlands Palace for £4,000 and demolished it in 1652. He then sold its bricks to Sir Richard Weston, who used them in the making of 12 locks for the River Wey Navigation.

Today, all that remains above ground of Oatlands Palace is the Tudor gateway in Palace Gardens, Weybridge. The original bricks remain in the locks on the Wey Navigation Canal (owned by the National Trust).

Oatlands Palace excavation.

Oatlands Palace excavation. Hampton Court Palace still stands majestically. However, knowledge of Nonsuch and Oatlands Palace was somewhat lost to history. In the 1960s however, archaeologists began digging at the remains of Nonsuch Palace. This sparked an immediate interest for nearby Oatlands Palace.

In 1968, the Oatlands Palace Excavation Committee (OPEC) was established under the chairmanship of Sir John Summerson and excavations begun. The Palace’s exact location and Henry’s adaptions to the original manorial structure were the issues that this first set of digs sought to address. The results obtained were so rewarding that further seasons of work continued until 1973.

Oatlands Palace Excavation Committee (OPEC)

The 1983 and 1984 excavations took place under very different circumstances. The housing estate which sat above the middle and upper courts of the Palace was due to be demolished and developed. This gave OPEC another opportunity to conduct research excavations. However, this time, the primary aim was to record as much as possible of the archaeology that would be destroyed in building works.

Sheila Richardson, archaeologist. Surrey Advertiser, 1968.

Take a closer look

Read the permission letter that OPEC sent to local residents before conducting the excavations.

Elmbridge Museum cares for the large archaeological archive and material collected during the excavations of 1968-1973 and 1983-1984.

In 2019, these finds were moved from the museum’s store to the Surrey History Centre (Woking) so that they could be worked on by volunteers within the Surrey County Archaeological Unit (SCAU).

Tasks involved re-bagging artefacts, digitising index cards and cataloguing the archive. Supervised by professional archaeologists from SCAU, volunteers began work in January 2020 and completed 430 hours within three months.

To turn the page, click on the ‘next’ button or use the mouse to drag the page.

Volunteer working at the Surrey History Centre with safety measures in place.

Volunteer working at the Surrey History Centre with safety measures in place.

With the announcement of lockdown, their work moved online. Excavation notes were scanned for volunteers to transcribe at home.

These documents contained a wealth of information, including the names of the men who built Oatlands Palace back in 1537.

Following the easing of COVID restrictions SCAU volunteers eventually returned to the Surrey History Centre, albeit this time with several safety measures in place.

In 2024, the project was completed. Across the Oatlands Palace Archive Project, 4525 hours or 628.5 days were volunteered by SCAU members.

Elmbridge Museum is indebted to the enthusiasm and commitment of volunteers in bringing the Oatlands Palace excavation back to life.

Volunteers working at the Surrey History Centre.

Volunteers working at the Surrey History Centre. The excavations of Oatlands Palace produced a diverse range of artefacts. Many of these are of intrinsic interest and, with the help of the SCAU volunteers, have shaped our understanding of Tudor life in Weybridge. Some of the finds can be explored below.

Pipkin cooking pot

Pipkin cooking pot

A pipkin is an earthenware lidded cooking pot with a hollow handle and three short legs. They were primarily used for cooking over coals or a wood fire.

The hollow handle would allow for easy manoeuvring with a stick. Several examples (complete or fragments of) were unearthed at Oatlands.

Similar examples have been found at Basing House (Hampshire) and Farnham Castle.

Bellarmine Jug

Bellarmine Jug

Bartmann jugs, also known as Bellarmine jugs, are a type of stoneware vessel that originated in the Rhineland region of Germany during the 16th and 17th centuries. Stoneware was a key export product from Germany during this time and was shipped across Europe, Britain, and later to colonies in North America and Asia. As seen from the photos, these vessels are typically salt glazed. They were commonly used for storing and transporting liquids such as wine, beer, and spirits.

The name ‘bartmann’ means ‘bearded man’ in German and this refers to the bearded man present on the lower neck of the vessel. It is thought that this figure is a satirical reference to Cardinal Robert Bellarmine – a Catholic figure who was unpopular amongst Protestants at this time. However, the jugs themselves were not originally intended to represent him.

The Oatlands Palace archive contains several whole Bellarmine jugs and many fragments. Compared to other sites in Britian (where there are usually only one or two vessels), Oatlands has an impressive number. There are around 35 masks/faces (or fragments of) and around 50 medallions (or fragments of) which would have decorated the jugs. This staggering number hints at the opulent lifestyle at Oatlands Palace.

What goes in, must come out!

One of the commonest glass vessels in medieval England was the urinal, and some people had several. Edward I had two and Henry VIII had no less than seven. This explains why so many have been found in English excavations, including Nonsuch Palace.

Several urinal fragments dating from the 17th century were found at Oatlands. When complete, these would have had a spherical body and a long cylindrical neck.

Uroscopy was an important part of medieval medicine. During the Tudor period, the colour and condition of urine was very important in diagnosing health problems. For this reason, the green glass was blown so thinly that it almost became clear. This allowed doctors to more accurately determine the colour of urine, but it also created a very unstable vessel. Its fragility meant that urinals were stored in cylindrical basketwork cases and hung by loop handles until ready for use.

Hearty food and meals were not the only status defining symbol in Tudor times. Tobacco was also an expensive luxury. Clay pipes were first smoked in England when tobacco was introduced from Virginia in the late 16th century. It was a fashionable habit and soon spread across the country. By the mid-1650s, the manufacture of clay pipes was an established trade, and farmers were cultivating fields of tobacco here in England.

Hundreds of clay pipes were excavated from Oatlands Palace, many mirroring changes in pipe design and smoking habits throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Explore a selection of the different kinds below.

As with other palaces built by King Henry VIII, Oatlands was typical in Tudor design with a strong emphasis on symmetry, balance and order.

It was originally thought that most of the building material for Oatlands came from the dissolved abbeys of Abingdon, Bisham and Chertsey. This is ‘monastic’ rubble. However, as the excavations developed, it became clear to archaeologists that palace builders used lots of different types of brick.

The building accounts from 1537 show that supplies of brick were collected in small quantities from lots of different sources. Four of these were directly from local kilns; John Aboroke’s at Kew, Master Carleton’s at Walton, and from John Chyrchea Junior and Thomas Nortryge, in Chertsey. Bricks also came from the royal houses at Hampton Court and Woking. In total, 331,878 bricks were delivered to Oatlands in 1537.

Explore the 1537 building accountsMany of the floor tiles excavated from Oatlands Palace belong to the type known as ‘Chertsey’ as they came from the nearby and dissolved, Chertsey Abbey. The King’s builders had salvaged the remarkable floor and wall tiles, which once illuminated the corridors of the Benedictine monastery, to beautify Oatlands Palace. These tiles were made on site and for the abbey exclusively. Remarkably, the abbey tiles have also been found at other sites in Surrey and Hampshire, and as far as Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire and Cheshire. They tended to be manufactured locally at the sites where they were going to be used and were not available on the open market.

Oatlands Palace was also decorated with Penn tiles. Tile makers in Penn, Buckinghamshire, were designing and firing tiles in the mid-14th century. Unlike Chertsey tiles, Penn tiles were sold to any buyer. Distribution of the Penn tiles extended through Buckinghamshire, London and Guildford. Chertsey Abbey was also a customer.

On the following pages you can explore some of these floor tiles found at Oatlands. To turn the page, click on the ‘next’ button or use the mouse to drag the page.

In the 19th century, women were discouraged from pursuing interests in archaeology as it was often seen as a male field. Women faced barriers to entry and recognition. Over time, attitudes towards women have shifted positively and women have made groundbreaking contributions. The number of female archaeologists has been steadily increasing and today women make up a significant proportion of the archaeological workforce. The same is true at the Oatlands’ excavations as some of the most important people involved were women.

Sheila Richardson handing an almost complete vessel of Bellarmine ware to Mr. Brian Blake, 1968.

Born in Walton in the 1920s, Sheila served her local community her whole life. She was educated at Danesfield School and joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service during the Second World War.

After the War, she studied horticulture and worked as a gardener, lecturing widely.

As an enthusiastic amateur archaeologist, she dug at Nonsuch Palace in the 1960s before joining the team leading the excavations at Oatlands. Alongside Mrs Margaret White and Mrs Cynthia Holmes, Sheila worked to sort, catalogue, record and manage the Oatlands excavations between 1968 and 1973. She was OPEC’s first Secretary and, over time, became a Tudor expert. Her knowledge was plentiful and well-respected, even advising the architects who designed the new housing development on the Oatlands site.

In addition to her archaeological work, Sheila was a volunteer at Elmbridge Museum for over 20 years and played a vital role in supporting local fundraising organisations. She died in St Peter’s Hospital, Chertsey, in 1987.

Avril looking over the Oatlands Palace excavations

In the 1970s, Avril was curator at Elmbridge Museum, then known as Weybridge Museum. She was a huge influence on the museum, championing immersive learning with her historical reconstructions and interactions with children.

Alongside her museum work, Avril was Secretary of OPEC (taking over the post after Sheila became ill) and worked tirelessly to save the archaeological finds from Oatlands Palace.

Her husband was an active photographer and made extensive photographic records of the Oatlands digs.

Other notable women involved were Margaret Angus (Site Supervisor from 1969), Madeleine Combie (responsible for much of the post-excavation work of 1983) and many other female OPEC and SCAU volunteers.

Oatlands Palace excavations.

Oatlands Palace excavations.

The archaeological excavations at Oatlands Palace have provided us with a unique insight into what life was like at a royal palace and in Tudor Weybridge.

The excavations, and recent work conducted by SCAU, show that the building and contents of Oatlands Palace cannot be studied in isolation. The strong architectural and structural links between the three sites highlight that Oatlands possessed its own character, but one which was also reminiscent of Hampton Court and Nonsuch.

Amateur archaeology remains an important lens through which to study the past and has greatly enhanced our understanding of these three palaces.

Elmbridge Museum would like to thank all the staff and volunteers involved with the Oatlands Palace excavations and SCAU Archive Project. Without their time, knowledge, and dedication, we would not have the access to or a greater understanding of our nationally significant collection that is the finds of Oatlands Palace.

Download a free copy of the publication ‘Excavations at Oatlands Palace’ here: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1220727

Alternatively, you can purchase the publication hereInterested in learning more about Elmbridge's Tudor past?

Leave a Comment

Let us know your memories of the Oatlands Palace archaeological digs and thoughts on the exhibition in this section!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register