Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Perhaps the most remembered and mysticised event related to Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers was the occupation of St. George’s Hill in April 1649.

In recent decades, it has become both a symbol and an inspiration for various movements centralised around the matter of land and property. But what was really happening on St. George’s Hill in April 1649?

In the field of History, to think of something anachronistically is to think about it out of its proper date and context, hence making erroneous considerations and analysis about it.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines anachronism as ‘an error in computing time, or fixing dates; the erroneous reference of an event, circumstance, or custom to a wrong date’, and ‘anything done or existing out of date; hence anything which was proper to a former age, but is, or, if it existed, would be, out of harmony with the present’ (‘Anachronism, n.’ OED Online. Oxford University Press, March 2021. Access: 7 May 2021).

A strategy within political activism that entails taking specific actions (that can be either violent or non-violent) in order to achieve goals, demonstrate the existence of a problem, attract the attention of the public and/or the authorities to a specific matter, and push for change or solutions of some sort. Workers’ strikes, boycotts, occupations, hunger strikes, sit-ins and politically oriented property destruction are all examples of direct action.

The act of converting common land into private property through the marking of land with fences, changing the organisation and landscape of the countryside. In the 17th century, many places in England that used to be common land, to be used by all the inhabitants of the parish, were enclosed and had such communal status revoked. This was something deeply opposed by the Diggers.

Compulsory provision of board and lodging to soldiers during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

An army assembled by the English Parliament in 1645 to fight against King Charles I during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was a professional army, where soldiers were employed full-time by parliament, different from the militias that were usually employed by English kings until then, since England did not have a permanent standing army. It was disbanded in 1660 with the Restoration of king Charles II to the thrones of England and Scotland.

The Norman Yoke was a theme frequently explored in discourses from a variety of subjects in 17th century England. It recalled the Norman Conquest of 1066, when William Duke of Normandy successfully invaded and conquered England, but in a very negative way.

Individuals often placed the beginning of the various grievances that affected England (which would change depending on the perspectives fostered by each group or individual) to the invasion by the Normans and the consequent rearrangements to English society and government that were imposed by them. This also entailed an idealisation of the “Saxon golden age”, with Edward the Confessor and Alfred the Great figuring like ‘ideal’ monarchs. In the 17th century, it was current for groups such as the Diggers and the Levellers to characterise members of the nobility and the gentry as descendants from the Normans, and hence, oppressors.

Those who occupy land or property such as houses or flats that don’t legally belong to them.

This was a document developed by the Parliament in 1641, which configurated an oath of allegiance to be taken by all those over 18 years of age, to defend the constitution and the Church of England. It was an attempt to try to ease tensions between king and parliament and avoid a war. However, as we know, this failed, and tensions continued to rise until August 1642 when the Wars started.

Firstly, it is important we understand how the Diggers ended up digging at St. George’s Hill – how they paved the ‘road to George Hill’, as put by Thomas Corns (2006, p. 185).

As seen in our first post, Winstanley was another bankrupt Englishman forced to move out of London to the countryside and begin a series of failed attempts to get back on his feet. The disrupted context his country was in, alongside the tumultuous path he had been going down in his personal life, had driven him to write about God and religion, and what he perceived to be the injustices that plagued England in the 17th century. Although religion had been the focus of his very first pamphlets, social, political, moral and economical criticism had begun to gain more and more space on his pages. Not only that, but he started connecting with people who had experienced similar hardships, people like William Everard, who had been in the New Model Army fighting for Parliament and was finding himself disappointed by the government he had helped to bring to power.

Winstanley himself reinforced on several occasions in his pamphlets that yes, he opposed the ‘devilish’ monarchy of Charles I, that ‘pharaoh’ who kept his people under the tight grasp of kingly oppression, and even if in a rather discreet way, he had come to voice his (not unconditional) support for the parliamentarian cause of overthrowing the monarchy (Winstanley, 1648, p. 166). But this did not stop him from also criticising Cromwell and his Commonwealth, especially so after they came to power. One crucial point for Winstanley in his criticism of parliament after the 1649 regicide, was concerned with law reform: he argued that it was not enough to get rid of the king without changing the laws that governed England, for these carried on maintaining society in an oppressive arrangement, where the few were entitled to much and the many were entitled to practically nothing. In a nutshell, Winstanley believed that a greater structural change should take place in England, and they were starting to see Cromwell and his regime more in terms of continuity with the many faults of the monarchy, rather than the change they had been wishing for.

In the pamphlet ‘An Appeal to the House of Commons’, published in 1649, we can see how Winstanley argued that he, alongside his companions, contributed to the parliamentarian cause through the payment of taxes. In his view, this meant that parliament owed them the freedom promised, and such freedom, for the Diggers, was directly connected with being able to freely enjoy the land:

'…they were incouraged to arrest us upon your Act of Parliament (as they tell us) to maintain the old Laws; we desired to plead our own cause, the Court denied us, and to fee a Lawyer we cannot, for divers reasons, as we may show hereafter. […] Whether the common people, after all their taxes, free-quarter, and loss of blood to recover England from under the Norman yoke shal have the freedom to improve the Commons, and waste Lands free to themselves, as freely their own, as the Inclosures are the propriety of the elder brothers? Or whether the Lords of Manors shall have them, according to their old Custom from the Kings Will and Grant, and so remain Task-Masters still over us, which was the peoples slavery under Conquest.' (p.66-67)

As we have seen, Winstanley’s first five pamphlets were mainly concerned with the development of his religious views. Through these, he established his belief in the equality of all mankind, and that God should be found within, and not in ‘false preachers’. Winstanley even defended a far more metaphorical interpretation of biblical passages, arguing that the Bible should be handled as a careful source of God’s words, since it was written by men.

It was in his pamphlet ‘The New Law of Righteousness’, published at the beginning of 1649, that Winstanley developed and asserted his social views in a more detailed way, after describing the vision that had been sent to him by God telling him to ‘work together, eat bread together‘ and ‘declare this all abroad’ (Winstanley, 1649c, 513). In this pamphlet, matters regarding the land started to gain more centrality, yet no mention of occupying land, nor urges to act, were made in his work up until this point. Sometime after the publication of this last ‘solo’ pamphlet, however, Winstanley got involved with the Diggers, and within a few months would be alongside Everard and others occupying St. George’s Hill. In the pamphlet ‘A Watch-Word to the City of London and the Army’, published later in 1649, Winstanley had this to say about the period following the publication of The New Law of Righteousness:

'I came, then I was made to write a little book called, The New Law of Righteousness, and therein I declared it; yet my mind was not at rest, because nothing was acted, and thoughts run in me, that words and writings were all nothing, and must die, for action is the life of all, and if thou dost not act, thou dost nothing. Within a little time I was made obedient to the word in that particular likewise; for I took my spade and went and broke the ground upon George-hill in Surrey, thereby declaring freedom to the Creation, and that the earth must be set free from entanglements of Lords and Landlords, and that it shall become a common Treasury to all, as it was first made and given to the sons of men.' (p.80).

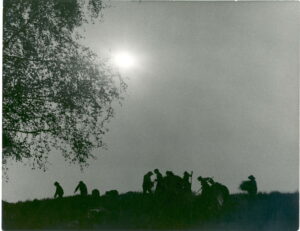

Close up of Diggers cultivating land in the 1975 film 'Winstanley', directed and produced by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo.

Close up of Diggers cultivating land in the 1975 film 'Winstanley', directed and produced by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo.

It is important to remember, at this point, what we covered in our first post about Winstanley’s millenarian beliefs. Whilst the Diggers did believe that the Spirit was making his way to rise again in men and women’s hearts – hence performing the return of Christ to Earth – differently from other millenarians, they believed that they also had to do their part in bringing about this new world. This is a very important point, because not only does it differentiate the Diggers from other groups that shared apocalyptical beliefs, but it also helps us to understand the strategy that the Diggers were conceiving: a combination of writing and acting, through which they would help the Spirit of Reason to bring about change. It is within this concept of acting that we find the idea of occupying land.

The Diggers’ agrarian occupations should be very carefully understood, because there are often various misconceptions about them: the most common one is that they defended the occupation of other people’s active property, whereas in fact they were very strict about the kind of places where it would be legitimate for them to promote occupations:

‘[…] the diggers declaring, they will neither meddle with Corn, Cattell, nor inclosure Land, but only in the Commons; […]’ (Winstanley, 1649, p. 60).

Shot of Diggers in the distance, from the 1975 film ‘Winstanley’, directed and produced by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo.

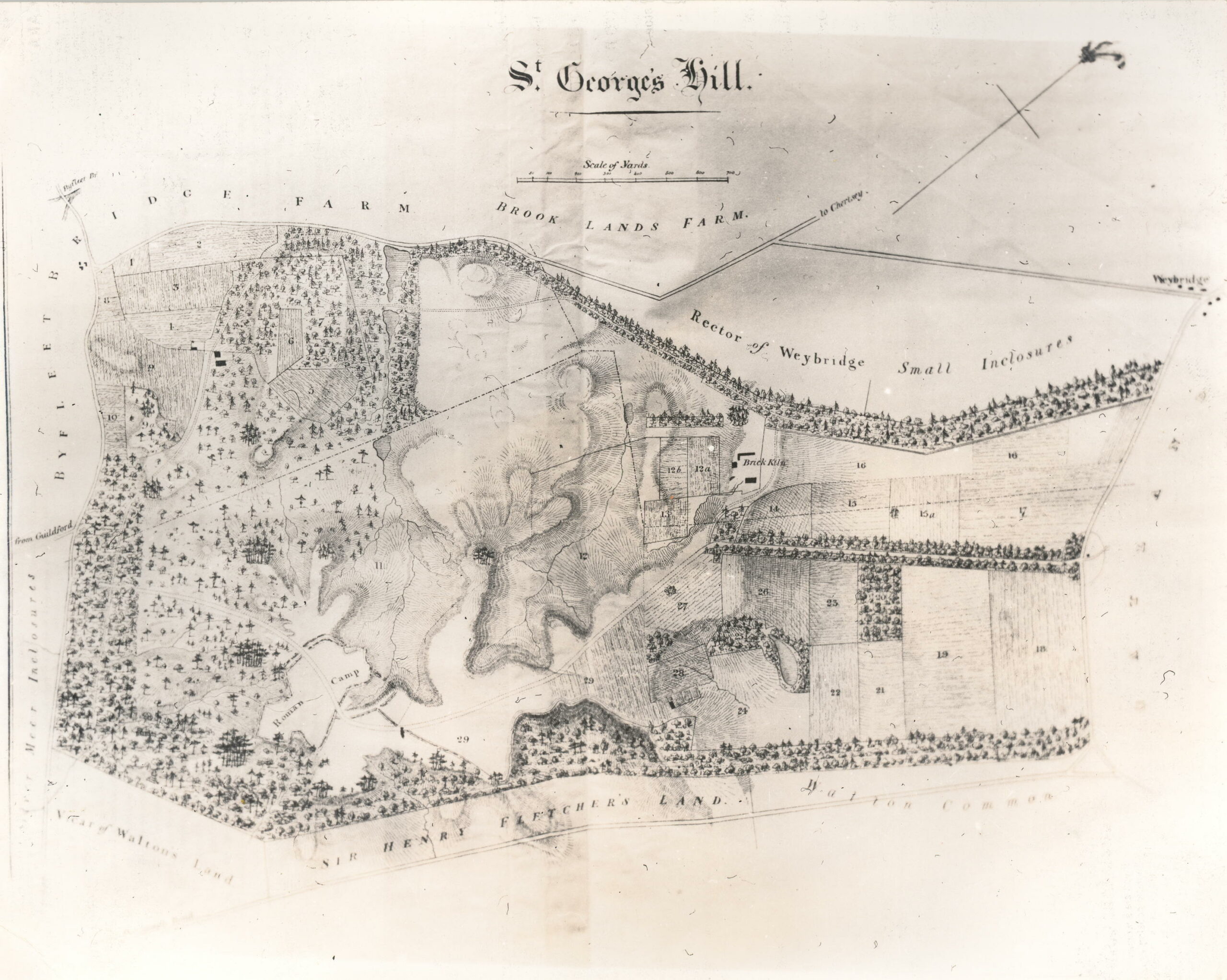

This was partly due to their attempts to dissociate themselves from other more banal forms of rural protests, such as enclosure riots (Holstun, 1991, p. 184). The areas the Diggers occupied were specifically common and waste lands, as was the case of St. George’s Hill, which was part of Walton’s commons. Moreover, Gurney (2007, p. 139) points out that St. George’s Hill had also been Crown land, therefore, in the Diggers’ view, since the king was now dead and monarchy abolished, it was only righteous that this land be restored to the common people, an argument presented by the group to Lord Fairfax (‘The Speeches’, 1649, p. 40). In addition to this, their strategy also included the denial to work for wages (Winstanley, 1649d, p. 11).

To put it simply, the Diggers only occupied places that were not being privately used by anyone else – places, consequently, that were often not even particularly good for agriculture. This was the case with St. George’s Hill itself, which was known to be an unproductive piece of land (Gurney, 2007, p. 137). The motives behind their choice of St. George’s Hill as the place for their settlement are numerous, encompassing the previously mentioned status of it, but also because it was in an area of Walton’s commons which was further from other tenants, and therefore a place less likely to cause major disruption to the locals (Gurney, 2007, p. 138).

The barrenness of the land was probably not perceived as an issue for the Diggers because they strongly believed that God would provide for them. The group also believed that once they settled their communities, the prosperity and harmony of the way of life they were proposing would ‘inevitably’ draw the attention of society in a positive way, in turn revealing how important the avoidance of any disruption to the local tenants was to them. They thought their action would lead people to give up their property and embrace the idea of common ownership and use of land (Everard et al., 1649). In other words, the Diggers believed in a sort of ‘revolution by example’ tactic.

Bearing all of this in mind, it is quite clear how different the strategies and goals of the Diggers were, compared with modern day squatters and other anarchist movements in general. Comparisons between these groups and the Diggers are often drawn in present day popular interpretations, with the Diggers’ occupations and urge to ‘act’ being sometimes addressed in terms of direct action. But for the sake of avoiding anachronisms and misleading interpretations of the past, such approximations must always be done with extreme care, as tempting as it might be to draw a parallel between such movements. As we have outlined, the Diggers had a very clear, specific understanding of how such occupations should take place: avoiding local disturbances, only on common and waste land (Winstanley, 1649e).

A map of St. George's Hill, Weybridge, before development, c.1830s-40s.

A map of St. George's Hill, Weybridge, before development, c.1830s-40s.

All of this led Winstanley, Everard and their companions to St. George’s Hill, here in Elmbridge, Surrey, in April 1649. According to Winstanley, the occupation started on the 1st of April 1649, but according to a letter by Henry Sanders, a yeoman from Walton-on Thames and supporter of the Parliament (Gurney, 2007, p. 39; 121-122), the occupation seems to have started on the 8th of April 1649’.

In the beginning, it is said that there were around five people, but during the following days this number rose to something between twenty and thirty individuals. They worked the land, sowing carrots, parsnips and the like, whilst building humble houses and bringing in farm animals (Gurney, 2007, p. 121).

We can gain a glimpse of the first local reactions to the Diggers through the correspondence of John Bradshaw, in the name of the Council of State, to Lord Fairfax, dated 19th April 1649. In this letter, Bradshaw enclosed the aforementioned report by Henry Sanders about the activities of the group (Bradshaw, 1649, p. 194; Sanders, 1649, p. 195). In this, we find the Diggers being regarded simultaneously as ‘ridiculous‘ and as a ‘threat‘.

'By the narrative inclosed your Lordshippe will bee informed of what relation hath bin made to this Councill of a disorderly and tumultuous sort of people assembling themselves together nott farre from Oatlands, att a place called St. George’s Hill; and although the pretence of their being there by them avowed may seeme very ridiculous, yet that conflux of people may bee a beginning whence things of a greater and more dangerous consequence may grow, to the disturbance of the peace and quiet of the Commonwealth.' (p. 194).

But this was only the first of the various comments and reactions about the Diggers that were expressed both in print and in manuscript. Not only do we have access to what local inhabitants, central government and diverse other groups thought about the occupation of St George’s Hill, we also have their first pamphlet that was published – not only under Winstanley’s name, but as a collective of more than fifteen signatories – by the end of that April. ‘The True Levellers Standard Advanced’ (Everard et al., 1649b), which would later be reprinted with the title ‘A Declaration to the Powers of England’ (Everard et al., 1649a), marked the entrance of the group into the somewhat ‘public” debates about the occupation of St. George’s Hill, providing their motives for being there, and disclosing their further intentions.

In our next post, we will explore the ways in which various people and groups reacted to the occupation of St. George’s Hill, the media coverage of this episode, and how Winstanley and his fellow companions disputed interpretations and characterisations of themselves through print.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to hear your thoughts!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register