Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

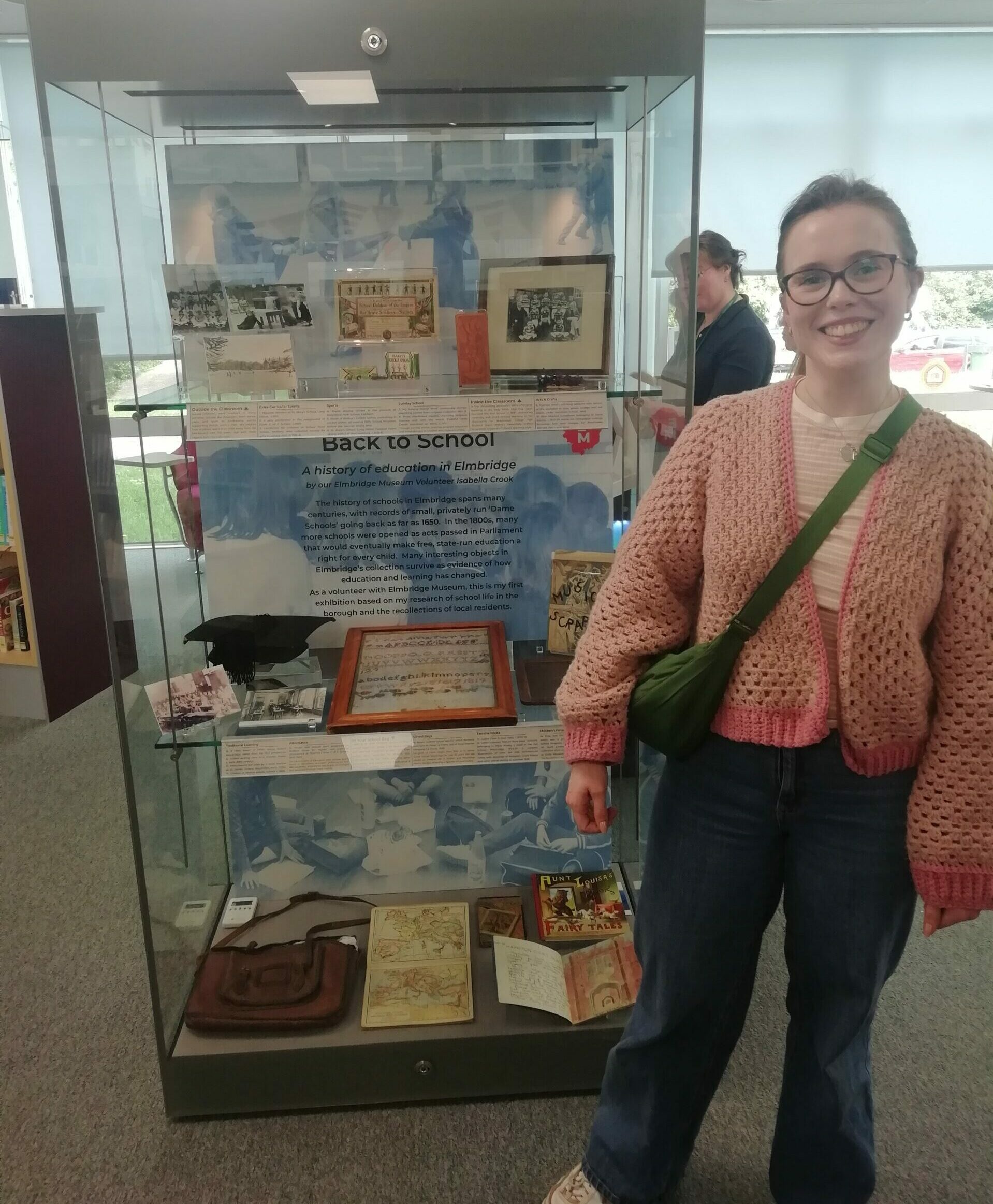

Isabella standing next to her display in Thames Ditton Library.

Isabella standing next to her display in Thames Ditton Library.

And I’ve put together this exhibition about the history of schools in Elmbridge. As a volunteer with the museum, I have been searching the collections database for interesting objects and stories that connect to historic schools in Elmbridge and how they came to be. The evolution of schools in our area reflects what was happening on a national scale and this exhibition covers some of the big developments from the eighteenth century onwards.

This online exhibition also corresponds to a physical display on at Thames Ditton library. We encourage you to visit to see more items from our collection and get a fuller picture of schools in the area. I hope you enjoy it, and thanks for reading!

Find out how to visit the display Image of Baker Street, Weybridge, c. early 20th century. This street was home to one of the oldest charity schools on record from 1732.

Image of Baker Street, Weybridge, c. early 20th century. This street was home to one of the oldest charity schools on record from 1732.

Although compulsory attendance is taken for granted now, it wasn’t until 1881 that children were required to go to school. Schools in Elmbridge began to pop up everywhere after The Balfour Education Act of 1902. This handed over control to County Councils, allowing them to set up their own schools and enabled the founding of many private schools in the area.

The school leaving age was raised from 12 to 14 years old in 1918. In the same act, fees for state elementary schools were abolished and the basis for the modern school system came to be.

The history of schools in Elmbridge, however, can be traced much further back to charity schools that were supported by church parishes and generous local benefactors. One of the oldest schools on record was founded in 1732 by Elizabeth Hopton, described by the parish registers as a ‘Charity School for the education of poor children’ in Baker Street, Weybridge.

Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold, taken from an 1818 painting by William Fry. The original is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Princess Charlotte and Prince Leopold, taken from an 1818 painting by William Fry. The original is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Early schools were also referred to as ‘dame schools’, named after the women who set up these schools and taught small groups of local children for a fee of a few shillings.

It was probably a dame school that Princess Charlotte was noted for visiting regularly in Esher after moving to Claremont upon her marriage in 1816. She was known to visit during her walks and hand out merits for good work.

The royal family’s connection to Esher schools continued with Queen Victoria’s youngest son, the Duke of Albany, being instrumental in founding Esher Church of England School.

His widow, Helena Frederica Augusta, had a continued presence in the school life, inspecting the pupils in their writing, sewing and scripture. The Duchess paid special attention to needlework and awarded the student with the best sewing a prize every summer.

Image of Esher school, Esher Village Green

The Esher National and Infants’ School was opened in 1859, with 362 pupils. Prior to its opening, a school had been held in Esher on the site of the old workhouse since 1837.

The majority of Esher’s population did not have much use for education at the time. The children of poor families were needed for work at home or were employed working in the fields.

Image of Esher School pupils and master

When the proposal to build a new school was made, a large portion of the funding came from royalty with King Leopold of Belgium (uncle to Queen Victoria) donating £400 to the effort.

The school stayed open for many years until 1968.

Image of Vivienne Jennings, aged 10

Image of Valerie Jennings, aged 10

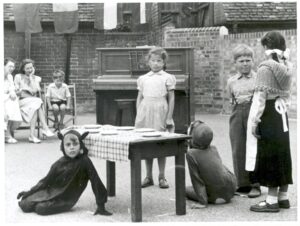

Here are the Jennings sisters who were pupils of the school in 1953, posing against a backdrop celebrating Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

And here, Valerie Jennings is taking part in the school play – second from the left in the top image.

Images of a school play performed in the playground of Esher C of E School, c.1950

Copied sketch of Thames Ditton School from Church Walk

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, the National School movement played an integral role in the founding of schools in Elmbridge. Led by Andrew Bell, the movement was closely connected to the Church of England and pressured parliament to give its first grants to education.

Black and white photograph of a class from Thames Ditton School, Church Walk, Thames Ditton, c.1900

Enacted in 1833, new legislation restricted employing children in factories and granted £20,000 towards schooling. It was this funding that enabled the founding of Thames Ditton National School in 1844.

When it first opened, Church Walk School was catering to a small population of 1288 people. These would have been farm labourers and people in trades connected to the river. Children were needed to help their parents with the harvest, so every year the school closed in August.

The area was remote and poorly connected until the arrival of the railway in 1849, the school expanding to hold two classrooms in 1877 to cope with the rising population. The photograph on the right shows a class of pupils from the turn of the century with their teacher Miss Churchfield.

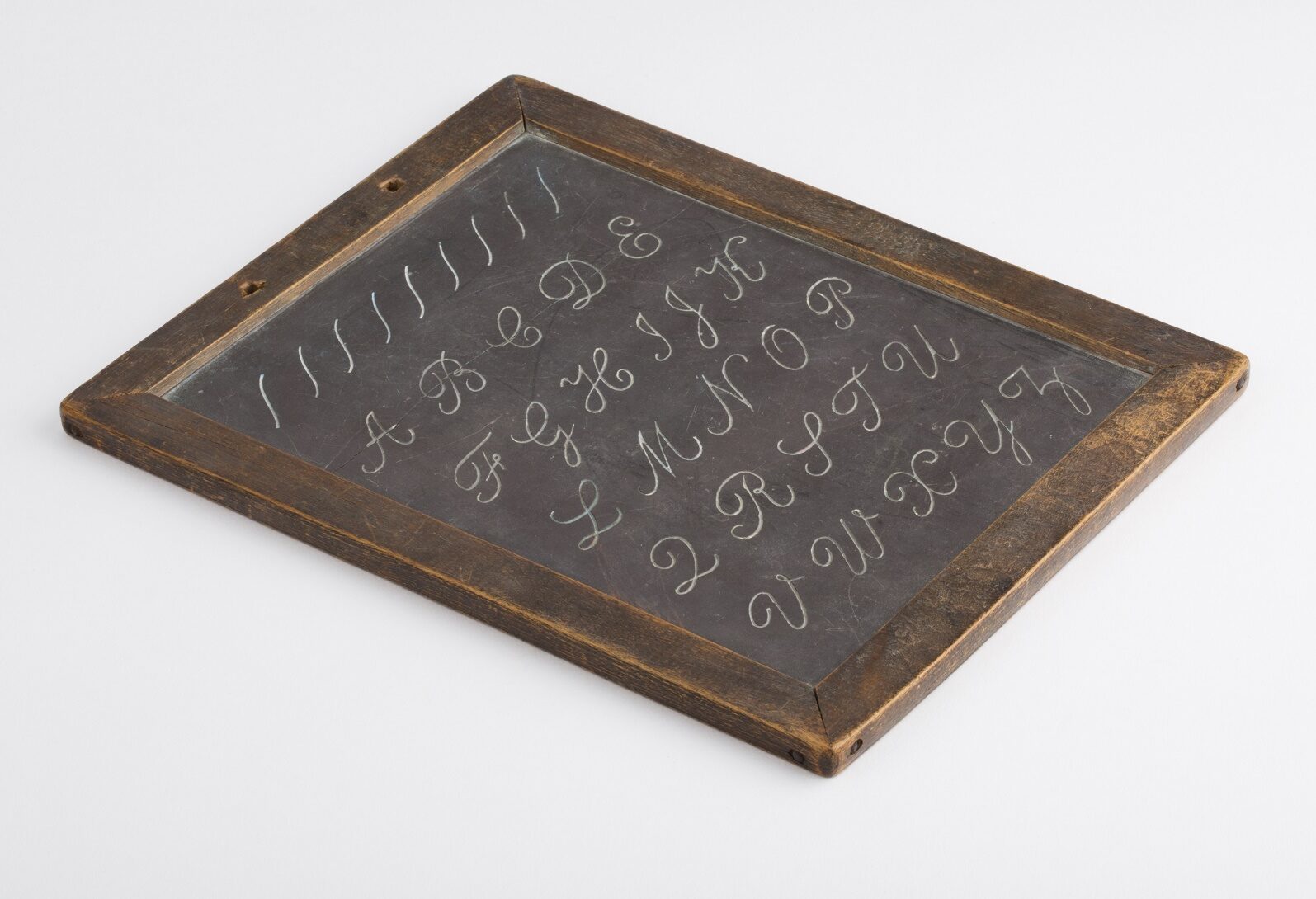

This Victorian school slate is from Sunbury. There are alphabet capitals, in copper plate style writing, on one side, and clear slate on the other, in a wooden frame. Chalk and slates were widely used in early schools to teach children to write, before whiteboards and electronic tablets came into existence.

Image of Claygate Girls School, 1898

In the schools of the nineteenth century that separated boys and girls from aged 7 upwards, sewing and needlework was especially encouraged as a subject of study for young women.

What was considered a ‘feminine accomplishment’ among the upper and middle classes, was an important, practical skill for girls from poorer families. Sewing was very useful in many of the manufacturing processes that were emerging as part of the Industrial Revolution during the late eighteenth century. In rural areas like Elmbridge, learning to sew would prepare girls for domestic life or life in service.

Image of the Royal Kent School, Oxshott, 1896

Below are a range of sewing samplers made by young women in Elmbridge throughout the nineteenth century. A piece of fabric with different stitches and patterns, they were used to practice and demonstrate skills in needlework. They also serve, however, as a fascinating record of the lives of young women.

The earlier samples made with elaborate embroidery and expensive silk thread were probably made by girls from wealthier backgrounds.

The inclusion of the alphabet and numbers in rows, display a record of the education system’s emphasis on the ‘3 R’s’: reading, writing, and arithmetic. This was important to include as samplers were frequently presented to school Trustees as evidence of the pupils grasp of numbers and letters.

Ellen displays her mastery of the alphabet in the top four lines and writes 'To speak the truth is always right' below.

Miss Plumbridge has sewn her alphabet in bright green, blue and red wools. Stitching on a blue background, the sewing in white wool on the top line reads 'Hersham School'. White wool is used again below the flowers on the bottom half to spell out the author's name and the date.

This sampler draws heavily from biblical teachings, showing Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden embroidered in petit point. A verse is sewn above the tree of life reading:

'My dear Redeemer is above

Him will I go to see

And all my friends in Christ below

Shall soon come after me.'

This is another more elaborate sampler with a formal border pattern of trees, flowers, and animals. '1827, Eliz. Morey aged 11 years' is inscribed above the small house at the bottom of the sampler.

Looking at what children carried in their school bags can reveal a lot about what was deemed important to learn and how pupils were expected to absorb this information. By the 1900s, subjects were expanding well beyond the traditional 3 R’s, reading, writing and arithmetic.

School was not all about time spent in the classroom and many people most clearly recall time spent on the playground.

This Victorian school that sat on the edge of Hersham Green had plenty of space for children to explore.

Attending Hersham School before the First World War, a pupil called Nellie remembered playing a game called ‘Fool, Fool’.

Fool, fool, come to school

Pick me off a blackbird

Pick me off a thrush…

The game would go on with children being picked off as the name of their bird was called and they would jump forward and fall down.

This schoolyard game, however, also recalls the harsh punishments children received for mild misbehaviour. On one occasion, Nellie was caned for playing the game – “apparently when I fell down, I showed my knickers and this was very wrong”.

Image of children at Hersham Infants School, 1908

Old photograph of Hersham Green and pond with the school in the background, c. 1900-10

Old photograph of Hersham Green and pond with the school in the background, c. 1900-10 Sports clubs also became a large part of the school experience, different schools offering all sorts of different opportunities to exercise and play.

Heathlands Tennis Lawns, Weybridge, c.1912

Football team from Walton Central Boys’ School, Walton on Thames, 1915

Weybridge Church of England School (St. James) netball team, 1947-8

Hersham Infants School football team, c.1953-4

Mount School sports day, Oatlands, c.1930s

Mount School sports day, Oatlands, c.1930s

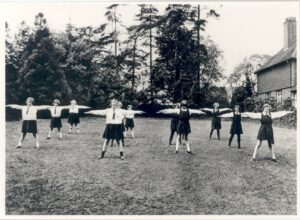

A Drill Class at Heath House School for Girls, Weybridge, c.1936

Pupils playing cricket in the grounds of Hatchford Park School, Cobham, c.1960s

There were also celebrations to mark the coming of spring.

Maypole dancers from St. Mary’s School, Long Ditton, c.1911

Weybridge Church of England School (St. James) during the May Day Festival, 1949

Weybridge Church of England School (St. James) during the opening procession of their School Folk Dance Party, c.1950s

And opportunities to act in school productions.

Class of children in a school play, St. Mary’s School, Long Ditton, c.1919

A line of boys in a production called ‘The Wooden Soldier’, at St James’ School, Weybridge, 1930

And so the grounds outside the classroom became just as central to the school experience, as the time spent indoors.

Class of girls outside school at Princess Mary Village Homes, Addlestone, 1930s

Children playing outside Old School Cottage, Baker Street, Weybridge, 1957

The artist who painted this watercolour and the date they painted it is unknown, but we do know it dates to pre-1970. It depicts children playing on Hersham Green next to the Victorian school, c. 1910-20.

When a new Sunday school was set up for Hersham and Walton in 1820, the protestant reformers who led the services considered the areas to be ‘in a sad state of spiritual destitution’. This conclusion was drawn from the locals tendency to play sport and attend prize fights on a Sunday rather than attending church services. Equally damning was the fact that services and the Sunday school had to be held in the local public houses, the ‘Fox and Goat’ in Hersham and the ‘Bear Inn’ in Walton.

A century later, Sunday schools continued to educate in biblical teachings but gave more allowances for leisure. This included not only sport but amateur dramatics and concert parties for their congregations.

Into the late 20th century, Sunday schools continued to thrive and become more informal and interactive.

Image of St James's Infant Sunday School, 1922

Image of St James's Infant Sunday School, 1922

Esher Sunday School, 1937

Esher Sunday School, 1937

Black and white photograph of Children of St. Andrews Church Sunday School, Hersham, 1945

Black and white photograph of Children of St. Andrews Church Sunday School, Hersham, 1945

Photograph of the Rev. Graham Holdaway conducting Sunday School in existing St. John's Hall, Walton. c.1970s

Photograph of the Rev. Graham Holdaway conducting Sunday School in existing St. John's Hall, Walton. c.1970s

Sunday schools had begun to be set up in the eighteenth century in response to the lack of schooling for poorer children. Their role as the primary source of education changed, however, when the state began to support and mandate education for all by the 1870s.

Where adults and children had once attended these schools to learn basic reading and biblical teaching, the Sunday school now evolved to offer more recreational activities like sports, music, and social clubs.

Image of The Claygate Sunday School outing, 1895

Image of The Claygate Sunday School outing, 1895

Black and white photograph of Sunday School Choir and Orchestra, probably taken in the late 1920s to 1930s.

Black and white photograph of Sunday School Choir and Orchestra, probably taken in the late 1920s to 1930s.

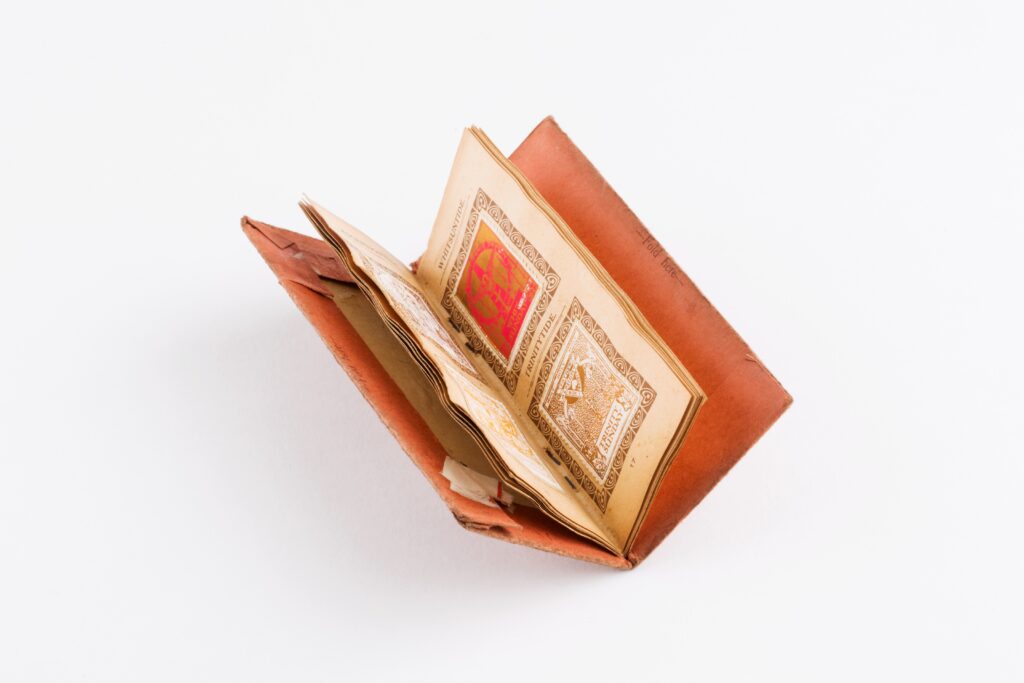

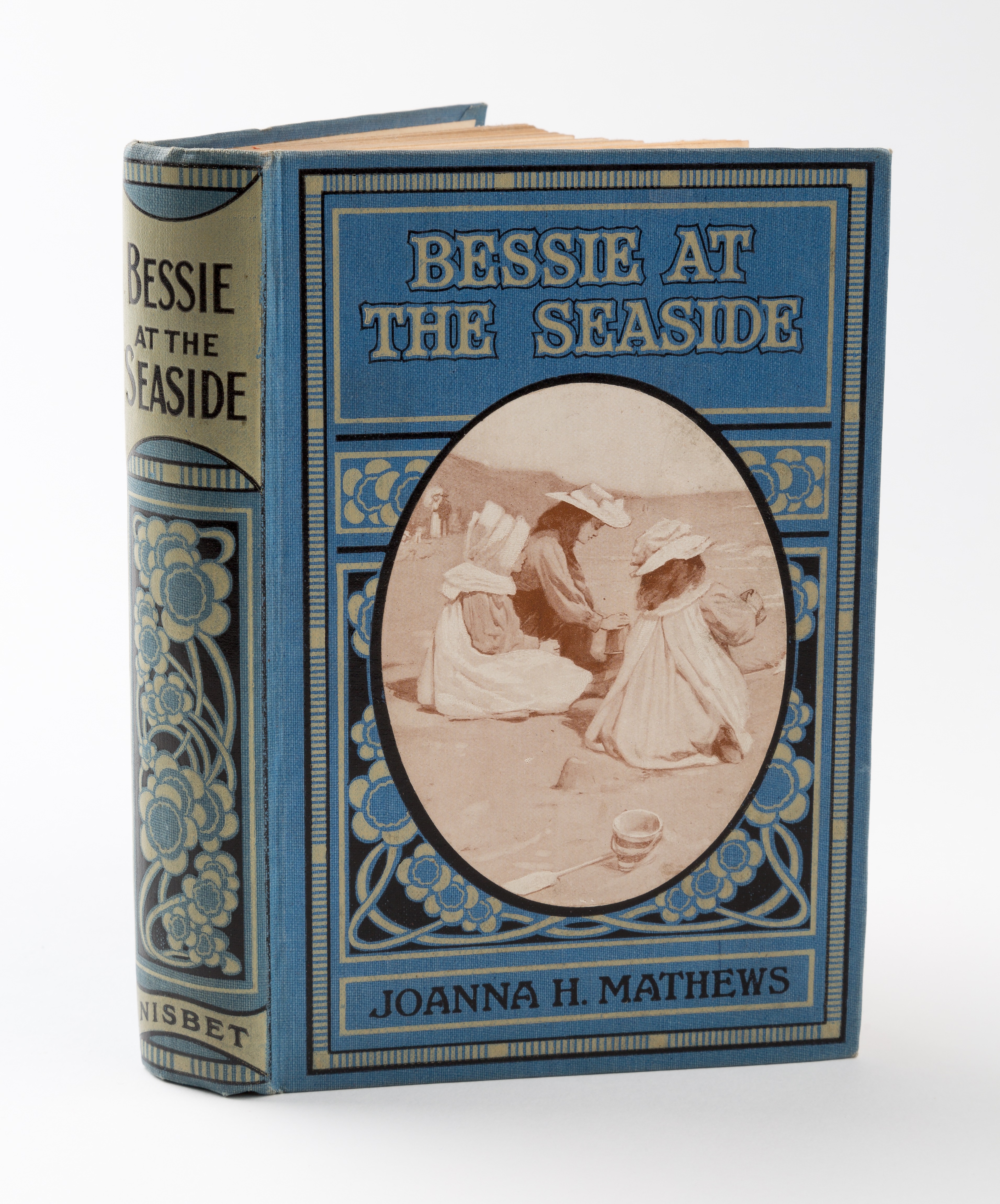

To keep attendance and award diligent pupils, Sunday schools often gave out rewards to their attendees. These could be in the form of fiction books, stamp collections that taught different parables, or something more expensive like these religious medals.

Awarded to Emily Taylor for her good performance at Sunday School, this tripartite medal shows angels and saints with the inscription ‘Faithful Unto Death’.

Three interlinked medals depicting religious themes, with the words 'Faithful Unto Death' inscribed on each. These were awarded to Emily Elizabeth Taylor at St. Mary's Sunday School in Oatlands, c.1912.

Three interlinked medals depicting religious themes, with the words 'Faithful Unto Death' inscribed on each. These were awarded to Emily Elizabeth Taylor at St. Mary's Sunday School in Oatlands, c.1912.

'My Sunday Stamp Book', owned by Emily Elizabeth Taylor of St. Mary's Sunday School in Oatlands , 1912-13.

'My Sunday Stamp Book', owned by Emily Elizabeth Taylor of St. Mary's Sunday School in Oatlands , 1912-13.

'Bessie at the Seaside' children's book by Joanna H Matthews, which was awarded as a prize for good attendance and behaviour. It is inscribed 'St Andrew's Sunday School, Cobham. Prize Lena Wye, December 1915'.

'Bessie at the Seaside' children's book by Joanna H Matthews, which was awarded as a prize for good attendance and behaviour. It is inscribed 'St Andrew's Sunday School, Cobham. Prize Lena Wye, December 1915'.

Miss Eva Gilpin with her first 4 students in 1896, at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Sadler in Weybridge. This was just 2 years before she founded The Village Hall School.

The Elementary Education Act of 1870 had established school boards and worked to make schooling compulsory for all children up to thirteen. There was further reform in 1902 with the Balfour Education Act. This got rid of school boards and put all schools under the control of county and borough councils. As a result, it became a lot easier to set up private schools and many popped up in Elmbridge in the following years.

Photograph of Miss Eva Gilpin, Headmistress of the Hall School, Weybridge. This was taken in 1938, four years after her retirement from the school.

One such school was the progressive Hall School, set up in 1898 by Miss Eva Margaret Gilpin in Weybridge.

Eva was the second daughter of Edmund and Margaret Gilpin, a Quaker family from Ackworth, West Yorkshire. She was born in March 1868 and initially educated in Ackworth, but financial crisis meant that the entire family had to leave school at an early age to earn their living. Eva moved around the country for work, with her first job post at Kensington School in London and moving in 1889 to Leeds, to act as a governess to her young cousins. This small class was soon joined by another cousin, Michael Sadler. Michael’s parents were so impressed by Eva’s teaching capabilities and unique approach that they soon arranged for her to join them at Eastwood, in Weybridge, and continue as governess to Michael and a small group of other local Weybridge children.

In 1898, the class moved to the Village Hall in Princes Road, and became known as the Village Hall School – later to be known simply as ‘The Hall School’. The school gradually expanded its numbers to around 100 students, with the youngest in a separate Kindergarten and boarders living at the Hall School House in Queen’s Road.

After over 40 years of educational achievement, Eva Gilpin retired in 1934 at the age of 66. In December of that year, she married Sir Michael Sadler. They lived in Oxford for another 6 years until Eva’s death in 1940. The photographs below, from a 1920s school prospectus, show the varied curriculum offered by Miss Gilpin during her years at The Hall School.

This architect's plan shows the schools position on the corner of New Road and York Road, as well as the internal class rooms, hall, art room, open yards, and sports courts.

There is plenty of evidence of local schools supporting the troops during both the First and Second World Wars in Elmbridge Museum's collection. The First World War certificates for fundraising shown below demonstrate how children were taught to have pride in Britain's participation in the War. Britain's intrinsic place in the world and its 'ownership' of territories far and wide as part of its huge empire were proudly emphasised. War was presented as a noble and honourable pursuit, with stylised images of soldiers receiving gifts and holding flags, far from the reality of what life was really like on the front line. Scrolling right, we can see how some local schools also supported the Second World War, over 20 years later. The photographs of the Women's Junior Air Corps at Hinchley Wood School demonstrate how schools were often mobilized as spaces to prepare pupils for military service, but also to encourage patriotism and boost morale among students.

This was presented to Emma Denby, a student at School Road School in Molesey. It congratulates Emma on sending 'some comfort to the brave Sailors & Soldiers of the British Empire who are fighting to uphold Honour, Freedom and Justice.' Above this, it presents a map of 'How the world is at war', showing the British Empire, its Allies, and its enemies.

This was presented to Alfred Adley, a 6-year-old student at a school in Thames Ditton. At the top of the certificate it reads 'A Happy Xmas 1916'. Underneath this, it says that it is 'A signed wish from the school children of the Empire who sent Christmas gifts to our Brave Soldiers and Sailors', certifying that Alfred 'has helped to send some comfort and happiness to the Brave Men who are fighting to uphold the Freedom of our Glorious Empire'.

This was presented to Emma Denby, a student at School Road School in Molesey. It certifies that Emma 'has helped to bring happiness on Christmas Day to our brave sailors and soldiers, who are fighting for honour, freedom & justice.' On the left, a small scroll states that 'the underlying motive of the Overseas Club [who issued the certificate] is to promote the unity of British subjects the world over.'

This photograph shows Hinchley Wood Secondary School's 'Women's Junior Air Corps' doing a drill in the school playground. This was a voluntary organisation set up in March 1940, to which girls aged between 14 and 17 could join up during the Second World War. The idea was that the Corps would provide pre-entry training for the services during wartime.

The Women's Junior Air Corps used to meet 2 nights a week for drills, typing, shorthand, and other training activities. Once they turned 18, girls could no longer be in the Women's Junior Air Corps (17 years old was the upper age limit), and instead they might be called up into the services or war work.

This image shows girls in the Women's Junior Air Corps doing physical training in formation.

This image shows girls in the Women's Junior Air Corps doing physical training in formation.

This photograph shows three young student officers of the Women's Junior Air Corps.

In this interview conducted in March 2020, Helen, a participant in Elmbridge Museum’s ‘Memories of War’ project, shares her memories of being in the Junior Air Corps and completing training in Walton when she was at school.

Photograph of St. James’ School and buildings taken from Baker Street, spring / summer 1983.

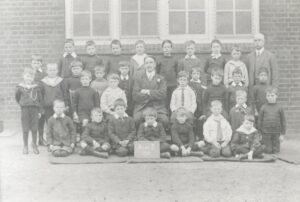

Boys’ Form I of St. James’ School, 1911. The Headmaster, Mr. Carpenter, can be seen sat in the middle. Just 3 years after this photo was taken, the First World War began, a conflict which would end Carpenter’s life along with countless other local men and women. It is particularly poignant that many of Carpenter’s students pictured here likely also went onto fight during the Second World War over two decades later.

St James’ Junior School dates back to the mid-Victorian era, and originally stood in Baker Street, in Weybridge. In 1894, a bigger school was built next door and the original school building became the caretaker’s house.

During the First World War (1914-18), the school building was used as temporary accommodation for soldiers on their way to fight in the First World War. Across Elmbridge and the whole country, vast numbers of men were called up to fight in the First World War when conscription to the armed forces was introduced by the Military Service Act in January 1916. The act enabled the government to call up all single men aged between 18 and 40 for military service. The only people who were exempt were widowers with dependent children, or religious ministers. As a result, many schools were affected by teachers being called up to fight. St. James’ School was no exception, and the school’s headmaster, Mr Carpenter, was sadly killed during his military service.

The school was also affected by the Second World War (1939-45): one night during the Blitz, a bomb hit the empty school building, destroying two classrooms, scattering books over local residents’ roofs and gardens. Luckily, no one was killed or injured by the bomb, but the school’s piano was reportedly found half way up Baker Street.

In this recorded interveiw from March 2020, Helen, a participant in Elmbridge Museum’s ‘Memories of War’ project, talks about two occasions when her school was bombed and students helped to clear up.

Childhood in Elmbridge has changed radically since Queen Victoria's reign ended in 1901. However, the themes of home life, education, and play have remained timeless. Here, we assess the changes and continuities within the lives of local children over more than 100 years.

Go to the Young Victorians online exhibition

Leave a Comment

We'd love to know what you thought of this online exhibition, or if you have memories of your own school experience to share.You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register