Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Much has been discussed about identity and self-identification these days. How you see yourself, and how others perceive you, has a role in shaping our social experiences and in how we connect and interact with the world around us.

More and more societies are becoming aware of the importance of identity and the debates around it, be it racial, gender, political or regional identities. But identity also played an important part in 17th century English politics. Have you ever wondered why the Diggers were called “the Diggers”? How this came to be the group’s name and what it meant? In this blog, we answer some of these questions.

A common motif in 16th and 17th century political and religious debates, encompassing discussions about liberty, property and community, drawing back to the Anabaptists in the German Peasant’s Revolt in the 16th century. Putting it simply, the community of goods theory entailed – amongst other things – the abolition of private ownership of property.

The act of converting common land into private property through, for example, the marking of land with fences, changing the organisation and landscape of the countryside. In the 17th century, many places that used to be common land (to be used by all the inhabitants of the parish) were enclosed and had such communal status revoked.

A political movement that emerged between the end of the First Civil War (1642-1646) and the Second Civil War (1648-1649). The Levellers had sided with parliament during the conflicts but defended a series of stances that they believed were not being addressed by their new government, such as religious toleration, the expansion of male suffrage, and equality before the law.

They published various pamphlets and petitions disclosing their views. Their main members were John Lilburne, William Walwyn and Richard Overton.

Political activist who, during the Civil Wars, sided with parliament and was a member of the New Model Army. From 1645 onwards, however, Lilburne had more and more disagreements with parliament, being a fierce defender of religious tolerance and what he considered to be the inherent rights of Englishmen, such as equality before the law and extended male suffrage.

He led the Leveller movement and published a series of pamphlets sharing his perspectives, being prosecuted at various times by Oliver Cromwell’s regime. This even led to Lilburne living in exile in the Netherlands between 1652 and 1653. He died in 1657.

Shot of Diggers in the distance, from the 1975 film 'Winstanley'

Shot of Diggers in the distance, from the 1975 film 'Winstanley'

In our last post, we concluded by mentioning the aftermath of the occupation of St George’s Hill in April 1649: a report sent from John Bradshaw to Lord Fairfax warning him about what was going on. Now, we are going to take a deeper look at the many reactions the occupation sparked amongst various individuals and groups.

In Bradshaw’s report, we can already identify how he simultaneously tried to dismiss the Diggers as ‘ridiculous’ people, whilst still identifying in them a potential threat to the ‘peace and quiet of the Commonwealth’ (Bradshaw, 1649). Such a dismissive yet, at the same time, concerned tone would carry on being present in many of the comments about the group. In a report by Captain John Gladman, who was sent by Lord Fairfax to assess the situation, he even expressed that ‘[…] the business is not worth the writing nor yet taking notice of: I wonder the Council of State should be so abused with informations…’ (Gladman, 1649).

Nevertheless, the events on St George’s Hill clearly drew attention, as many newsbooks (the equivalent to modern day newspapers) covered the matter. When Fairfax finally rode to meet the people occupying St George’s Hill, a report of it was vehiculated in a pamphlet titled ‘The Speeches of the Lord General Fairfax, And the Officers of the Army to The Diggers at St. George’s Hill in Surrey, and the Diggers several Answers and Replies thereunto’ (1649).

It is interesting to note that, despite covering many other unrelated events, on the cover sheet of the pamphlet the main headline that figured in bold capital letters was that concerning the meeting of Fairfax with the Diggers. This could be evidence of the level of interest which had sprung up for the group amidst the London press!

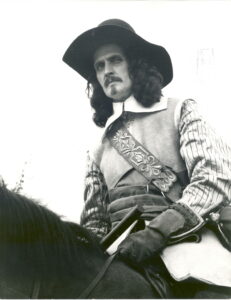

General Fairfax in the 1975 film ‘Winstanley’.

Many newsbooks wrote about the Diggers in some aspect, directly or indirectly. These approached the conflicts from different perspectives: the newsbook ‘The Moderate’ was associated with the Levellers, whilst ‘Mercurius Pragmaticus’ was royalist, and ‘Mercurius Brittanicus’ was republican, to cite just a few examples.

The ambiguity identified in Bradshaw’s report could be perceived in these coverages as well. ‘Mercurius Pragmaticus’ (17-24 April 1649) mocked William Everard and his ‘intention to convert Oatlands Park into a Wilderness, and preach Liberty to the oppressed Deer’, while warning that ‘what this fanatical insurrection may grow unto, cannot be conceived; for Mahomet had as small, and as despicable a beginning’ (Mercurius Pragmaticus cited by Gurney, 2007, p. 122).

Similarly, the newsbook ‘A Perfect Summary of an Exact Dyarie of Some Passages of Parliament’ (16-23 April 1649) appealed to their apparent ignorance: ‘they thought because they [the lands] were called commons, they belonged to anybody, not considering that they are the commons only for the inhabitants of such, or such a place: they are a distracted, crack brained people that were the chief’ (A Perfect Summary cited by Gurney, 2007, p. 123). This similar approach can be identified in many other newsbooks that reported on the group.

Black and white photograph of the wrecked huts in the 1975 film 'Winstanley', showing Miles Halliwell on the left, sitting down and Phil Oliver playing the characters of Winstanley and Everard.

Black and white photograph of the wrecked huts in the 1975 film 'Winstanley', showing Miles Halliwell on the left, sitting down and Phil Oliver playing the characters of Winstanley and Everard.

The combination of fear and dismissiveness characterising the general reactions to the St. George’s Hill group seemed to have sprung from the anxious assimilations that many people established between the group’s actions and enclosure riots from the beginning of the 17th century (Cavaillé, 2016).

Most poignantly, any attempt at debates that seemed to call into question the matter of private property appeared to be met with tremendous anxiety in this context in England. Even in cases where topics such as equality and liberty, for example, were being debated without calling the matter of property into question, if the language employed was perceived as having the potential to encompass any sort of criticism about the right to property, these were likely met with great resistance.

![‘The True Levellers Standard Advanced’, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, E.552[5].](https://elmbridgemuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/folha-de-rosto-213x300.jpg)

‘The True Levellers Standard Advanced’, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, E.552[5].

If the Levellers were already struggling in dissociating themselves from the idea of levelling men’s estates, with the appearance of Winstanley and his group and the reprint of the pamphlet ‘A Declaration to the Powers of England’ (Everard et al., 1649a) with a new added title, ‘The True Levellers Standard Advanced’ (Everard et al., 1649b), this struggle was rendered even more arduous. There is some debate concerning the choice of such a title: for decades, many historians interpreted this as a provocation on the part of Everard, Winstanley and their companions, of the group Lilburne was associated with, the Levellers: as if they were presenting themselves as being the ‘true’, the ‘real’ levellers, due to the nature of their programme, one which addressed the matter of abolishing private ownership of land. This interpretation gained so much power, that on the monument erected in the memory of Gerrard Winstanley in Weybridge, the words are as follows: ‘Worke together. Eat bread together. Gerrard Winstanley A True Leveller 1649’.

Gerrard Wisntanley Memorial Stone, Weybridge. Source: Photo taken by the author on 22 May 2021.

Gerrard Wisntanley Memorial Stone, Weybridge. Source: Photo taken by the author on 22 May 2021.

However, more recently some historians have questioned such interpretation. Ariel Hessayon, for example, argues that by ‘true leveller’ they meant Jesus Christ (Hessayon, 2008, p. 6), a way of referring to God and/or Christ that was somewhat current in 17th century radical politics. Indeed, in the pamphlet ‘A New-yeers Gift to the Parliament and the Armie’, the Diggers call Jesus Christ ‘the greatest, first, and truest Leveller’ (1650, p. 140), but they also mention that ‘true Levelling’ is directly connected to enjoying the land commonly (1650, p. 140; 144-145).

Nevertheless, as noted by Hessayon himself, the association between the St. George’s Hill group with ‘Leveller’, or yet with ‘new’ or ‘true’ Levellers, seemed to have stuck in the minds of their contemporaries (Hessayon, 2008, p. 7). We can assess this from various sources that established such connections. Some went as far as relating the occupation of St. George’s Hill to John Lilburne himself (imagine the confusion!) as was the case of the following report from the antiquarian John Aubrey, brought to us by Hessayon.

'[…] when visiting Surrey in 1673, the antiquarian John Aubrey incorrectly noted that St. George’s Hill was where ‘a great meeting of Levellers’ were ‘like to have turned the world upside downe,’ adding that they were ‘encouraged’ by their leader John Lilburne.' (Hessayon, 2008, p. 7).

We might never be completely sure about the group’s intentions with the adoption of ‘true levellers’ on the cover sheet of their pamphlet. But be it only a reference to God or an attempt to make a statement about themselves as opposed to Lilburne’s group, one thing is certain: from 1649 onwards, ‘levellers’, ‘true levellers’ and ‘new levellers’ started to meddle with the imagery and the perceptions that people were constructing about the group occupying St. George’s Hill. However, as aforementioned, Lilburne, his companions and his supporters, opposed any such associations between the groups. So, they proceeded to try to distance and dissociate themselves, not only from debates concerning property, but from what Winstanley and Everard were carrying out on St. George’s Hill.

In order to carry on with such differentiation before the public, an interesting approach was adopted on the part of Lilburne and his companions. Instead of endorsing that, yes, those on top of St. George’s Hill were indeed ‘levellers’ while they were not, they choose to pursue a complete dissociation from anything that could relate back to them. Hence resorting to labelling Winstanley’s group as ‘diggers’ in the Leveller-inclined newsbook The Moderate, in the publication of 17-24th April 1649.

In order to understand the choice of ‘digger’ to characterise the group pejoratively, we must look into the meanings that this word carried in 17th century England: it mainly made reference to simple, ignorant rural workers, as well as radical enclosure rioters, with no regard or respect for the concept of property and order, who had nothing to do with what ‘An Agreement of the People’ was standing for. The trend of referring to the group as diggers stuck, and the various London newsbooks that reported on them started to call them diggers, always with a pejorative connotation.

The labelling of the St. George’s Hill group as diggers seemed, then, to serve three main purposes: first, to dissociate them from the Levellers; second, to dismiss their cause altogether by representing them as nothing but simple, ignorant people; and third, to portray them as a threat by approximation with the enclosure riots of 1607.

![‘A Vindication of those, Whose endeavours is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called Diggers’, Gerrard Winstanley, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, C124h1[1]. ‘A Vindication of those, Whose endeavours is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called Diggers’, Gerrard Winstanley, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, C124h1[1].](https://elmbridgemuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Captura-de-Tela-2021-05-28-as-12.25.41.png) ‘A Vindication of those, Whose endeavours is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called Diggers’, Gerrard Winstanley, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, C124h1[1].

‘A Vindication of those, Whose endeavours is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called Diggers’, Gerrard Winstanley, 1649. Source: Copy of the original in the British Library, Thomason Tracts, C124h1[1].

An interesting turn to this narrative, however, would come in early June 1649, when Winstanley and his group published the pamphlet ‘A Declaration of the bloudie and unchristian acting of William Star and John Taylor of Walton, with divers men in womens apparel, in opposition to those that dig upon St. George Hill in Surrey’. In this pamphlet, they refer to themselves as diggers for the first time. From this point on, the name ‘Digger’ would progressively start to make its way into the cover sheets of the group’s pamphlets, being gradually employed with capital letters, and finally appearing in very bold letters at the very centre of the cover sheets of their pamphlets – as was the case in the pamphlet ‘A Vindication of those, Whose endeavors is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called DIGGERS’, from 1649 (Winstanley, 1649).

Differently from the Levellers, though, they didn’t make use of the term to attract attention whilst simultaneously trying to allege the injustice of it being used to label them – even if they did often note that they were ‘called’ diggers, emphasizing that this was a name attributed to them. But slowly, the Diggers seemed to progressively embrace this label, promoting a deep reappropriation of its meaning, one that encompassed representing themselves as ‘the poor oppressed people of England’, ‘the saints of God’, those fighting for the injustice of enclosures and of the buying and selling of the land. This built a powerful collective representation that, in their view, legitimized them to speak on behalf of all those being affected by the avoidance of such matters by the government of the Commonwealth.

In order to understand this turn, think for a minute about the SlutWalk movement that spread across many countries in the 2010s. It all began in Toronto, Canada, when in 2011, a police officer suggested that if women didn’t dress like ‘sluts’, they wouldn’t be raped (SlutWalk Toronto, 2019). The absurdity of the allegation – blaming the victim for being raped – sparked protests across many countries, with women denouncing the persistence of rape culture and questioning what it meant to dress or act as a ‘slut’: did it mean wearing and doing whatever they wanted? If so, then they claimed that they were all ‘sluts’, and that nothing justifies rape. Following the spark of the protests, feminist movements from all over the globe promoted a deep reappropriation of the once insulting term, claiming on many occasions that ‘if to be free is to be a slut, then we are all sluts’. Nowadays, within the feminist movement and even feminist pop culture, slut is a term much more associated with the SlutWalk movement than with a pejorative, patriarchal labelling of women.

Of course, such comparisons and approximations must be done with extreme caution, but in a way, what the Diggers did was a little bit similar. They appropriated a term used to dismiss and ridicule them, and transformed it into a source of legitimacy, of empowerment and collectiveness – they believed and claimed, after all, to be speaking on behalf of all the poor oppressed people of England. Thus, identity disputes and formation were also an important element of seventeenth century politics.

In our next post, we move on to how the inhabitants of the local communities reacted to the Diggers’ occupation of St George’s Hill.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to hear your thoughts!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register