Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

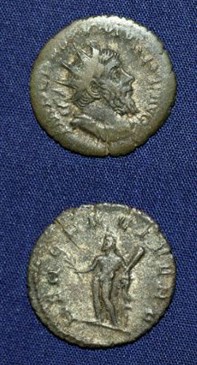

Two sides of a coin from Roman Britain, Antoninanus, AD 256 – 68.

Two sides of a coin from Roman Britain, Antoninanus, AD 256 – 68.

The arrival of the Romans had a large, lasting impact on society and culture, which can still be seen today.

The discovery of Roman coins dating from before the invasion show that trade had long existed between Britain and the Roman Empire before the invasion. Once the Romans landed on British shores in AD 43, they began to influence native culture, including technology, food and cultural practices. The settlers built bath houses and communal bathing was soon embraced by wealthier Britons.

The story of the Roman invasion in Elmbridge is an interesting challenge. With no Roman roads constructed in the local area during the early part of the settlement, citizens were largely unaffected by Roman life for a long time. The Romans did, however, pass through Surrey, and Cobham was a mere stone’s-throw from the major Roman road from London to Winchester.

What did slowly begin to happen is a British appropriation of Roman life, known as Romanization. It would nevertheless be inaccurate to see the Romanization as a purely one-way exchange. In the years following the invasion, both Britons and Romans adopted and took on aspects of the others’ culture which were attractive or useful to them. What resulted, therefore, was a tale not so much of the Romans themselves as of a very distinctive Romano-British hybrid culture.

Expensive Roman items such as accessories and jewellery has been found widely in excavations across Elmbridge.

We know a lot about Roman finery from the excavation of Roman and British graves. Wealthier Romans and Britons, both female and male, were buried with jewellery. Excavated bath houses, in particular, are also often awash with these kind of finds.

By using bath houses as a lens through which to view Romano-British life, we have a fantastic opportunity to see what it was about Roman culture that the Britons found so attractive. Used mainly by the wealthy, we can assume that patrons of the bath house wanted to show off their money and status.

In the museum there is an assortment of locally-found jewellery, alongside Roman coins, which were all uncovered at a Roman bath house in Cobham. It is therefore highly likely that bathers would have worn their finery to socialise there.

A flue tile from Chatley Farm Roman Bath house.

A flue tile from Chatley Farm Roman Bath house.

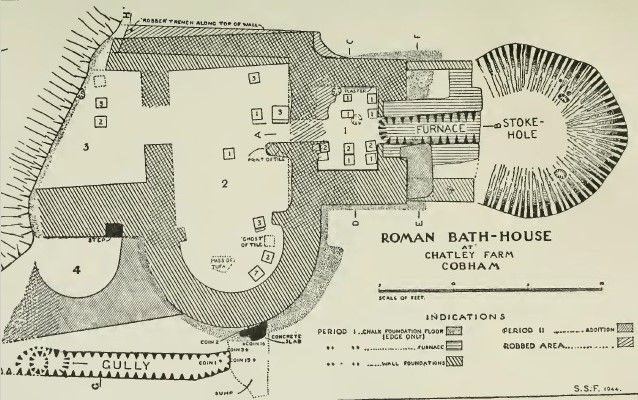

The remains of the local Roman bath house at Cobham were found east of Ockham Common in 1942. The Chatley Farm bath house, as it became known, was excavated by a team led by Surrey Archaeological Society.

The bath house was built in around AD 320 and used for about 40 years, up until AD 360, but we don’t know a lot about the people who visited other than the fact that many were wealthy.

Curiously, the remains of a villa which we know stood nearby have never been found. The settlement may have been washed away by the path of the River Mole over the years.

How did the Bath House work?

We do know that, like all Roman baths, visiting the Chatley Farm bath house was as much about socialising as washing. Bathing was a communal activity that gave people the opportunity to meet friends and catch up on news. Unlike today, the bather would pass through several different rooms to cleanse the body in stages. Upon entering the bath house, visitors would firstly deposit their clothes in the Apodyterium, which was a dressing room situated just inside the entrance to the building.

The Chatley Farm bath house used warm air, heated by a furnace and carried via flue tiles. A water tank called the Vasarium rested above the furnace to supply hot water to three of the four distinct rooms.

Copy of a plan of the Roman bath house. The uses of the main rooms labelled from 1 to 4 are outlined in the section below (Original by Tony Hallas).

We know that the bath house suffered from an initial poor design. There is evidence of a disastrous episode when the water tank melted, pouring molten lead, unsuited to high temperatures, into the surrounding stone. It is a possibility that the bath house was built by native Britons who wished to imitate a Roman lifestyle, but were still learning how the design worked.

Through such diverse Roman finds – bracelets, bottles pottery and architecture included – we can gradually begin to draw a narrative on the people who used them. The echoes of these past people are sometimes extremely tangible. Incredibly, the finger prints of ancient Elmbridge settlers still mark many tiles found at the bath house.

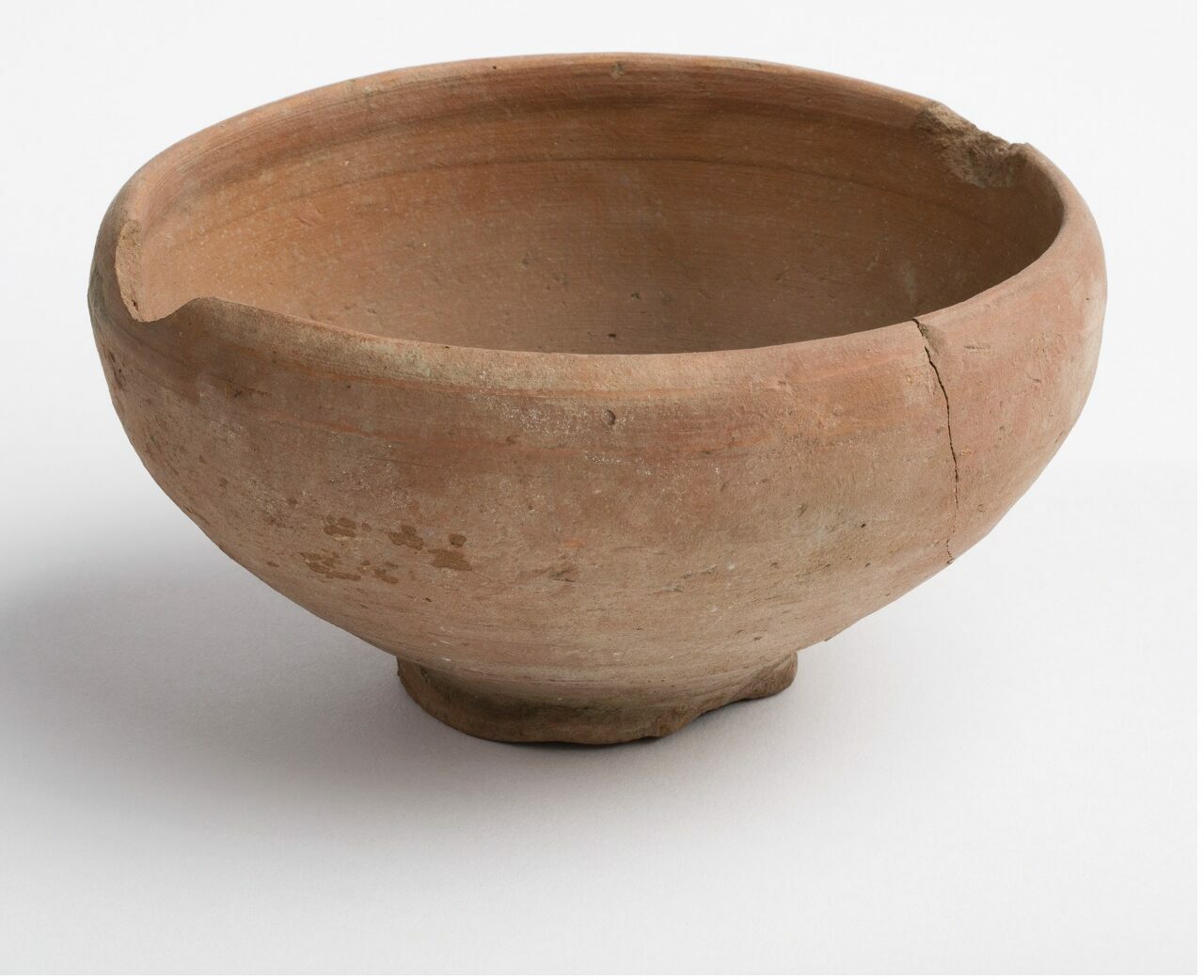

Dish with an inturned rim from the Late Roman Empire.

Dish with an inturned rim from the Late Roman Empire.

The Romans influenced other parts of life in the local area, including farming and cooking. The discovery of a Roman grain drier at Hurst Park in Molesey shows how the settlers introduced new technology. It made food production quicker and avoided grain spoilage, although it is true that many native British farming practices were still effective and continued unchanged.

We can see the Roman influence on the British diet from pots and vessels used for food and drink. The introduction of the mortarium, a bowl used to grind up herbs and spices ready for cooking, reveals the new flavours they introduced. There is an example pictured to the left. The Romans enjoyed using lots of different ingredients in their meals and introduced new foods to Britain. These include many things we still enjoy today: vegetables such as onions, garlic and peas, and herbs such as rosemary, thyme and basil.

One of the reasons Romanization was a success is that that Britons were willing to adopt this new culture. The Roman customs represented here may in many ways have seemed more advanced than native practices, and in lots of cases they presented new ways of undertaking traditional tasks. However, the overall cultural change was ultimately only ever partial, and very gradual. The influence was also two-way, with Romans taking on British methods too.

The Romans not only built a lot during their stay in Britain, but they seemed to reuse quite a bit as well. This tile, found at Cobham’s Chatley Farm bath house, is a great example of a patterned tile.

Roman Tile from Chatley Farm bath house. The unique marks from the die can be clearly seen as wavey lines across the surface.

Tiles were often cast in ‘dies’. Similar to a kind of stamp, these specially carved tools would impress decoration onto the clay tile to give it a particular shape or pattern. Dies and tile designing tools have been found in an Ashstead villa and brick-making site that was abandoned 150 years before the Chatley Farm bath house was built at Cobham. This suggests that patterns were often kept, rediscovered or reused later on by both Romans and Britons.

Different patterns from eight separate dies were discovered on tiles at the Chatley Farm bath house. This variety of tile finds is exceptionally rare, as most sites unearth no more than five different patterns or types of tile.

There is evidence of Romans taking on British techniques in other areas of Elmbridge too. Milling in Roman Britain was done using a two-part stone system. The stationary base, called a quern stone, laid flat while an upper hand stone was rotated against it with a wooden axel through the centre. This method of grinding flour from cereals dates from before the Iron Age, and the Roman example pictured below, found at the site of Hurst Park and now in Elmbridge Museum’s collection, shows that the technique continued for hundreds of years.

Why not take a look at our collection online, and uncover many more objects related to Roman life and culture?

Click here to search the Roman collections

Leave a comment!

Let us know your thoughts on Roman Cobham.You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register