Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

As mentioned previously in Blog 5, the successive attacks suffered by the St. George’s Hill Diggers forced them to relocate to Little Heath, Cobham.

We have seen that, even though the initial reactions of Cobham locals to the Diggers were rather positive, there too they eventually faced strong opposition, which had Parson John Platt as a ferocious leader

A literary genre where the author goes to great lengths to describe in rich detail how her or his ideal society would work. There are different ways of writing literary utopias: for instance, some take place in imaginary lands, such as Thomas More’s Island of Utopia. Meanwhile others, like Winstanley’s, are set in real places (the scenario for Winstanley’s utopia is England). But the main characteristic of a utopia is that it is describing and ideal society from the perspective of the author.

A woman that makes prophecies, or predictions. Often in the 17th century, such prophecies were alleged to be a gift from God himself, hence differentiating these people from witches and the like. The period of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms experienced a spike in people claiming they were prophets or prophetesses. This can be interpreted as a collateral effect of the generalised uncertainty, fear, and anxiety that characterised England, Scotland, and Ireland during the development of the wars.

Also known as ‘The Religious Society of Friends’, the Quakers started off as a group of Christian dissenters in 17th century Lancashire. They opposed institutionalised religion, the clergy, and the payment of tithes. They believed God spoke to every ordinary person, and that he should be worshiped inwardly, within people’s hearts. They also believed that women shared a relative spiritual equality to men (although this does not mean that they regarded women as equals of men in everyday life).

During the 17th century, the Quakers were persecuted in England, something that would only change during King James II’s reign, when laws granting greater religious tolerance were passed.

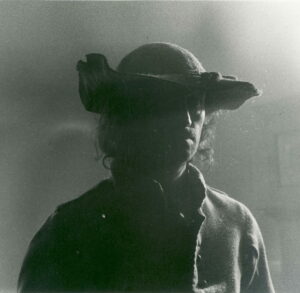

Close up of the Diggers in the 1975 film 'Winstanley'.

Close up of the Diggers in the 1975 film 'Winstanley'.

The initial settlement of the Diggers in Little Heath, which started sometime around August 1649, seemed quite promising in the beginning. They managed to build houses, as well as harvest crops across around 11 acres of land (Gurney, 2007, p. 194).

More importantly, the Diggers’ presence did not seem to trigger immediate opposition in Cobham, as had happened in Walton. The reason behind this was partly because many of the Diggers shared some sort of bond with the local community in Walton, either being originally from there, or being related to locals – as was the case of Winstanley himself (Gurney, 2007, p. 166-167). In early modern England, parish relations were a crucial part of the social structure. To be considered an outsider was something with largely negative connotations, raising suspicion and mistrust – a condition which, as revealed by the 1950s study by sociologists Norbert Elias and John L. Scotson, prevailed in smaller English communities well into the 20th century (Elias; Scotson, 2000).

Nonetheless, the type of action and reform advocated by the Diggers still troubled the local community. Eventually, people in Cobham also started to fear the Diggers’ proposed use of the commons, and attacks on their settlement, much like the ones that had happened in St. George’s Hill, were organised. Previously mentioned Parson John Platt was one of the orchestrators of such attacks. Winstanley claimed he was one of the Diggers’ main enemies in Walton, and blamed him for spreading false rumors that the Diggers were ‘a riotous people’. Below, you can read exactly what Gerrard Winstanley claimed Parson Platt had been saying about them.

‘[Parson Platt claims the Diggers are] a riotous people, and that we will not be ruled by the Justices, & that we hold a man’s house by violence from him, and that we have 4 guns in it, to secure ourselves, and that we are drunkards, and Cavaliers waiting an opportunity, to help bring in the Prince, and such like’. (Winstanley, 1649, p. 201).

Miles Halliwell playing Gerrard Winstanley in the 1975 film ‘Winstanley’.

In October 1649, the Council of State was again notified of ‘some persons that are riotously and tumultuously gathered together about Cobham’ (SP 25/94, p. 477-478), which is indicative of the fear and uncertainty the local community was starting to foster towards the Diggers in Little Heath.

The Diggers managed to somehow resist local backlash until the spring of 1650, when finally, they were driven out of Cobham. This move seems to have been a dramatic one, as it was reported that several of the impoverished Diggers had to leave their children behind, supposedly for being unable to support them (Norman et al., 1650).

It is known that after Little Heath, some Diggers, including Gerrard Winstanley, were employed by Lady Eleanor Douglas to work on her fields. Douglas was an infamous prophetess of the time. However, this work relationship did not seem to end on good terms… On the 4th December 1650, Winstanley wrote a letter to Douglas in which he complained about several wages that she allegedly owned the Diggers for their work, but refused to pay (Hardacre, 1958).

But the dismantlement of the Diggers settlement in Cobham did not mean, however, the immediate and absolute end of their ideals, nor of their actions. Between March and April 1650, two envoys from the Surrey Diggers’ occupation were arrested in Wellingborough, for ‘going about to incite people to digging, and under that pretence gathered mony of the Wel-affected for their assistance’ (Heard et al., 1650, p. 430). Thomas Heydon and Adam Knight had apparently been sent to roam the countryside seeking support for the Diggers’ cause (Gurney, 2007, p. 184), through, for instance, the collecting of funds. Before being arrested, Heydon and Knight managed to travel through Buckinghamshire, Middlesex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Huntingdonshire, and Northamptonshire (Gurney, 2007, p. 184; Heard et al., 1650, p. 432).

Despite their arrest, Heydon and Knight’s enterprise might have been somewhat fruitful. We have evidence of a few groups of ‘Diggers’ that appeared in locations where they had travelled through.

‘[…] on 26 March, digging was taking place in Wellingborough in Northamptonshire and was said to have started at “Cox Hall in Kent”. Another Digger community was soon established at Iver in Buckinghamshire, and by 1 May those involved in this new venture were claiming that digging activities had been extended to Barnet, Enfield and Dunstable, and to “Bosworth old in Northamptonshire” and unspecified places in Buckinghamshire, Gloucestershire and Nottinghamshire. With the exception of the Iver and Wellingborough communities (both of which issued manifestos) very little is known about digging activities outside Surrey’. (Gurney, 2007, p. 185).

The manifestos mentioned by John Gurney in the quotation above are the broadside ‘A Declaration of the Grounds and Reasons why we the Poor Inhabitants of the Town of Wellingborough, in the County of Northampton, have begun and give consent to dig up, manure and sow Corn upon the Common, and waste ground, called Bareshanke, belonging to the Inhabitants of Wellingborough, by those that have subscribed, and hundred more that give Consent’ (Smith et al., 1650), published on the 12th March 1650; and the broadside ‘A Declaration of the grounds and Reasons, why the poor Inhabitants of the Parrish of Iver in Buckinghamshire, have begun to digge and manure the common and wast Land belonging to the aforesaid Inhabitants, and there are many more that gives consent’ (Norman et al., 1650), published on the 1st May 1650.

The ideas contained in both these broadsides resonate well with those fostered by the Surrey Diggers, such as access to common land, and tales of hunger, poverty, and struggle. Therefore, we can interpret such broadsides as indicatives that the Surrey Diggers’ story and message was spread, heard, and even supported to an extent. Despite the resistance they faced from locals, they also seem to have echoed the grievances of some people and their communities, who tried, in their own way, to follow the Surrey Diggers’ example.

![THE BRITISH LIBRARY, London. Winstanley, G., The Law of Freedom in a Platform, 1652. Thomason Tracts, E.655[8]. THE BRITISH LIBRARY, London. Winstanley, G., The Law of Freedom in a Platform, 1652. Thomason Tracts, E.655[8].](https://elmbridgemuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Law-of-Freedom-e1666626997973.jpg) THE BRITISH LIBRARY, London. Winstanley, G., The Law of Freedom in a Platform, 1652. Thomason Tracts, E.655[8].

THE BRITISH LIBRARY, London. Winstanley, G., The Law of Freedom in a Platform, 1652. Thomason Tracts, E.655[8].

After the Surrey Diggers had long parted their ways, Winstanley still made a final attempt to have his voice heard.

In 1652, he published his last pamphlet, ‘The Law of Freedom in a Platform’. This last tract followed a different style and formula. It was written in the form of a utopia, which included a vast amount of detail in explaining and depicting how English society would work in Winstanley’s envisioned model. He listed all the laws that would exist, how society would be organized, how trade and economy would work, and so on.

Therefore, differently from previous Digger tracts, where the focus was on advocating for change and exposing criticism, in this last pamphlet he actually described his ideal English Commonwealth in great quantity of detail. And most strikingly, he dedicated The Law of Freedom to Oliver Cromwell, recognising that the Lord Protector of the Realm had power to make real change, while Winstanley himself had none (Winstanley, 1652, p. 288).

A sketch of Church Cobham, by J. Hassell, c.1800s, around 200 years after the Digger Movement. This was the community with which the Diggers had many personal links.

A sketch of Church Cobham, by J. Hassell, c.1800s, around 200 years after the Digger Movement. This was the community with which the Diggers had many personal links.

After ‘The Law of Freedom’ and the end of the Surrey Diggers, sources about what became of Winstanley and his companions become sparse. Winstanley seems to have moved on to live a rather ordinary life in Cobham, ‘characterised by a resumption of local standing and respectability with some degree of religious nonconformity’ (Davis; Alsop, 2014, p. 12). After his wife, Susan, passed away in 1664, he remarried, and with his second wife, Elizabeth, he had three children – two sons and a daughter. He seems to have become a rather respected member of the Cobham community. He served as an overseer of the poor, as a churchwarden, a corn chandler, as well as a ‘chief constable for the Elmbridge hundred in Surrey for 1671-2’ (Davis; Alsop, 2014, p. 12). At some point, he became a Quaker, and his death, on 10th September 1676, was recorded ‘in the burial register of the Westminster monthly meeting of the Society of Friends’ (Davis; Alsop, 2014, p. 12).

We might be tempted to look at the Diggers’ story through the lenses of defeat. After all, England did not abolish property, people are not living in the ‘godly brotherly community’ envisioned by Winstanley, and monarchy was restored in 1660. But the fact that we are still talking about them in the 21st century can, and should, be seen as a victory. Their words found a way into immortality, and nowadays the Digger pamphlets are of great historical relevance, since they help us to comprehend how the War affected the lives and worldviews of common men and women.

In our next and final post, we will explore the Diggers’ legacy in the present, looking into how their story and ideals have been appropriated and understood by historians and activists from the 19th century onwards.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to hear your thoughts!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register