Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

In the peak years of the British Empire, an understanding of the rule of empires was intrinsic to the way most people viewed the world they lived in. Notions of imperial prestige and expansion, and pride in Britain’s own far-reaching Empire, were pushed forward through a variety of propaganda tools, becoming heavily entrenched in the national consciousness as a result.

Unlike domestic items, buildings, or monuments, historical thoughts can be elusive. A mostly supportive press provides perhaps the clearest outline of popular thoughts and attitudes towards the British Empire, and in Elmbridge Museum’s own collection, strands of pro-imperial thought can be picked up in a number of objects.

Schooling, especially in the topics of history and geography, often endorsed the view that the British Empire was a positive force in the countries it controlled, and part of the natural order of the world. Royal tokens were also heavily linked to the British Empire, with coronations, jubilees, and other royal events acting as a vehicle for pro-imperial language and imagery which was more than merely symbolic. National events regularly shaped the way that people saw empire, and vice versa. The First World War of 1914-18 was one of the most prominent opportunities for widespread propaganda in support of the British Empire, as soldiers from across the colonies fought for Britain in an attempt to maintain her own vast empire and halt Germany’s imperial ambitions.

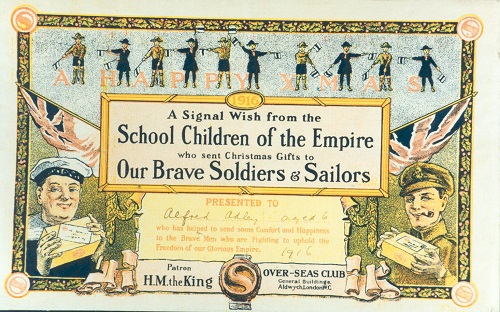

Copy of a framed certificate "A Happy Xmas 1916", "A signed wish from the school children of the Empire who sent Christmas gifts to our Brave Soldiers and Sailors. Presented to Alfred Adley, aged 6, who has helped to send some comfort and happiness to the Brave Men who are fighting to uphold the Freedom of our Glorious Empire".

Copy of a framed certificate "A Happy Xmas 1916", "A signed wish from the school children of the Empire who sent Christmas gifts to our Brave Soldiers and Sailors. Presented to Alfred Adley, aged 6, who has helped to send some comfort and happiness to the Brave Men who are fighting to uphold the Freedom of our Glorious Empire".

This framed certificate was issued to Thames Ditton schoolboy Alfred Adley in 1916, as a thank you for sending out Christmas gifts to men fighting for Britain in the First World War (1914-18). Interestingly, the certificate refers to the “school children of the Empire” and emphasises the “Freedom of our Glorious Empire”.

“In the patriotic mood of 1914… Jamaica’s terrible history of slavery, rebellion and repression was for the moment set aside and the descendants of the enslaved encouraged to imagine themselves members of an imaginary British Empire of sympathetic paternalism and racial equality.” David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History.

David Olusoga OBE is professor of Public History at the University of Manchester. He writes regularly for BBC History Magazine and The Guardian, and presents BBC history documentaries Black and British, and A House Through Time.

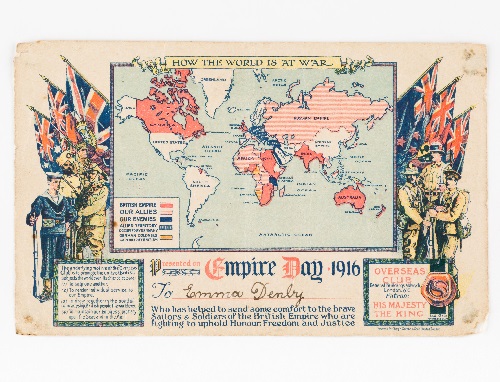

Certificate presented to school children who collected money for gifts to service men 1915/16. Presented to "Emma Denby" a scholar at School road School, Molesey. Presented on "Empire Day". 1916.

Certificate presented to school children who collected money for gifts to service men 1915/16. Presented to "Emma Denby" a scholar at School road School, Molesey. Presented on "Empire Day". 1916.

This certificate, much like the one above, was presented to schoolgirl Emma Denby, a scholar at School Road School in Molesey, for collecting money for gifts to service men in the First World War. It depicts the territories held by and fighting for the British Empire in dark pink, and portrays soldiers from some of these places around the edges of the map. It was presented on Britain’s ‘Empire Day’, an annual celebration of British Imperialism on the 24th May (now Commonwealth Day). Many historic British Pathé films shed light on the festivities of the day, including this one from 1914-18.

Britain went into the First World War to preserve its pre-eminence from the threat of European rivals, and marshalled the considerable human and natural resources of Empire to do so.” Kirsten Mckenzie, Britain: Ruling the Waves (Age of Empires).

Kirsten Mckenzie is Professor of History at the University of Sydney. She specialises in imperial history and the links between Britain and Australia, with publications including Imperial Underworld: An Escaped Convict and the Transformation of the British Colonial Order.

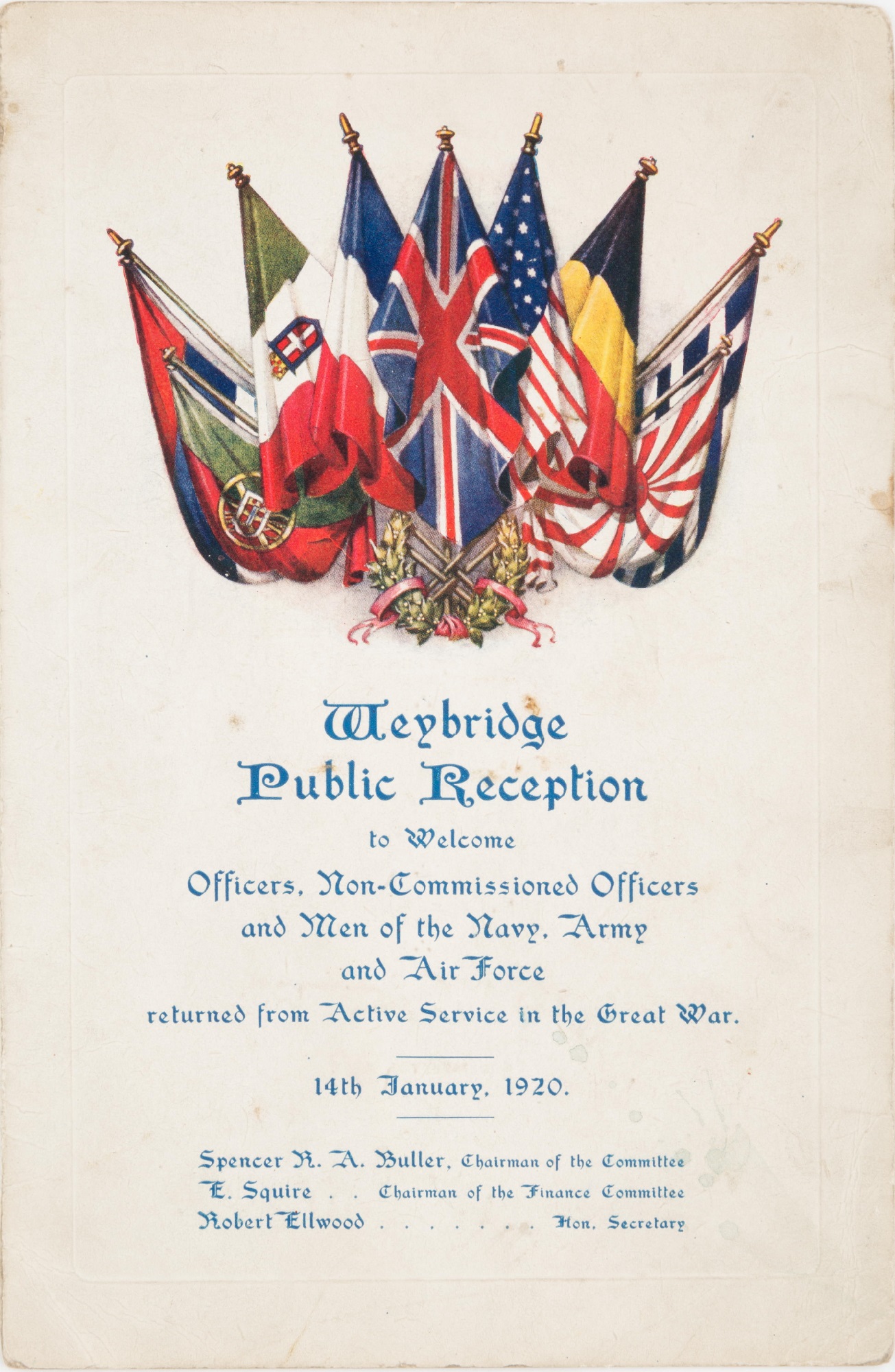

Programme for a Weybridge Public Reception dated 14th January 1914, to welcome men on active service in the Great War (1914-18). Nine flags are crossed at the top of the page, and details of the event are written in blue lettering on white card. Inside are details of the menu, programme, and the autographs collected.

Programme for a Weybridge Public Reception dated 14th January 1914, to welcome men on active service in the Great War (1914-18). Nine flags are crossed at the top of the page, and details of the event are written in blue lettering on white card. Inside are details of the menu, programme, and the autographs collected.

On the left is a menu from a Weybridge public reception held on the 14th January 1920, which welcomed officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the navy, army and air force returning from service in the First World War. The front of the menu depicts the flags of some allies to the British Empire, including the USA, France and Japan, but fails to specifically recognise the huge number of soldiers from British colonies who fought for the British Empire both on the Western Front and further afield.

“More than 100,000 Indians went to Flanders and France to fight on the Western Front… From 1911 onwards Indian soldiers had been eligible for the Victoria Cross – the highest award for gallantry in military service to the British crown… The first of them was won by Khudadad Khan Minhas, a sepoy (equivalent to private) infantryman who manned a machine gun at the First Battle of Ypres”. Dan Jones and Marina Amaral, The Colour Of Time.

Dan Jones is a historian, journalist, and presenter, best known for his work on medieval Britain and the Crusades including The Plantagenets, The Hollow Crown and a variety of Channel 5 documentaries.

Marina Amaral is an artist who specialises in digital colourisation of black and white images. She has collaborated with a number of museums and heritage institutions, including English Heritage and Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, and is the founder of the Faces of Auschwitz project.

Black and white photograph copy of a postcard of woman and six children in fancy dress representing British Empire. Pre-First World War.

Black and white photograph copy of a postcard of woman and six children in fancy dress representing British Empire. Pre-First World War.

This black and white photograph is a copy of a postcard showing a woman and six children in fancy dress representing the British Empire and its subjects. It was taken before the First World War began and demonstrates the acute awareness of British imperialism, as well as the pride and positive feeling British people had towards it from a young age thanks to propaganda and a pro-imperial education.

“Britons were submitted to generations of deliberate imperialist, militarist propaganda in all areas of culture, from education to the cinema, theatre and music halls and in the production of huge imperial exhibitions at Wembley and elsewhere.” Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire.

This is a postcard of a black and white photograph of King George V and Queen Mary visiting the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 in a state carriage. Amongst other aims, the official guide to the exhibition stated that it would find new sources of imperial wealth and demonstrate to Britain the possibilities in the Dominions and Colonies. 2,613 people and animals took part in this grand pageant, with the messages about imperial expansion endorsed by the royalty who attended and gave speeches there for the state opening.

“The willingness to accept imperial violence as a natural order remains perhaps the most disturbing factor in the whole of these barbaric celebrations of conquest.” Paul Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939.

Paul Greenhalgh is a historian of art and design. He was formerly head of research at the V&A Museum and is currently Director of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at the University of East Anglia. He has also published a number of books, including Ceramic, Art and Civilization.

Colour Poster of 'Her Majesty Queen Victoria and Empress of India'. From Penny Illustrated Paper, Jubilee Number June 1887.

Colour Poster of 'Her Majesty Queen Victoria and Empress of India'. From Penny Illustrated Paper, Jubilee Number June 1887.

This colour poster of ‘Her Majesty Queen Victoria and Empress of India’ is from the Penny Illustrated Paper’s Jubilee Number in June 1887. India is not a topic which might immediately come to mind when we think about Queen Victoria. Yet her title as ‘Empress of India’ is displayed proudly in most of her royal depictions. This title was taken very seriously by Victorian society, to the extent that it became a part of Victoria’s queenly identity. During her reign, Indians found themselves at the receiving end of huge amounts of British force. About 800,000 people were killed there during the Great Rebellion of 1857-8 against the British East India Company, due to violent British retaliation. This only came to an end when, in 1858, Queen Victoria established royal governance over India by forcing its people to submit to the British Raj. It is a subject popularly portrayed both then and now in propaganda, cartoons and films about Victoria’s rule.

“In the 1950s and 1960s we were brought up at home and school with rose-tinted spectacles about the British Empire… we were given a Raj drenched in nostalgia in novels, on television and in the cinema. But, however we dress it up, imperialism is still imperialism… The natural resources of India were plundered, and her people treated like children by those who saw themselves as the superior race.” Michael Wood, The Story of India.

Michael Wood is Professor of Public History at the University of Manchester. He is also a journalist and broadcaster, presenting over 100 history documentaries since the 1970s, including The Story of England, The Story of China and The Story of India.

Explore the bibliography for this section for some great further reading, or take a look at our exhibition booklist for some other excellent titles which can be found in your local Surrey Library branch.

Download the Exhibition Booklist at the bottom of the Objects of Empire homepage

Leave a comment

We'd love to hear your perspective on Empire in historic thought.You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register