Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Animals, aside from being useful commodities to some, have also always fascinated us. In some cultures, various animal species are considered holy. From the earliest cave paintings to the most up-to-date contemporary art, the depiction of animals and what they mean to humans and society has always been a mainstay of visual culture.

The branch of science concerned with classification, especially of organisms; systematics.

The art of preparing, stuffing and mounting the skins of animals with lifelike effect. In Greek, ‘Taxis’ means arrangement and ‘Derma’ means skin.

Someone who practises taxidermy.

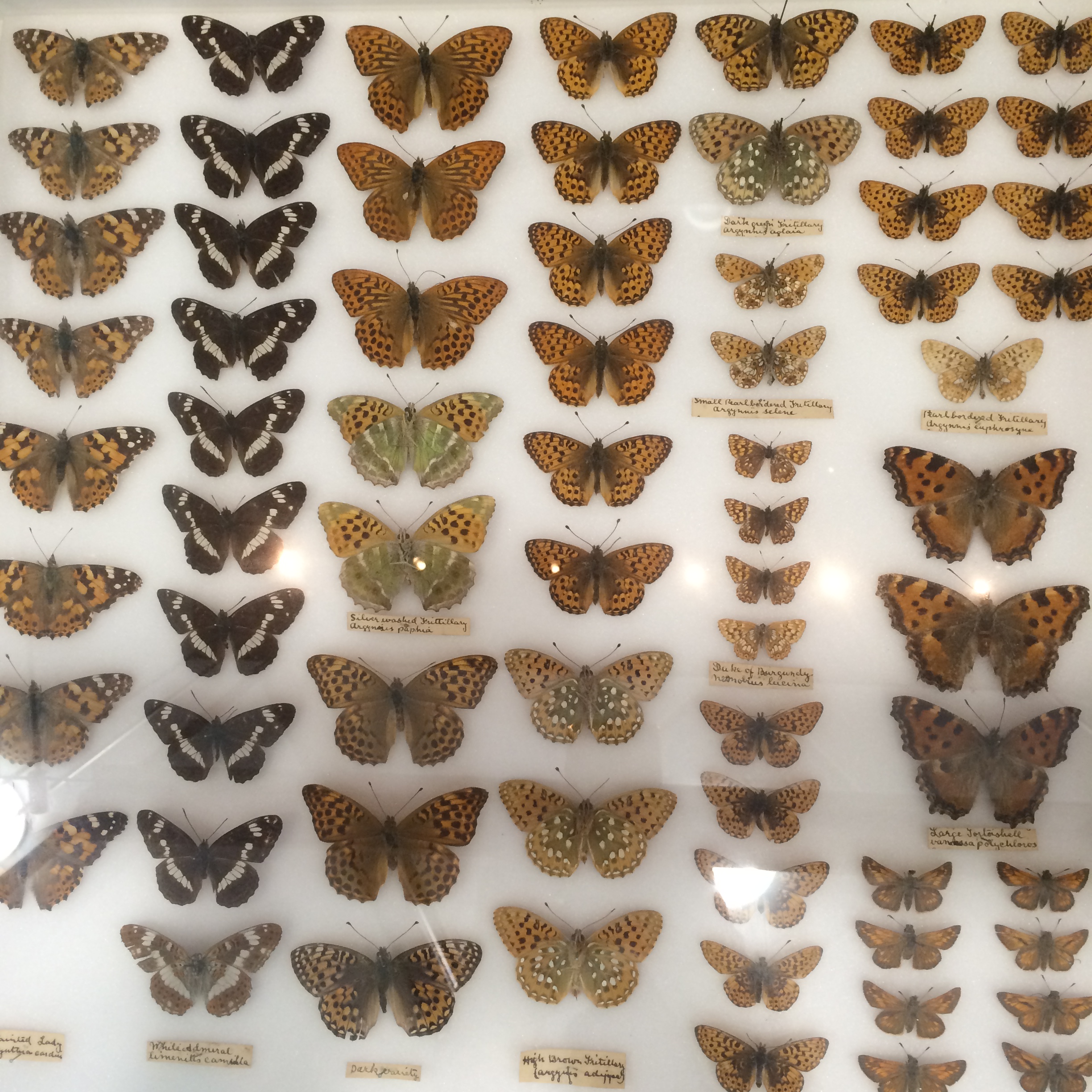

Wooden display cases of moths & butterflies, collected from the Claygate area by Edward James Smith, c.1894-7.

The history of preserving the natural world is an old one: mummification is one of the oldest forms of preservation. From the 16th century onwards, wunderkammer – ‘cabinets of curiosities’, rooms full of exotic and wonderful artifacts – were constructed by wealthy individuals to display their knowledge of – and power over – the world. Although the boundaries of classification would be imposed later, the cabinets included natural history objects (both real and fake), archaeological finds, and historical relics. The contents of some of these cabinets informed museum collections around the world.

With the 18th and 19th century’s investigations into natural science, individuals became obsessed with natural history. The display of nature was not limited to the museum; naturalists would mount displays in their homes or on their person in the form of hats and skins.

This online exhibition explores some timeless themes relating to animals through objects from the Elmbridge Museum collections. Starting from beautifully mounted butterflies, a practice that categorises nature, a dual narrative can be formed – one leading into the museum, the other into the home.

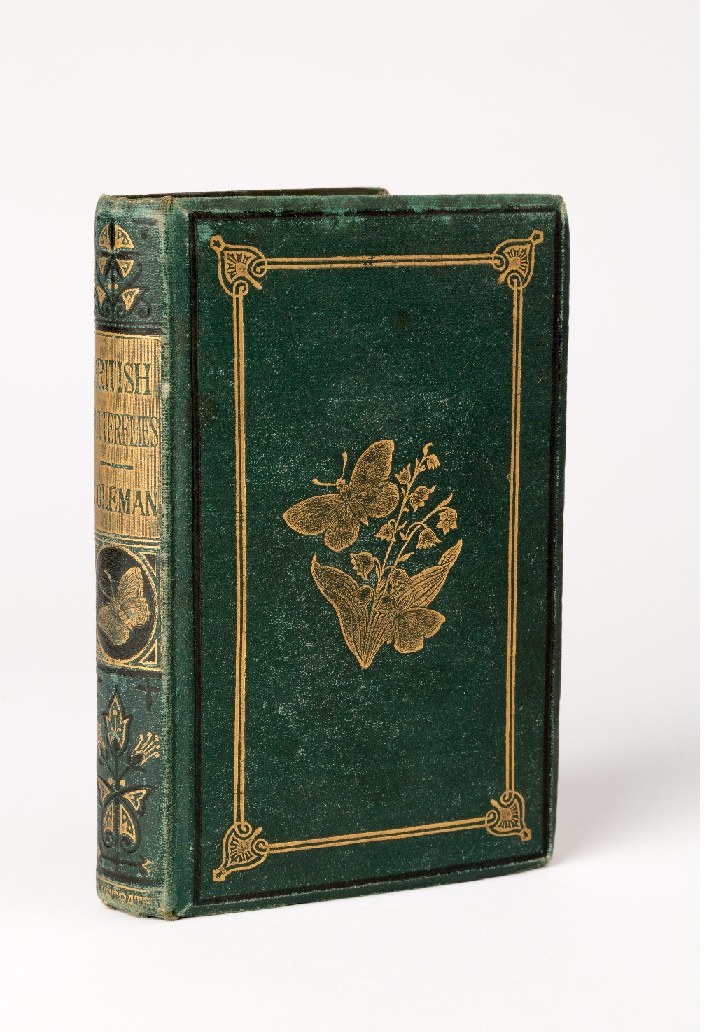

‘British Butterflies’ by William Coleman. From a collection of five butterfly and moth reference books owned by Edward James Smith, a Claygate collector.

Noah, and his mission of gathering pairs of animals, has been credited with being the first attempt to fully categorise the natural world. Stemming from this first instance, ideas of classification and identification have continued.

Butterfly collecting was much more popular in Britain during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries than it is now. However, it still remains a fashionable hobby in other parts of the world such as Japan. The Large Tortoiseshell butterfly was a common species until the 1940s, but there have been hardly any sightings since 1953 and it was declared extinct in the 1980s. Common domestic hobbies, such as butterfly collecting and mounting, illustrate tendencies that can be traced back to Noah and his ark but the stark realisation that such plentiful creatures – ones that hobbyists once brought into their homes – are now extinct, is jarring.

The relationship between practices such as butterfly collecting and flower pressing are interesting because they were informed by traditional museum practices, but they also informed them in return.

In the archive, Elmbridge Museum has box upon box, carefully stacked and encased in protective wrapping. Take a peek inside them, and you will find rows of meticulously arranged butterflies, from tiny Common Blues to larger Red Admirals. More than 100 years ago, Claygate local Edward J. Smith collected each and every one of these specimens from our local area, painstakingly arranging them by hand into the beautiful array that we can still see today.

Unlike the sad case of the Large Tortoiseshell butterfly, not all animals struggle against the expansion of human interaction into traditional natural habitats; the kestrel is an example of one such animal. Kestrel numbers have remained steady despite large expansions of towns and cities into green spaces. Kestrels can often be seen hovering over motorways or perched atop electricity pylons.

Other birds have been less fortunate. The hen harrier, native to many parts of the UK, is one of the country’s most persecuted birds of prey. Hen harriers are targeted because they reduce the number of grouse available to shoot – they have become victims of a very modern conflict between man and animal.

Hundreds of years ago, Elmbridge was home to numerous species of uncommon birds, and contained a treasure trove of different flying insects. The Lapwing, a wetland bird which makes its nest on the ground, is incredibly rare because of its susceptibility to predators.

The displays below are typical full-body cabinet displays of taxidermy, where the whole animal is preserved and arranged in a natural pose.

This Noah’s Ark, because it is a toy, is located squarely in the home environment but with animals that, in 1910, would have been seen as ‘exotic’. The opening of London Zoo in 1828 started a craze for depicting ‘exotic’ animals in toys and illustrated books; Montgomery the Monkey shows us this was true in the local area. London Zoo also gave us, in the form of an incredibly large elephant, the term ‘jumbo’ that is still in use to this day.

Stuffed ‘Montgomery the Monkey’ toy, 1920.

Noah’s Ark and Animals wooden toy, c.1910.

The process of taxidermy, in this exhibition at least, holds a strange place that straddles both the extraordinary and the banal. Kestrels, for example, are very common birds, yet the Maltese Terrier, through its royal provenance, is a one off specimen. Pets are one way in which animals have been bought into the domestic setting; however, by mounting it in an elaborate way under a dome, the Duchess of Wellington’s terrier looks more like a museum artefact.

The final objects in this exhibition illustrate the conclusion of the two narratives that have been running from the mounted butterflies through to now: one toward the domestic, the other toward the museum.

The mounted birds from further up the page provide fine examples of traditional museum displays of taxidermy.

Juxtaposing a mounted bird with a children’s toy of the same animal exhibits a modern tendency to invite animal imagery into the home while distancing ourselves from the real thing. The most troubling aspect of this relationship is the fact that the toy chicken is caged. The chicken coop, just like the glass fronted taxidermy and butterfly cases, shows how humans have always (and probably always will) pen animals, whether in categories of classification or cages.

Take a look at our handy guide to historic birds in our borough!

Discover more prominent animals in Elmbridge's past in our A Day at the Races online exhibition, where we delve into the eventful history of Sandown and Hurst Park racecourses, from the first races, over hurdles and ending in the present day.

Go to the A Day at the Races online exhibition

Leave a comment

Let us know your thoughts on Elmbridge Museum's historic taxidermy collections!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register