Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

A final way in which the British Empire reveals itself is in Elmbridge’s landscape. Although not always obvious, the vast fortunes and wealth generated by individuals involved in activities across the British Empire was often invested in the landscape, establishing itself in the form of buildings, statues and monuments across the entire country - including our own borough.

Claremont House in Esher is one of the most prominent of these places, with the majority of the building which can be seen today built from the colonial wealth of Lord Robert Clive in the 18th Century. A ‘nabob’ of Britain’s East India Company, he amassed a fortune from his activities in India, aggressively expanding British-controlled territory across the country.

The strong bonds to empire in historic houses and monuments such as this one, as well as subtler links in places which have been influenced by or more casually connected to empire, are often ignored. Outlined below are a few of these places across Elmbridge which present themselves through objects, prints and photographs in our collection.

Black and white print of Queen Elizabeth I. Portrait showing a high ruff, in an oval medallion,. set in a square frame, outlined with leaves. The Royal coat of arms is at the bottom of the print. Across top words"Engraved For Harrison's Edition Of Rapin's History Of England. Elizabeth, Queen Of England, France And Ireland".

Black and white print of Queen Elizabeth I. Portrait showing a high ruff, in an oval medallion,. set in a square frame, outlined with leaves. The Royal coat of arms is at the bottom of the print. Across top words"Engraved For Harrison's Edition Of Rapin's History Of England. Elizabeth, Queen Of England, France And Ireland".

This black and white print of Queen Elizabeth I was “Engraved For Harrison’s Edition Of Rapin’s History Of England.”. Elizabeth appears in an oval medallion set in a square frame, with the Royal coat of arms at the bottom of the print. Many see Tudor England as an insular landscape which formed its own unique English identity. But, in reality, this was a time in which outside influences were strong, many people of African descent lived in the country, and the foundations for Empire were already being laid through the exploration of new international relationships and the goods which Africa had to offer. This would eventually come to influence our landscape – and the history books on our shelves.

“While Drake was at sea, Queen Elizabeth herself was seeking to cultivate relationships with Africa… Africans appeared critical to England’s survival in her existential struggle against the Catholic superpower that was Spain under Phillip II … Without understanding the presence and the impact of people of African descent it is impossible to fully understand the character and mindset of the Elizabethan age.” David Olusoga, Black and British.

David Olusoga OBE is professor of Public History at the University of Manchester. He writes regularly for BBC History Magazine and The Guardian, and presents BBC history documentaries Black and British, and A House Through Time.

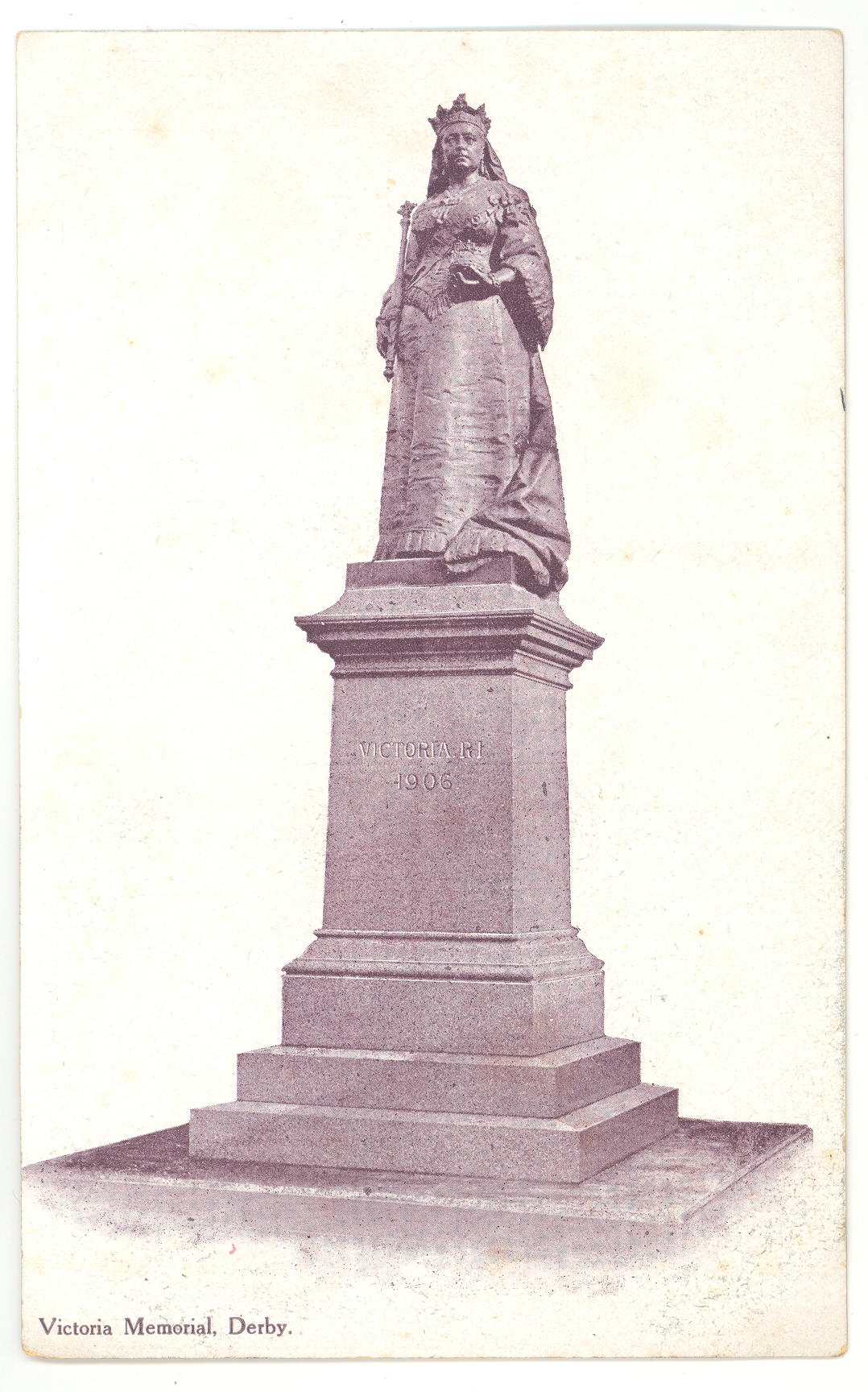

Sepia portrait postcard entitled Victoria Memorial, Derby. Queen Victoria with crown, orb and sceptre is standing on a stepped stone plinth with the text Victoria RI 1906. The memorial is thought to have been cast at the Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry.

Sepia portrait postcard entitled Victoria Memorial, Derby. Queen Victoria with crown, orb and sceptre is standing on a stepped stone plinth with the text Victoria RI 1906. The memorial is thought to have been cast at the Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry.

This sepia portrait postcard is entitled “Victoria Memorial, Derby.” In it Queen Victoria, with a crown, orb and sceptre, is standing on a stepped stone plinth with the text “Victoria R.I 1906”. R.I stands for Regina Imperatrix, meaning Queen Empress, and underlines Britain’s power over a vast Empire.

The memorial, like many others of Victoria, is thought to have been cast at the Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry. It is an example of how industry in Elmbridge had a hand in upholding images of Empire in the national landscape as well as reflecting Empire in its own landscape. In its years of operation from 1874—1976, the Foundry cast some of the most notorious bronze statues of the British Empire, including the ‘Peace Quadriga’ sculpture on top of the Wellington Arch in Hyde Park Corner.

“To decolonise is to add context that has been deliberately ignored and stripped away over generations. There are many examples of the misrepresentation of objects in museum displays that have only been corrected after dialogue with source communities. And there are countless instances where interpretation still needs to be rectified and stories freshly told.” Sharon Heal, Who’s Afraid of Decolonisation? (Museums Association).

Sharon Heal is Director of the Museums Association. She writes regularly about culture and museums, and is also a board member of the Museum of Homelessness.

This is a black and white photograph of Picton House, the former home of Cesar Picton (c.1755-1836). Cesar’s story reflects Britain’s exploitation of its expanding Empire to become heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade. Cesar was originally from Senegal, enslaved by the time he was six years old and bought as a present for Sir John Philipps, who lived at Norbiton Place near Kingston. Although he was not treated the same as enslaved people sent to work in Britain’s American colonies, Cesar was effectively forced to work as a servant. On the death of the Lord and Lady, he used the legacy of £100 left to him to become a successful merchant and settle in Thames Ditton. There is now a blue plaque on Picton House commemorating him.

“What does it say about this society that, after two centuries of being one of the most successful human traffickers in history, the only historical figure to emerge from this entire episode as a household name is a parliamentary abolitionist?” Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire.

This is a pen and ink sketch of Claremont from 1868, by the artist Robert Taylor Pritchett who lived in Esher. Claremont is one of the most prominent stately homes in Elmbridge’s landscape, and the building which can still be seen today has strong links to the British Empire. It was originally built for Lord Robert Clive of India, a hugely rich nabob of the British East India Company and one of the founders of Britain’s Indian Empire. He suppressed people across the country with the capture of new land and amassed a huge amount of money while doing so. Clive is reputed to have spent over £100,000 of his vast fortune on rebuilding the house and gardens. However, he died the year that the house was finished, in 1774.

“All over the English countryside, Palladian mansions were springing up, financed in many cases by the wealth obtained through British expansion into the Atlantic world and (increasingly) into India… If empire, by this time, was central to the domestic world of Britain itself, this did not preclude the judicious turning of a host of blind eyes… especially those who were using imperial wealth to climb the British social ladder, it was perhaps better not to see, not to know, not to hear.” Kirsten Mckenzie, Britain: Ruling the Waves (Age of Empires).

Kirsten Mckenzie is Professor of History at the University of Sydney. She specialises in imperial history and the links between Britain and Australia, with publications including Imperial Underworld: An Escaped Convict and the Transformation of the British Colonial Order.

King George V and Queen Mary, flanked by A. B. Burton (right) and Sir Thomas Brock, in Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry during the Royal visit of 1921. The statue of Edward VII was sent to New Delhi.

King George V and Queen Mary, flanked by A. B. Burton (right) and Sir Thomas Brock, in Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry during the Royal visit of 1921. The statue of Edward VII was sent to New Delhi.

This picture shows King George V and Queen Mary, flanked by A. B. Burton (right) and Sir Thomas Brock, in Thames Ditton Bronze Foundry during the Royal visit of 1921.

The statue of the late Edward VII behind them was sent to New Delhi, the capital of the British Raj, the royal imagery acting as a visible symbol of British ascendency there. It was taken down in 1947 and sent to Toronto, Canada, in 1969, where it still stands.

“By the 1830s the [East India] Company archives shift from trade in textiles to ownership of land, and at this point the colonial project acquires a new ideological tone… British dominion in India was not only to be about making money, but about changing India.” Michael Wood, The Story of India.

Michael Wood is Professor of Public History at the University of Manchester. He is also a journalist and broadcaster, presenting over 100 history documentaries since the 1970s, including The Story of England, The Story of China and The Story of India.

Photograph of the Memorial to William Whiteley taken in 1983. The memorial stands in the centre of the octagon at Whiteley Village on a pavement with grass around.

Photograph of the Memorial to William Whiteley taken in 1983. The memorial stands in the centre of the octagon at Whiteley Village on a pavement with grass around.

This is a photograph of the memorial to William Whiteley, which stands in the centre of the octagon at Whiteley Village on a pavement with grass surrounding it. The life story of William Whiteley is told in the inscription on the south side of the Central monument. Born at Agbrigg in Yorkshire, in 1831, he was apprenticed at the age of 16 to a drapery firm in Wakefield. He went to London to see the Great Exhibition of 1851, and was inspired by the array of exhibits there from across the British Empire. He started a small business of his own, William Whiteley Limited, which eventually became Whiteleys, one of the first department stores in London. This included a fashionable ‘Oriental Department’, which made use of Britain’s imperial influence over trade with China by stocking cheap imports from the country. Whiteley died in London on the 24th January, 1907, leaving £1 million of his huge fortune in his will to build Whiteley retirement village in Elmbridge.

“The First Opium War was fought between 1839 and 1842; in 1856 a second began. These wars pitted the naval might of the British Empire and its French allies against the Qing, and drew in many other issues of contention between the powers, including general rights of free trade with China… [in October 1860] the British looted the city’s Yuan Ming Yuan (Old Summer Palace) of its priceless porcelain treasures, and then burned it. The humiliated emperor fled and a punitive treaty was imposed, highly favourable to Britain and France.” Dan Jones and Marina Amaral, The Colour Of Time.

Dan Jones is a historian, journalist, and presenter, best known for his work on medieval Britain and the Crusades including The Plantagenets, The Hollow Crown and a variety of Channel 5 documentaries.

Marina Amaral is an artist who specialises in digital colourisation of black and white images. She has collaborated with a number of museums and heritage institutions, including English Heritage and Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, and is the founder of the Faces of Auschwitz project.

Michael Sassoon, Siegfried Sassoon (the First World War poet) and Hamo Sassoon as children, with Alfred Ezra (b.1861, d.1895), the son of Sassoon David Sassoon, photographed in 1894.

A photograph of the outside of Ashley Park House, Walton-on-Thames, taken in the early 1900s when it was home to the Sassoon family.

The seven children of Joseph and Louise Sassoon photographed outside Ashley Park c. 1897. They are (left-right) Mozelle, Missy, Freddy, Arthur, Totts, Teddy and David.

Pictured to the left are various Sassoon family photographs taken at Ashley Park. The Sassoon family moved to Walton after David Sassoon purchased the Ashley Park Estate in the 1860s. David Sassoon was born in Bombay, then under British control, in 1832. He was part of a huge trading family, and his father (also David) had amassed wealth through his involvement in the opium and cotton trades. David Sassoon continued this tradition, and later used his wealth to move to England with his wife, settling at the luxurious Ashley Park in Walton. The estate and house were sold for re-development in 1923. Subsequently, the house was demolished and the grounds built over.

“The opium was produced in British India and was smuggled into China by (mainly) British merchants. Beijing had prohibited the import, cultivation and smoking of opium since 1800, as it was well aware that the drug was doing tremendous damage to its economy as well as to the population.” Jung Chang, Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China.

Jung Chang is a writer and historian. She has published a number of books on modern China, including Mao: The Unknown Story. Her 1991 historical autobiography Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China sold over 10 million copies worldwide.

A black and white photograph of 20 Monument Green, taken in 1982—roughly 50 years after author E.M Forster's occupation of it in the 1920s.

A black and white photograph of 20 Monument Green, taken in 1982—roughly 50 years after author E.M Forster's occupation of it in the 1920s.

It is here at 20 Monument Green, in Weybridge, that E.M. Forster wrote one of his most famous books in the 1920s. ‘A Passage To India’, was heavily influenced by the British Empire in India. Parts of the novel reinforced the idea that it was natural for Britain to take control of Indian politics, although Forster does also present many aspects of British colonialism as flawed. One of the main themes underscoring the book is the tension between India and its colonisers, making it controversial at the time it was published in 1924.

‘ “I’m going to argue, and indeed dictate,” she said, clinking her rings. “The English are out here to be pleasant.”

“How do you make that out, mother?” he asked, speaking gently again, for he was ashamed of his irritability.

“Because India is part of the earth. And God has put us on earth in order to be pleasant to each other. God… is… love.” She hesitated, seeing how much he disliked the argument, but something made her go on. “God has put us on earth to love our neighbors and to show it, and he is omnipresent, even in India, to see how we are succeeding.”‘ E.M. Forster, A Passage to India.

Edward Morgan Forster (1879-1970) was a British author and critic. His work often examines the themes of class, colonialism, sexism and social injustice. As well as A Passage to India (1924), he is famous for the novels A Room With a View (1908) and Howards End (1910), both of which have been portrayed in film.

Explore the bibliography for this section for some great further reading, or take a look at our exhibition booklist for some other excellent titles which can be found in your local Surrey Library branch.

Download the Exhibition Booklist at the bottom of the Objects of Empire homepage

Leave a comment

Let us know your thoughts on Empire in Elmbridge's historic landscape.You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register