Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

A photograph of the front face of Apps Court, with the Gill family gathered on the steps at the front entrance.

A photograph of the front face of Apps Court, with the Gill family gathered on the steps at the front entrance.

From dozens of surviving photos, paintings, letters and personal memoirs in Elmbridge Museum’s collection, we can piece together the fascinating story of the Gill family. Gradually, a detailed picture emerges, not only of the practicalities and social norms of Victorian life, but of this family’s complex relationships, thoughts and feelings towards each other.

Their tale is one of fortune, tragedy, formidable matriarchs and familial affection which spanned the ages.

The story begins in 1855, when the young family arrived at Apps Court in Walton-on-Thames.

The rise of the Gill family coincided with the flourishing of the Victorian era. By the time of Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837, the industrial revolution was already bringing about major technological advancement through the mechanisation of factory production and labour.

Steam power was a major catalyst for change, not only in factory production, but in transport, too. It had become essential to find a way to transport goods and the burgeoning population more efficiently around the country, and in 1825 the first steam railway, the Stockton and Darlington, was opened. Not long after this, in 1830, the first modern passenger railway was opened in the form of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and after this passenger railways saw an explosion across the UK and the world.

As Chairman of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway with headquarters at Manchester Victoria Station, 34-year-old engineer Robert Gill had been present at the opening ceremony of the Liverpool and Manchester railway on 15th September 1830. He was one of the men cashing in on this new profitable development. A good friend of George Stephenson – often considered the ‘Father of Railways’ – the pair worked together on the Manchester and Leeds Railway. The family memorial recalls that Stephenson and Gill ‘thoroughly understood each other, and worked in unison on promoting and making Railways, during the anxious stages of the great work’. Gill was responsible for cutting the first sod for the line in 1837, and was frequently found working on the line ‘for days and nights in succession… only getting snatches of sleep.’ The finished result was eventually opened for business in 1842, to much popular press, and Robert was awarded £2000 in recognition of his services.

Robert continued to amass money in the years after this. By the time of his second marriage in 1846, he was reportedly earning £10,000 a year, although, as described by his daughter Frederica, he ‘was not a lover of money for its own sake & did not take advantage as he might have done of selling out’. He and a group of businessmen purchased the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in 1851, re-erecting it in Sydenham, and Gill continued to be one of its directors for several years. In 1855 – with their newly accumulated wealth – Robert, his three young daughters, and pregnant wife moved from Mansfield Woodhouse in Nottinghamshire to Apps Court, in Walton-on-Thames.

Hardworking Robert Gill excelled in his job in the railways, as can be seen from this transcribed letter. Written to Robert in 1831, it congratulates him on his swift actions which prevented an accident with potentially ‘fearful’ consequences, and assures him that his skill will soon be rewarded.

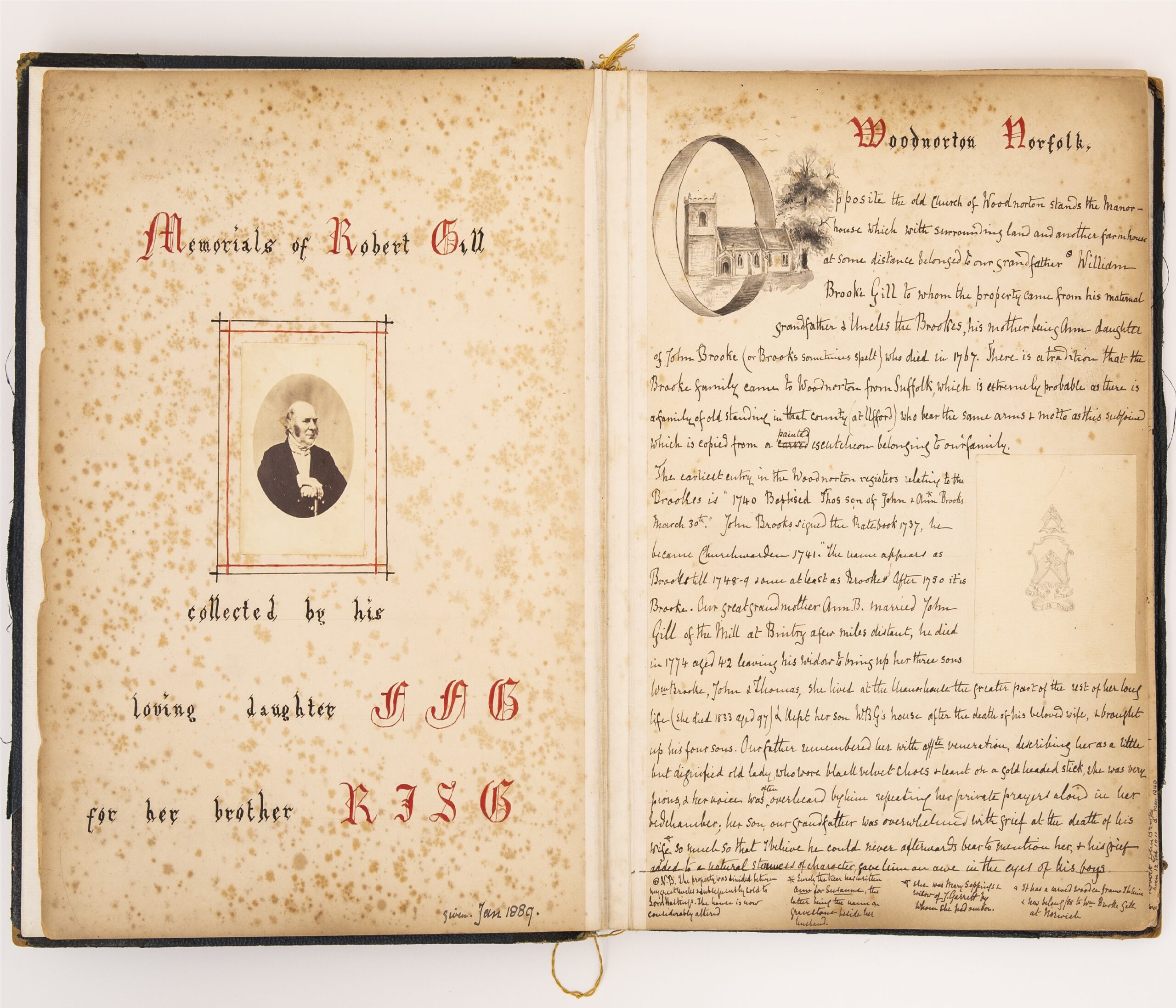

The first pages of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889, containing an image of Robert Gill on the left and a hand-written account of his early life on the right.

The first pages of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889, containing an image of Robert Gill on the left and a hand-written account of his early life on the right.

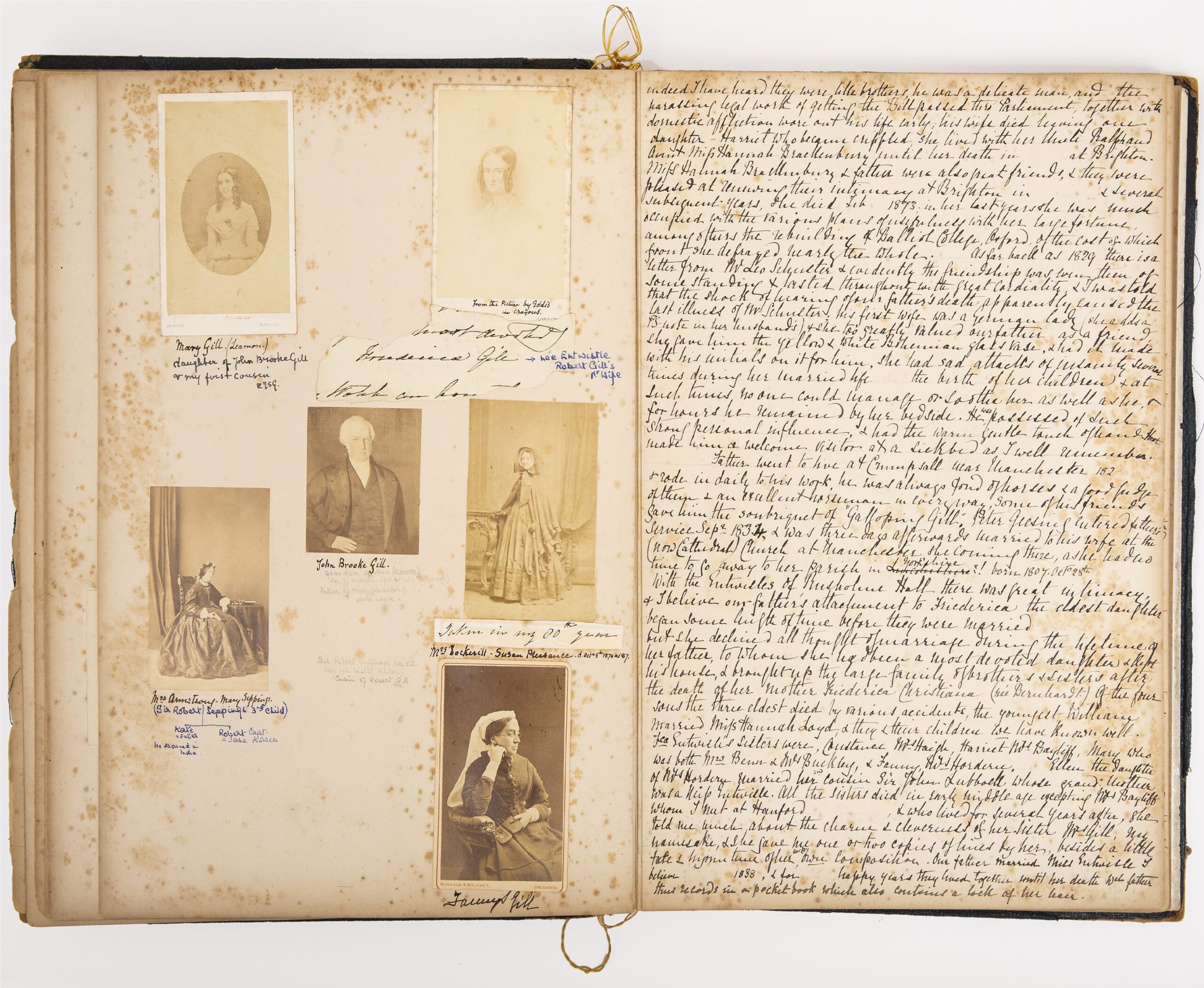

The most important item we have in the museum collection relating to the Gills is the ‘Memorials of Robert Gill’ family album. Made up of hand-written memoirs, a manuscript of Robert Gill’s life, photographs, drawings, two family trees and printed scraps that include the story of the house and its last occupants, the album is an unusually early study in family history. It was started by Robert Gill’s eldest daughter, Frederica, and given to her younger brother in January 1889. At the back of the album are a number of additional pages devoted to the life of this younger brother – named Robert John Seppings Gill – written much later on, by his wife.

The ‘Memorials’ gives fascinating insight into both family life in the Victorian era and the strong desire to cement the family’s affluence and status. Frederica Gill does this by emphasising the Gill family’s historical name and lineage and by stressing her father’s achievements.

The ‘Memorials’ have been used and referenced throughout this online exhibition, and some passages provide a tantalising glance into the family’s life together.

Some pages of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889, containing images of various family members on the left and a hand-written account of Robert's life on the right.

Some pages of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889, containing images of various family members on the left and a hand-written account of Robert's life on the right.

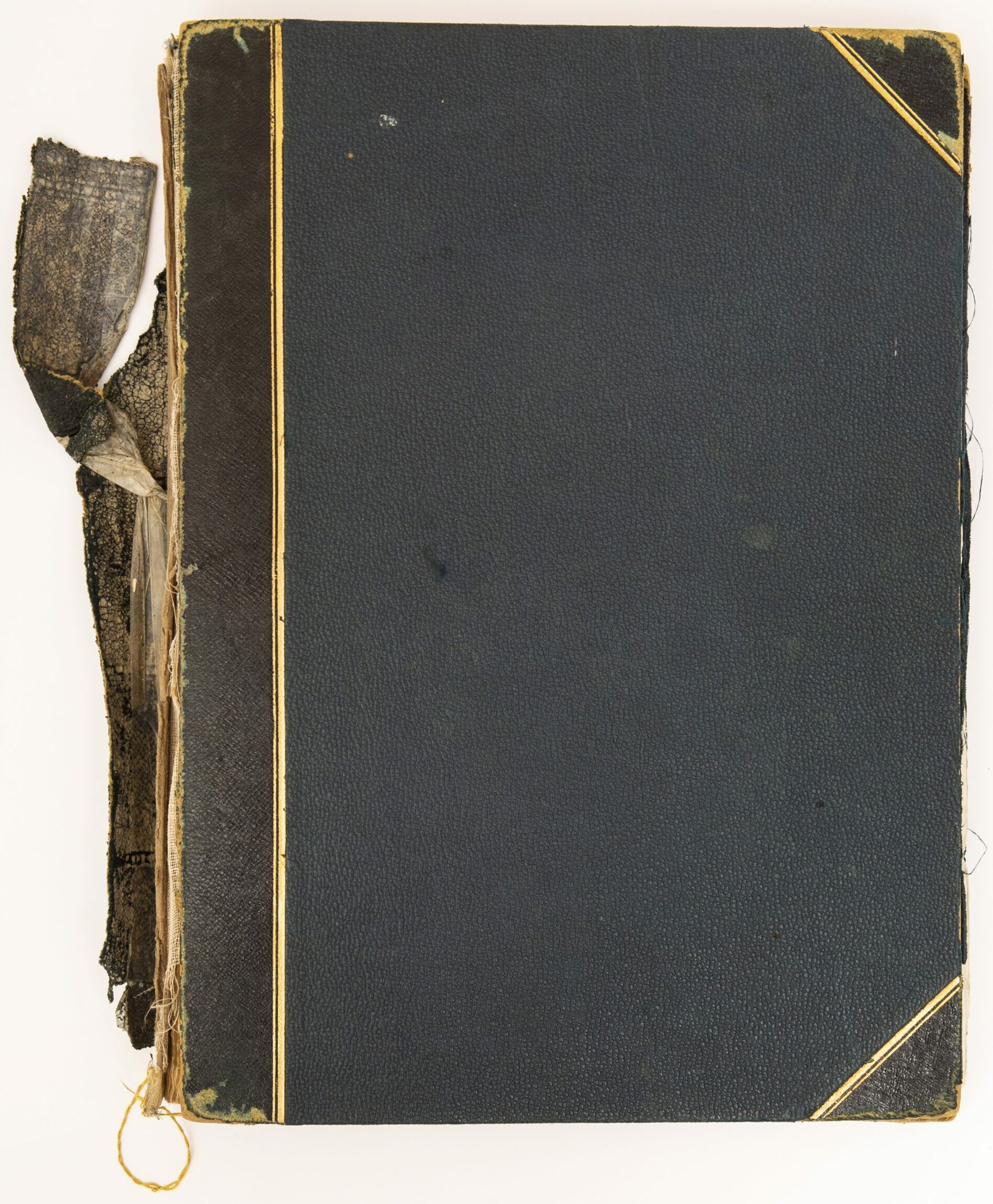

The front cover of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889. The album has a hard cover, bound in blue fabric and leather with some gold tooling.

The front cover of the 'Memorials of Robert Gill', 1889. The album has a hard cover, bound in blue fabric and leather with some gold tooling. Fanny Need was the second daughter of John and Mary Need of Sherwood Hall, Mansfield Woodhouse (Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire). She was the granddaughter of William Welfitt, a notable Prebendary of Canterbury Cathedral for over forty years, and therefore came from reasonable status.

On Tuesday 29th December 1846, Fanny married widower Robert Gill in a ceremony in her hometown of Mansfield Woodhouse. The couple had met after Robert had moved to Mansfield Woodhouse shortly after the death of his first wife. They went to London and then Brighton for their honeymoon, staying at the Bedford hotel and indulging in their mutual love of horses by riding on the downs.

Over the course of their marriage, which ended with Robert Gill’s death in 1871, Fanny had five children. Evidence suggests that Fanny was both a well-educated and well-respected member of the local community and her own family, with Elmbridge Museum holding a number of surviving letters sent to and from her during the course of her life.

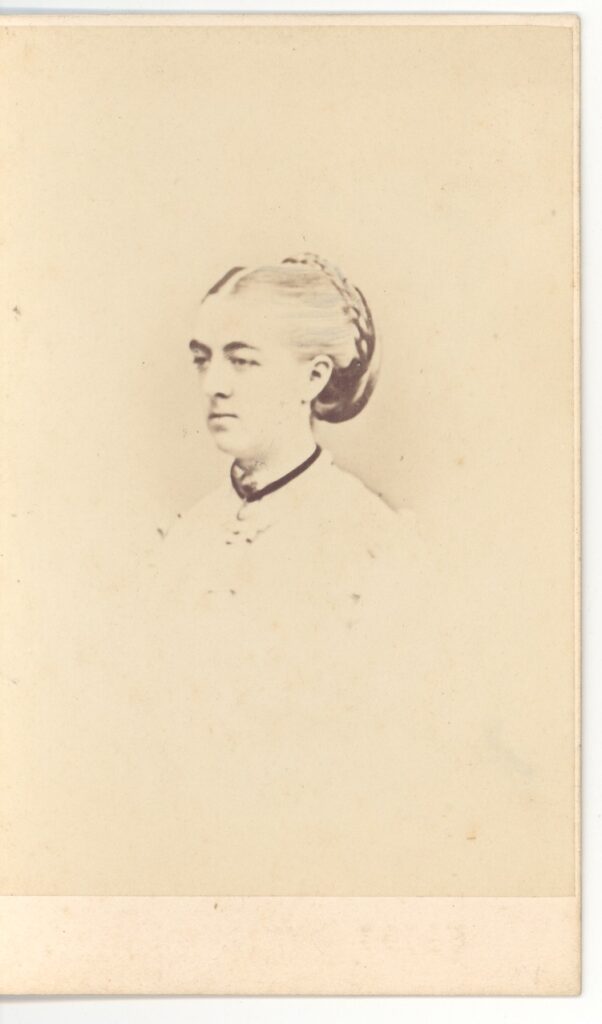

Carte de Visite of Fanny Susannah Gill, undated

Carte de Visite of Fanny Susannah Gill, undated

Carte de Visite of Fanny Gill, wearing a lace cap over a crinoline dress - undated.

Carte de Visite of Fanny Gill, wearing a lace cap over a crinoline dress - undated.

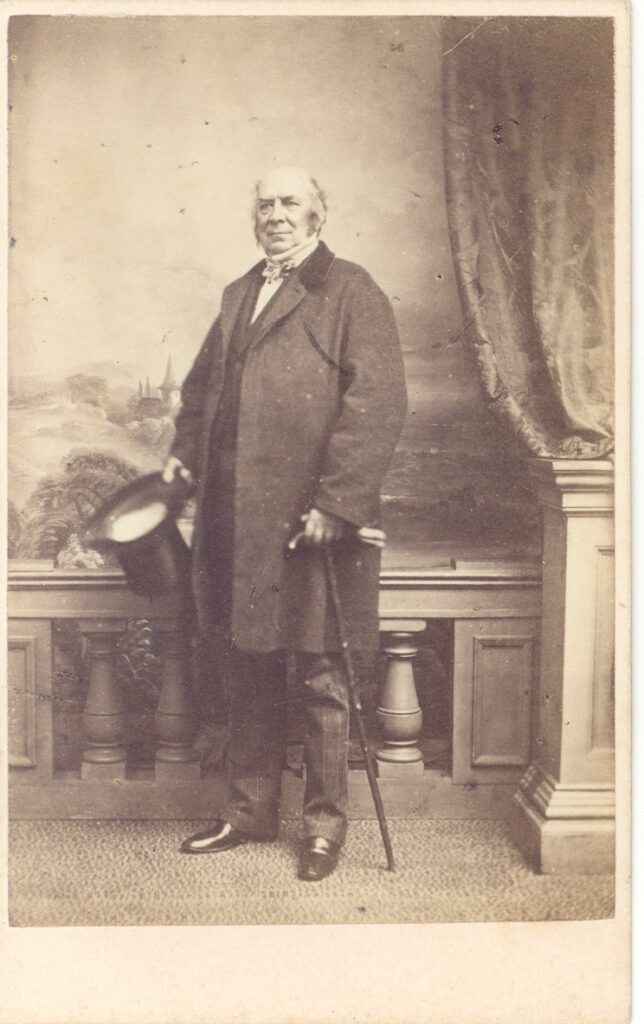

Robert Gill was the third of four sons born to William Brooke Gill and Mary Seppings. After the death of his young mother when she was 35 and he was just 3 years old, Robert was brought up in the Gill family manor house in Woodnorton, Norfolk, by his grandmother Ann Gill (née Brooke).

In 1838, Robert wed Friederica Entwistle. The pair were married for 5 years, in which time Robert opened the aforementioned Manchester and Leeds Railway, before Friederica sadly died in 1843. She left Robert a widower at just 47 years old, but by 1846 he had remarried Fanny Need and moved to live with her in Mansfield Woodhouse. The pair had three daughters here before moving to Apps Court in Walton, after which they had another daughter and son.

In ‘The Memorials of Robert Gill’, written by his daughter Frederica, Robert is described as having ‘a quick and passionate temper & could be flashingly indignant at any wrong doing and meanness, but though very impatient of stupidity was tenderly pitiful of want and sickness.’ She also describes her father as having a ‘strong will and cheerful spirit, with a keen sense of the humourous side of all things’ which was of great benefit to him during his exhaustive work on new railway projects in his earlier life.

After Robert’s death, his widow Fanny gifted a ‘handsome new pulpit of Caen stone and Devonshire marble, built in the gothic style’ to the Parish Church of Walton. The sermon at the dedication service was preached by his son, also named Robert, who had been just 12 when his father died. The dedication reveals this family’s devotion to their husband and father, as well as their devout Christianity.

Carte de Visite of Robert Gill c. 1860s.

Carte de Visite of Robert Gill c. 1860s.

Oil painting of Robert Gill by Victorian portrait artist William Bradley, painted when Gill was aged approximately 35.

Oil painting of Robert Gill by Victorian portrait artist William Bradley, painted when Gill was aged approximately 35.

Carte de Visite of Friederica Entwistle, the first wife of Robert Gill.

Carte de Visite of Friederica Entwistle, the first wife of Robert Gill.

The first child of Robert and Fanny Gill, Frederica was born in 1847, the year after the couple’s marriage. She spent the first 8 years of her life in Mansfield Woodhouse before the family moved to Apps Court in 1855.

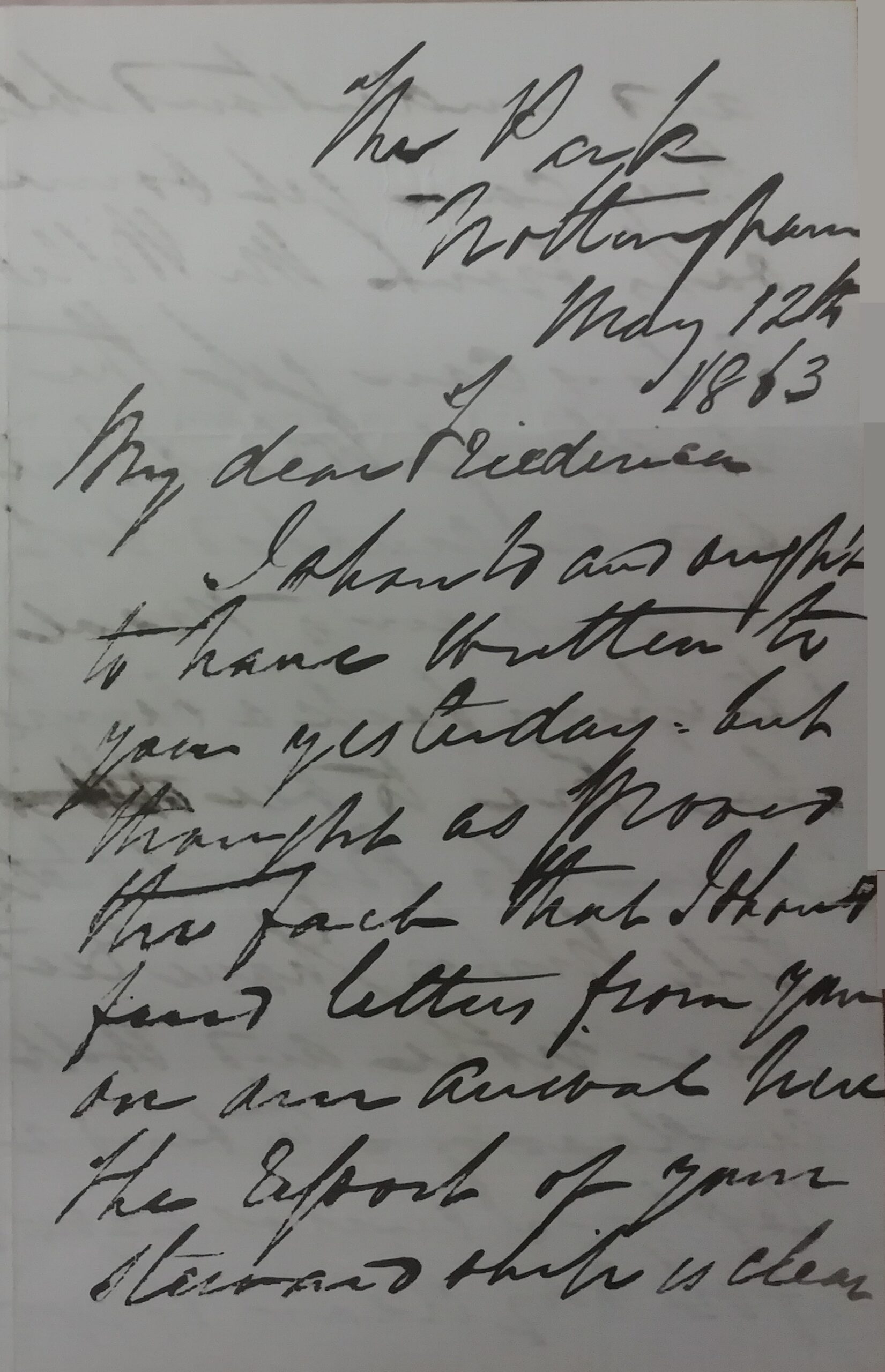

Frederica, like her sisters, was clearly well-educated and articulate. A surviving letter addressed to her from her father Robert in 1863 while he was away working in Manchester, mentions receiving her letters and apologises for not writing sooner.

The close relationship between Frederica and her father is further evidenced by the ‘Memorials of Robert Gill’ lovingly written and dedicated by Frederica in 1889.

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, June 1877.

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, June 1877.

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, undated.

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, undated.

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, undated. A note on the reverse reads: 'Aunt Friede, eldest daughter of Robert Gill and Fanny, nee Need.'

Carte de Visite of Frederica Gill, undated. A note on the reverse reads: 'Aunt Friede, eldest daughter of Robert Gill and Fanny, nee Need.'

Mary was born in 1849, in Mansfield Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire. At the time of her birth, her older sister Frederica was two years of age.

Sadly, we do not have as much direct source evidence from Mary’s life as we do for her other siblings. We can, however, assume that she was well-educated and brought up a devout Christian like her sisters, due to the evidence which remains of their lives.

Something that is clear is the close relationship between Mary and her siblings growing up. Numerous photographs and paintings depict them together, in tender poses which display their familial affection. In 1899, Mary accompanied her younger brother Robert John Seppings Gill on his visit to Beirut, Syria, in his capacity as an English Chaplain. The ‘Memorials’ book describes this as ‘an interesting experience’ for both, but unfortunately during the visit the pair became ill with typhoid fever and had to be nursed back to health in a German hospital there. Just 3 years later, Mary would become godmother to Robert John’s first child, Theodora.

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill, undated.

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill, undated.

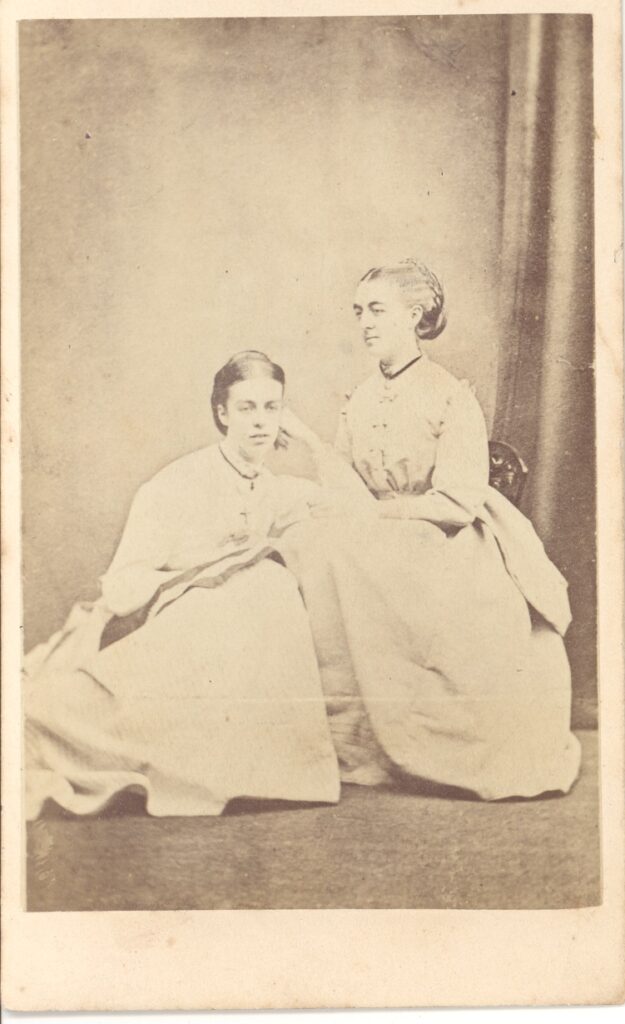

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill (left) with her younger sister Madeline Gill (right), c.1869-70.

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill (left) with her younger sister Madeline Gill (right), c.1869-70.

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill, c.1904-5. A note on the back reads 'Mary Gill E.M.G. with his love'.

Carte de Visite of Mary Gill, c.1904-5. A note on the back reads 'Mary Gill E.M.G. with his love'.

Madeline Lucy was the third daughter of Robert and Fanny Gill, and was born in 1852. She was just 3 years old when the family moved to Apps Court in Walton, and would spend the remainder of her life there.

Source records suggest that Madeline experienced a long-running illness. In ‘The Memorials of Robert Gill’, Frederica recalls that ‘she had specially been our father’s pet, and from her frequent absences from the schoolroom through ill health she was much with him and also used to be his companion on those evenings when Mother took Mary and myself out to parties, “my own Ma!” he called her’.

Madeline sadly died at Apps Court when she was just 17 years old, on 17th May 1870. Her family’s deep sense of grief at her early passing is explored later on in this online exhibition. The newspaper article announcing her death and describing her as a ‘dearly loved’ daughter was kept by the family.

Eleanor Maud Gill – more often referred to as simply ‘Maud’ by her family – was the first child of Robert and Fanny Gill to be born at Apps Court.

‘The Memorials of Robert Gill’ recalls that the birth of Maud was ‘a certain disappointment it was not a boy.’ Maud did not have long with her father before illness began to incapacitate him, and it is reported that as early as 1860 Robert started having ‘pain in his feet and then in knees as “creeping paralysis” spread upwards, and in the last few years so disabled him as to make walking even up and down stairs and to the hall door a great difficulty.’ Maud’s experience of life with her father must, therefore, have been vastly different to that of her older sisters, who remembered his energy during life at Mansfield Woodhouse.

Maud remained close to her family in later life, and was particularly devoted to her younger brother Robert John. She kept his house in Aldershot for him from 1893, eventually buying her own house, ‘Pine Holt’, in 1912 after the death of her mother.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in classical style costume, 1884.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in classical style costume, 1884.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in classical style costume, 1884.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in classical style costume, 1884.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in the late 1870s.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill in the late 1870s.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill, c.1888.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill, c.1888.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill, c.1904-5.

Carte de Visite of E. Maud Gill, c.1904-5.

Robert John Seppings Gill, a much yearned-for son, was born to his father’s ‘great satisfaction’ 4 years after the family’s move to Apps Court.

He was baptized locally, at the parish church in Walton, and was initially schooled privately by tutors in Brighton. In 1873, he begun his education at Eton, later attending the prestigious Magdalen College at the University of Oxford in 1878 – an opportunity none of his elder sisters received.

The younger Robert would not have known his father for long, with the death of the elder Robert Gill occurring when his son was just 11 years old. The ‘Memorials’ album recalls that Robert Senior, ‘in speaking of what he hoped and wished for his son’s future, expressed a kind of tender regret he should not live to see him grow up.’

The young Robert pursued a religious career after his education at the University of Oxford, being ordained as a Deacon in June 1882. His first Curacy was at Fordingbridge in Hampshire, and less than a year later in May 1883, he was ordained as a Priest. Robert John’s religious path could well have been shaped by his mother – Fanny came from a religious family, and the influence upon the young Robert of her grandfather William Welfitt (who was a notable Prebendary of Canterbury Cathedral) is clear in the naming of his first daughter – Theodora Mary Welfitt. Robert Senior’s religious devotion may also have influenced his son’s upbringing and subsequent career choice, with Frederica explaining in the ‘Memorials’ that ‘reverence was a strong feature in father’s character’, having also acted as a Churchwarden during his earlier life and made many improvements to his local Churchyard.

Robert appears to have been very close to his older sisters. Frederica Gill wrote the ‘Memorials’ for him, as an account of the life of the father he only knew for a short time. In later life, Frederica Gill also dedicatedly looked after her brother Robert’s vicarage and children on the occasions that he and his wife were away in London, bringing them up to visit their parents from time to time.

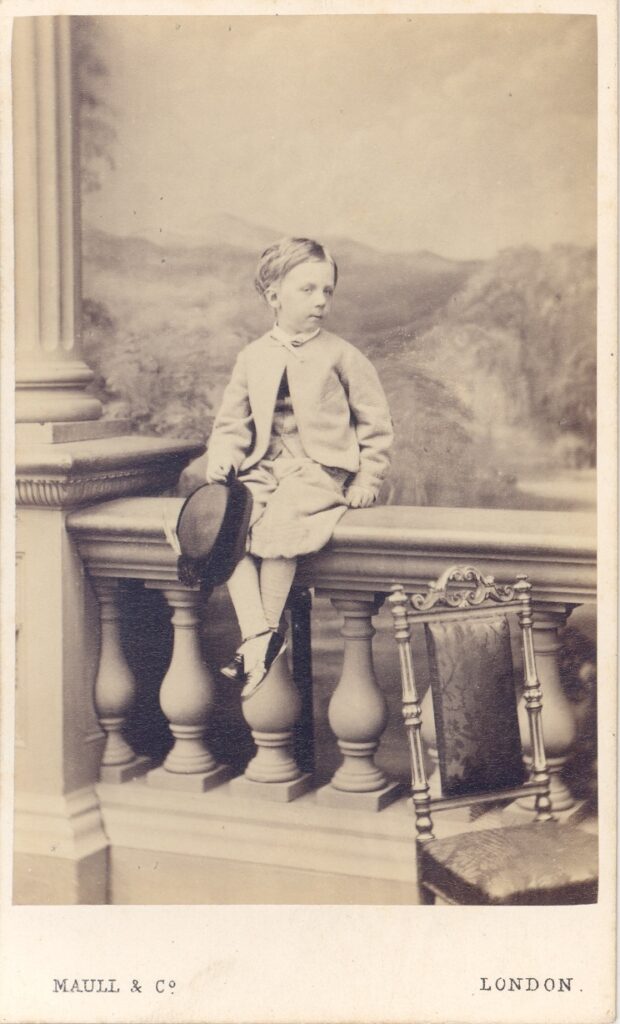

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill aged 4, seated on a balustrade, 1863.

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill aged 4, seated on a balustrade, 1863.

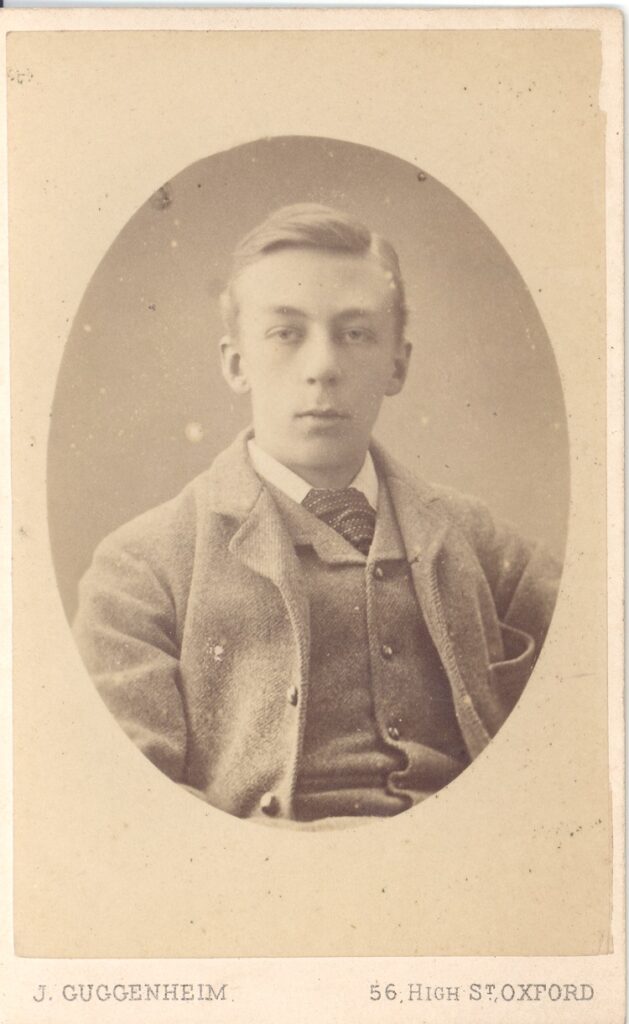

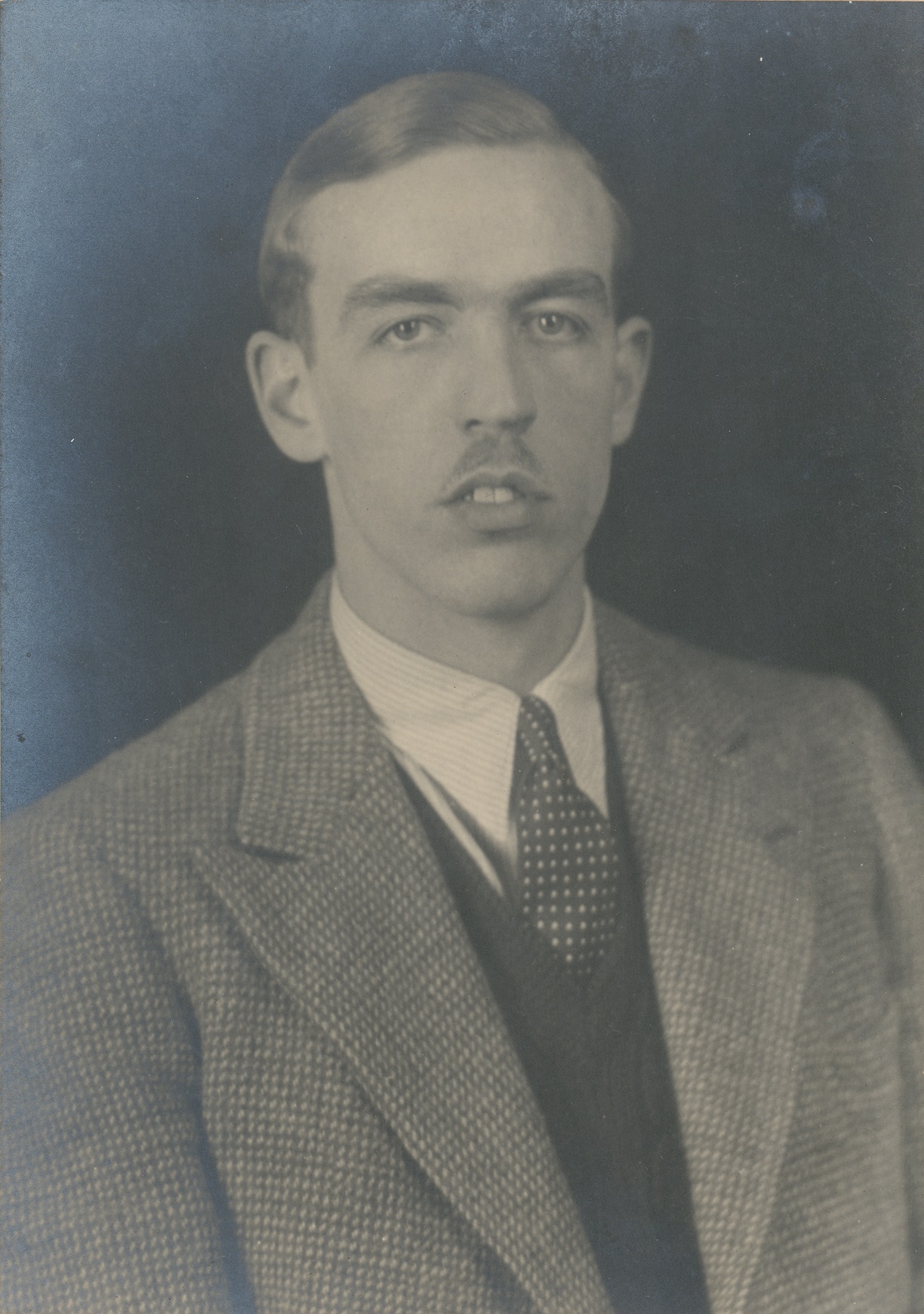

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill, 1879.

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill, 1879.

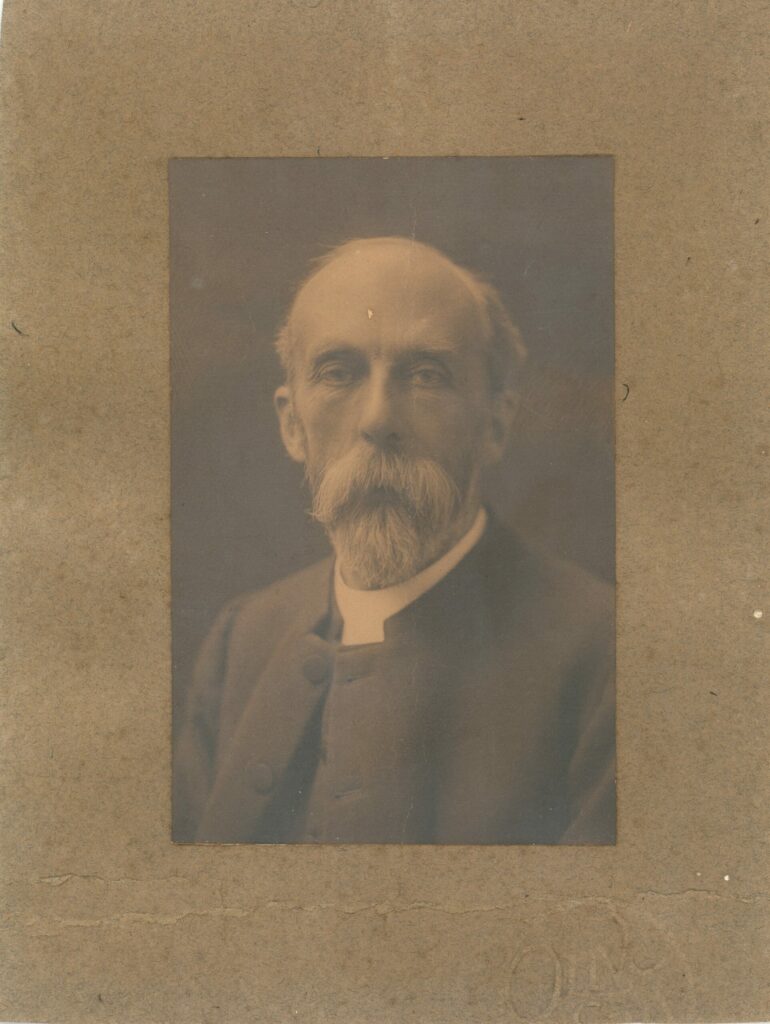

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill in old age, undated.

Carte de Visite of Robert John Seppings Gill in old age, undated.

Robert Gill had come from a long line of Gills of high status. His start in life was aided by the inheritance of £1000 from his father upon the latter’s death, and the already established family name was clear from a number of heirlooms bequeathed to him bearing Gill family insignia.

Robert Gill was able to build on this wealth throughout his career, starting out as a merchant and then involving himself in the railways, which, unlike many sceptics within his own family, he recognised as a scheme which would ‘revolutionize the whole world’. His vision and reputation after many successful years spent in the industry gained him the role of Director of the Great Western Railway of Canada, where he was swiftly promoted to Chairman of the English Board and President of the Canadian Board.

Robert Gill spent the great wealth he accumulated not just on his lavish family home of Apps Court, but on other projects such as The Palatine Hotel which proved to be a fruitful investment. He built it next to the Victoria Station in Manchester, and the original structure still stands to this day.

Gill had made his name through wise investment. He was as a result ‘constantly being consulted by promoters of works of public utility & requested to take part in them, and further by his energy and influence many of those inventions which at this epoch were furthering the march of Civilization.’ Such a successful and affluent life required equally luxurious possessions. The Gill family’s status is clear from the many bespoke items bearing the family’s initials and symbols, some of which are displayed below.

Four medallions of yellow glass are spaced around the outside of this vase. Three of the medallions are inscribed with pictures of horses, one galloping and two standing - reflecting the family's longstanding love of these animals. The fourth medallion is inscribed with the initials 'R.G', for Robert Gill. The 'Memorials' album recounts that this vase was given to Gill by the wife of Mr. Leo Schuster, a great friend. Mrs. Schuster had 'sad attacks of insanity' several times, and the 'Memorials' recalls that 'no one could manage to soothe her as well as [Robert Gill], and for hours he remained by her bedside.'

This small key-ring has two seals attached. These belonged to Robert Gill.

The seal intaglios are made from red agate, or similar stone, and are both set in frameworks of metal, each of a different design. One seal shows a lion rampant on the front of a shield. On top of the shield is a bird with outstretched wings. The other seal shows a rose, with a stem and leaves, and the Italian words "Cogliam La Rosa" (which literally translates as 'pick the rose').

This round silver salver has a decorative wavy edge and a London 1843 hallmark. The salver bears a crest often used by the Gill Family.

This piece of jewellery has both a pin at the back and a ring at the top for use as a brooch or pendant. The piece consists of a sheet of blue enamel with a pattern of dots and wavy lines showing through from beneath. The enamel is edged with a row of colourless, faceted, diamond-like stones. Upon the enamel are the initials 'J.N' created with similar, but much smaller, stones. We don't know who within the Gill family owned this piece, but its luxurious appearance and personalisation would have certainly displayed the wearer's wealth and status.

This silhouette shows Fanny Susannah Gill, in old age and wearing spectacles, in a metal oval frame. It is likely this was made after the death of her husband, Robert Gill.

The bases of these white wax busts are made of ebony and rose velvet, on a plinth of ebony. Robert Gill is depicted on the right and Fanny Gill on the left, her hair centre parted and swept behind her ears with plaits at the back. Both are in classical costume, a popular theme of the time. Each bust is attached to a round wooden plinth by a wooden dowel, and both have glass domes to protect them, which are not pictured.

This black and white colour-tinted oval photograph of Robert Gill rests within a brown leather-bound frame, with flaps on the front. The clearly much-treasured photograph would have been portable thanks to the protective flaps, which are seen closed in the image on the left.

This oil painting is by William Bradley, a prominent Victorian portrait artist. It was painted when Gill was aged approximately 35. We know that Gill commissioned the portrait himself, and that he subsequently commissioned a similar portrait to be painted by Bradley of his uncle, Robert Seppings, whose residence as Surveyor of the Navy was at Somerset House and who Robert Gill lived with from his late teenage years into his 20s. This painting shows Robert Gill from the waist up, leaning against a dark red chair and dressed in a black coat with high collar and two rows of gold buttons down the front.

This miniature portrait of Robert Gill's infant son is mounted in an oval metal frame set in a black wooden mount. When it is turned around, a handwritten note about the sitter can be seen on the back of the portrait.

Executed in pastels, this portrait is unsigned but believed to be by the artist C.A Duval. It depicts the heads and shoulders of Robert and Fanny Gill's second and fourth daughters, Mary (right) and Eleanor Maud (left). Mary's hand is on Eleanor Maud's shoulder.

Executed in pastels, the artist of this piece was C.A Duval, who signed and dated it 1858 in the bottom centre. It shows the heads and shoulders of Frederica Fanny Gill (left) and Madeline Lucy Gill (right), first and third daughters of Robert and Fanny Gill. The picture is fairly monotonal, with dark blue, black and brown as the predominant colours.

This press consists of two flat green boards held together by a beige canvas strap and a buckle. It formerly contained the photographs and carte de visite cards of the Gill family, helping to show how treasured these items were. The left image shows the press closed and the right shows it open.

These black and white photographs show Fanny Gill (left) and her son Robert John Seppings Gill (right) as a small child. Both photographs are in an oval mount within a black frame and covered in glass. They were possibly displayed in the Gill family home. Photography was still very new, and therefore expensive, in the early- to mid-Victorian era. Hence, these framed professional photographs are a sign of the Gill family's status and wealth.

This silhouette image is of Fanny Gill. Like the photographs, it is mounted in an oval metal frame and set in a black wooden mount. The black frame has an acorn in metal decorating the top. Silhouettes were cheaper to have made than going to a professional photographer, and therefore many Victorian families opted for silhouettes to depict family members instead. Although the Gills were wealthy and could clearly afford photographs, photography was still quite a new technology and not as readily available as it is now. This could be why Fanny opted for a silhouette rather than a photograph.

Miniature portrait of Madeline Gill in a gold coloured, oval frame. This may have been made as another memento in her remembrance after her death.

The Gill family’s story is punctuated by tragedy. Madeline Gill, the third of Fanny and Robert Gill’s four daughters, had suffered from illness throughout her life.

Sadly, on 17th May 1870 – a few months before her 18th birthday – Madeline suddenly died at Apps Court. The death was a shock to the whole family. Her sister, Frederica, wrote that ‘our dear Madeline was suddenly taken from among us – the first break in our immediate home circle.’ None felt the loss more keenly than Madeline’s father, Robert Gill. Frederica went on to write that ‘the shock of her death stunned him, and he could not always realise she was gone. He became visibly more failing in the autumn & on Friday 23rd December, the day before Christmas Eve the same year, he had a stroke and after a slight rally departed January 7th 1871’. He was buried in Walton Churchyard, in the same vault as Madeline.

Many efforts to remember Madeline were made by the family, in an attempt to deal with their grief. This beautiful gold locket is fronted by a cross of pearls. The inscription on the back reads ‘In Loving Memory of Madeline L. Gill, Died 17th May 1870, Aged 17’. When carefully prized open, a lock of Madeline’s blonde hair is revealed sitting inside the hollow centre.

Many consider the Victorian era to be one of suppressed emotion. Yet this locket of hair would imply otherwise. Although we don’t know which family member owned it, it does provide a tiny sliver of insight into this family’s intense and continued pain at losing a child so young.

Oval gold locket belonging to the Gill family. On the front is a cross formed by a narrow gold outline, lined with a layer of blue filled with twelve pearls.

On the back of the locket is the inscription – ‘In Loving Memory of Madeline L Gill, Died 17th May 1870, Aged 17.’

The inside of the locket contains a lock of Madeline Gill’s hair.

There are many other examples of how the Gill family coped with loss and demonstrated their strong emotions and love for one another. Explore them below.

A letter from Robert Gill to his daughter Frederica, dated 12th May 1863.

A letter from Robert Gill to his daughter Frederica, dated 12th May 1863.

The Victorian era is often seen as one in which women were downtrodden and treated with little respect – and in many instances, this is true. Yet although Robert Gill was the breadwinner in his family and clearly the head of the household, there was an undeniably strong female influence in his earlier years which clearly affected his attitudes towards the women in his life.

Robert had been brought up by his grandmother, Ann Gill, whom he remembered ‘with affectionate veneration, describing her as a little but dignified old lady, who wore black velvet shoes and leant on a gold headed stick. She was very pious, and her voice often overheard by him repeating her private prayers aloud in her bedchamber.’

He showed a similar veneration and respect towards his mother-in-law, Mrs. Need, who ‘lived in the house whose garden adjoined the kitchen garden’ during Robert and Fanny’s life at Mansfield Woodhouse. Robert was ‘extremely attached’ to Mrs. Need, with the old lady regularly being wheeled between the houses through a doorway made in the fence.

This female influence continued in Gill’s later life with his four daughters. In Elmbridge Museum’s collection, there survives a letter from Robert Gill addressed to his eldest daughter Frederica in 1863. The affection expressed in the letter by Robert is a clear signpost of his close relationship with his wife and daughters.

Eleanor Maud Gill, youngest daughter of Fanny and Robert Gill, photographed c.1880s reading a book.

Eleanor Maud Gill, youngest daughter of Fanny and Robert Gill, photographed c.1880s reading a book.

The Gill daughters were intelligent and literate, as these were qualities their parents saw as important. Although it was not unheard of for girls to be well-educated in the Victorian era, females often left school at the age of ten, whereas males continued on into secondary education.

Many in Victorian society laid emphasis on the domestic roles women were expected to fulfil, and their training as good wives and mothers often took precedence over academic learning. This attitude towards women is evident in a letter written to Fanny Gill from Mr Goodacre, the Pastor of their old parish. He wrote to Fanny after hearing of the family’s move to Apps Court, and the original letter survives in the Museum collection. In it, he thanks Fanny for the help she provided to the poorer parishioners, but also makes several references to her role as a mother. He writes that ‘there are certain maternal duties which cannot be delegated nor should any attempt be made to do so’, and prays that Fanny’s children ‘may be a comfort to you in their childhood’.

Read the original letter in full here.

Evidence in the ‘Memorials’ album suggests that Robert Gill had a very different attitude than most towards the education of women. His daughter Frederica recalled that ‘he always urged us to acquire knowledge and so make it our own as to be capable of teaching the law to others if need be, and assured us the ups and downs of fortune were such no lady could or should feel she might not have to earn her own living some day.” Perhaps this progressive attitude was why, despite a fall-out with his brothers in earlier life, he had still generously paid for his nieces Ann and Mary Gill to be sent to school.

The items below, including books, photographs and handwritten documents, all help to demonstrate the keen literacy of the Gill daughters.

The Pietas Quotidiana was a collection of ‘prayers and meditations for every day of the week and on various occasions being a collection from the most eminent divines and moral writers.’ It was given to Madeline Lucy Gill at her first Communion, with the written inscription 'M.L.G's first Communion, Sunday April 11th 1869.' The image on the first page shows a man on his deathbed being visited by an angel, while his family mourn by his bedside and an hourglass lies knocked to the floor. The caption reads 'Say unto my Soul "thy sins be forgiven, depart in peace".' The book not only demonstrates Madeline's literacy, but is also a poignant reminder of her early death - and perhaps suggests that religious belief may have been a comfort to her grieving family.

This copy of 'Silas Marner' by George Eliot contains a touching handwritten note from Fanny Gill to her daughter, which reads 'Frederica Fanny Gill, New Year 1877, from her mother F.S Gill'. George Eliot's real name was Mary Ann Cross, and although female authorship was rare in the Victorian era, she published 7 popular novels. We know that Eliot was widely read by the Gill family - in the 'Memorials' album, Frederica notes that her father liked being read to 'and appreciated the clever articles in the "Saturday Review"... but did not like "Mill on the Floss".' This was one of Eliot's most famous novels published in 1860, just a year before 'Silas Marner'.

There is perhaps no better illustration of the Gill daughters' literacy than the album written by Robert Gill's eldest daughter, Frederica, and dedicated to her younger brother Robert John Seppings Gill in January 1889. The huge album recounts in handwritten prose the life of Robert Gill, a clear sign of Frederica's intelligence and learning.

If a written album was not enough to demonstrate the good education of the Gill children, there are many photographs which express this too. This photograph of Frederica Gill shows her sitting at a writing desk, pen poised above the paper. The whole image is staged as though she has been interrupted in the middle of this activity, telling the viewer she is an intelligent, upper-class women for whom writing was a standard daily activity. With this image, it is easy to also visualise Frederica sitting to write the 'Memorials'.

A photograph of Apps Court and the surrounding estate in 1894, just 3 years before Fanny Gill moved out of the property and 4 years before it was sold the the Southward and Vauxhall Water Company, who demolished it.

A photograph of Apps Court and the surrounding estate in 1894, just 3 years before Fanny Gill moved out of the property and 4 years before it was sold the the Southward and Vauxhall Water Company, who demolished it.

After Robert Gill’s death, his widow Fanny continued living at the family home with her daughters. By 1897, however, with her children by this time grown up, Fanny finally left Apps Court, settling in ‘The Red House’ in Yateley, Hampshire, where she died in August 1911 aged 93.

Before Fanny left, a large amount of the land on ‘Apps Court Farm’ next to Apps Court had been bought by the Chelsea Water Company. The ‘Memorials’ album recounts that ‘an avenue of beautiful old birch trees’ on this site were cut down in 1875 when the Company acquired the land. On the same site, there had also been an old chapel called ‘Cardinal Wolsey’s Chapel’ – said by contemporaries to have been haunted by the ghosts of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn – which was likewise pulled down around this time.

A year after she left, Fanny Gill sold the property of Apps Court to the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company in 1898. The Company soon destroyed the old Georgian house to make way for the two reservoirs which still stand on the site today. During the first few years of the 1900s, many treasures were excavated here while the demolition and building work was taking place, including a number of Elizabethan coins.

Before she died, Fanny lived to see the family name continue through the births of her grandchildren.

Her only son, Robert John Seppings Gill, met his wife Mary Williams when working at Holmwood, Surrey, as a vicar. The couple were engaged in April 1901 and married later that year on 6th August. The couple had 4 children: Theodora Mary Welfitt Gill (born 1902), Madeline Frances Gill (born 1904), Katherine Margaret Gill (born 1908) and Robert John Brooke Gill (born 1911).

Out of all of the Gill grandchildren, we know the most about Robert John Brooke’s life – referred to simply as ‘John’ by the family. He was born in Frensham, Farnham, where his parents then lived, on 11th February 1911 – just 6 months before his grandmother died. John’s mother added a note at the back of the ‘Memorials’ album, that on the day of his birth ‘the bells of Frensham Church rang out merrily after the 8am Celebration in honour of the occasion!’

Click through the following pages to explore paintings and photographs of John throughout his life.

A framed oil painting portrait of Robert John Brooke Gill (known as John) in 1913, aged 2, shown seated on a wooden chest. Behind him is the head of a toy horse, and he holds a riding whip and a piece of red cloth.

A framed oil painting portrait of Robert John Brooke Gill (known as John) in 1913, aged 2, shown seated on a wooden chest. Behind him is the head of a toy horse, and he holds a riding whip and a piece of red cloth.  A black and white photograph of Robert John Brooke Gill (known as John), taken sometime in the 1940s when aged in his 30s.

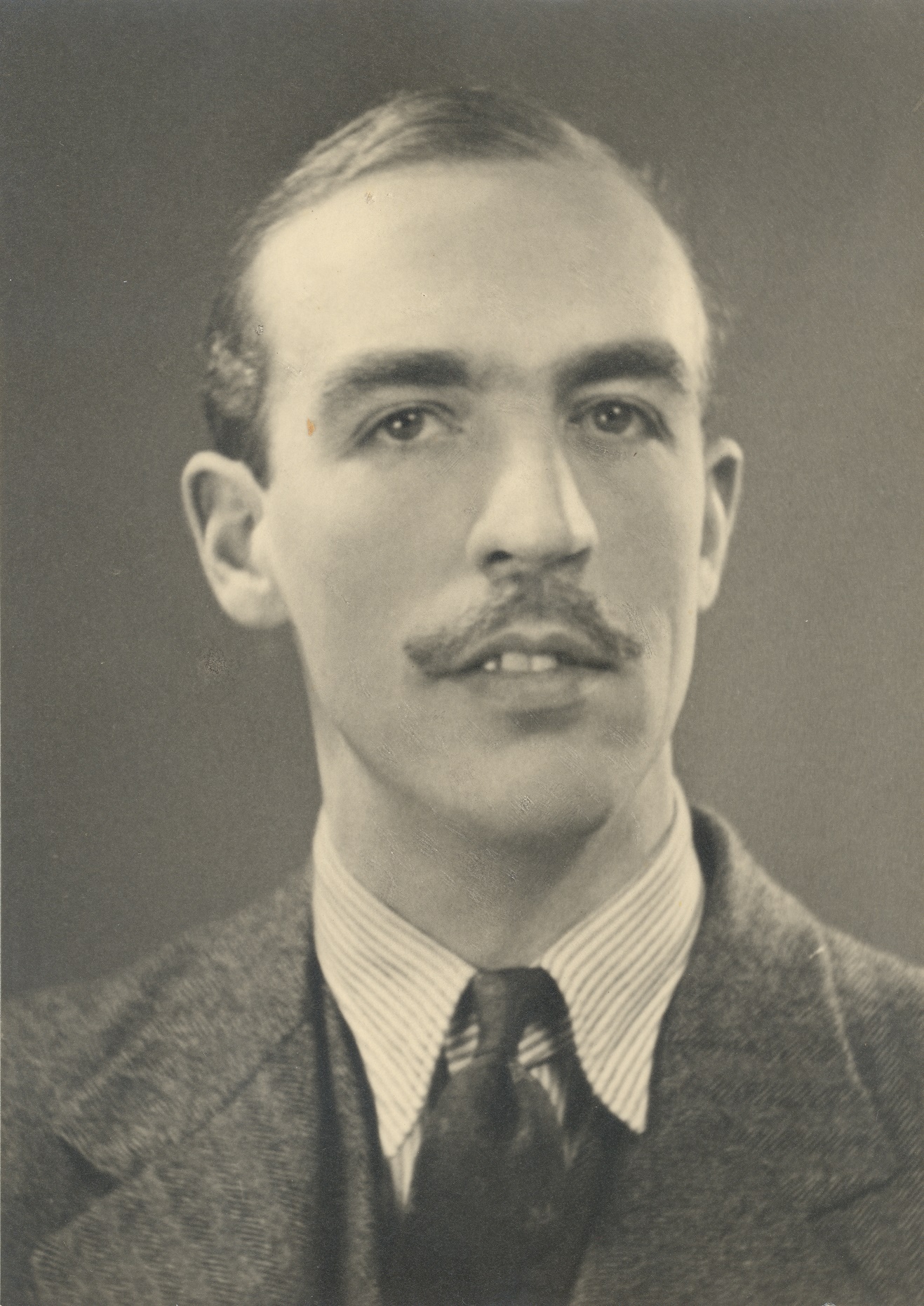

A black and white photograph of Robert John Brooke Gill (known as John), taken sometime in the 1940s when aged in his 30s.

A black and white photograph of Robert John Brooke Gill (known just as John), taken in the late 1940s when he was in his late-30s.

A black and white photograph of Robert John Brooke Gill (known just as John), taken in the late 1940s when he was in his late-30s. Want to learn more about the famous Victorian racecourse neighbouring the Gills at Apps Court?

Our online exhibition, 'A Day at the Races', explores the history of Hurst Park racecourse, an extremely popular track just down the road from Apps Court, which attracted thousands of high society visitors from its opening in 1814.

Leave a Comment

We'd love to know what you thought of this online exhibition, or if you have your own memories of the Apps Court area.A most interesting exhibition, however I am researching Apps Court from a hundred years earlier, from 1718, when my ancestor James Brand may have been bailiff, in the era when it was owned by the Montague family. At present I am trying to fill in the details of the estate and life there from 1718 to 1742 and afterwards. Do you have any material from that time? I have a little from the Surrey History Centre, and am currently transcribing some early legal \"deeds\". (Re later times, I also have some TNA photos of the house being demolished for the water company!)

Hi Robin,

Many thanks for your feedback, we’re really pleased you found this online exhibition interesting. We have sent you an email about your enquiry into Apps Court in the 1700s.

Best wishes,

Elmbridge Museum team

You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register