Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Postcard of the Schiff Home of Recovery, Cobham, showing interior of ward with adults and children, nurses and a doctor.

Postcard of the Schiff Home of Recovery, Cobham, showing interior of ward with adults and children, nurses and a doctor.

Throughout history, sickness and health has played a huge role in shaping personal, national and international narratives. Keeping well was, and still is, important to most people, and local history shows how they constantly interacted with healthcare.

‘Traditional’ healthcare might evoke hospitals, local surgeries, white coats and stethoscopes. But when we consider the overall impact the topic has had on local people, it becomes much more expansive. In this display, we explore how health has interacted with:

Each section paints a picture of the myriad ways sickness and health has always interwoven with daily life here in Elmbridge.

From the prehistoric era, medicine and health would have played a huge role in everyday life. Early death was common and often caused by malnutrition, unsanitary conditions, or diseases which we can easily treat with modern medicine today. Without an organised healthcare system, much healthcare was carried out by local physicians or healers in the home, and, at a time when biological science was still vastly shrouded in mystery, understandings of health were closely tied to spiritual and religious beliefs. The role of religion in health and wellbeing has, however, not completely vanished – in many instances, it has persisted to the modern era as a comfort to those facing illness and death.

Bronze Age bottle in unglazed light terracotta earthenware

This piece of earthenware is known as an unguent bottle, and it would have been used in a Bronze Age home for storing medicine. It is thought to have been made in Cyprus. Bronze Age medicine was often derived from naturally occurring substances such as plants and clay, with recent research suggesting it was far more advanced than once believed.

Rim of a red-dipped Roman mortarium, excavated c. 1942

Mortariums were Ancient Roman kitchen vessels used for mixing. They would have been important, not just for cooking, but also for the mixing of medicines and remedies. Different herbs and plants were mixed by people in the home to cure diverse ailments, including birthwort for assisting in childbirth and aloe for wounds and boils, which we still use today.

This mortarium sherd was found in Cobham, on the site of Chatley Farm Roman bathhouse. As well as being a social activity, visiting the bathhouse itself was intrinsically linked to good health for the Romans. Bathing was often prescribed as a treatment, particularly for recuperating soldiers, and it was recognised that the warm waters could have benefits for circulation and muscular problems. Occasionally, though, the more humble bathhouses may have themselves harboured diseases and bacteria, with roundworm and other parasites posing a particular problem if the water was not changed regularly enough.

Find out more about Chatley Farm Roman Bathhouse

Part of an Iron Age circular stone rotary quern

This thick circular slab would have been used for grinding corn. This was the top of the quern, and it would have rested on top of a thicker slab of stone. Corn was dribbled through the hole in the centre and the stone turned by a wooden handle wedged to the cut segment, the flour would then be ground between the two stones and fall out around the edges.

Diet was recognised as playing an important role in health in prehistory. Quern stones were been used by a number of ancient civilisations and cultures across the world to create flour for bread, but Iron Age diets were actually incredibly varied and healthy. For example, the people living at the Iron Age hillfort at St. George’s Hill (excavated in 1911) would’ve included farmers, as well as hunters and gatherers. Their proximity to the River Thames and rich hunting ground would’ve meant their diets were rich in fish and red meat, with root vegetables also grown in the fertile soil and eggs and meat from livestock reared within the fort.

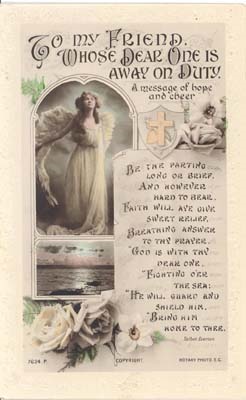

War postcard ‘To my friend whose dear one is away on duty’, c. 1914-18

Prayer and religion have always been closely interwoven with ideas about health and wellbeing, and this is particularly evident in times of precarity. From thousands of years ago, it was believed that ill health or fortune was linked to divine punishment and disapproval, and that prayer to God could offer protection or help to heal the sick. Despite the gradual secularisation of society as understandings of health science became more advanced, the First World War of 1914-18 still saw an explosion of religious messaging.

This postcard, sent to a local resident whose loved one was fighting in the First World War, reassures the recipient that ‘God is with thy dear one, fighting o’er the sea: He will guard and shield him. Bring him home to thee.’ It indicates the helplessness that family at home may have felt in the face of the heavy toll of sick, dead and wounded soldiers: prayer was one of the only ways many thought they could help to protect their loved ones from these incredibly prominent dangers.

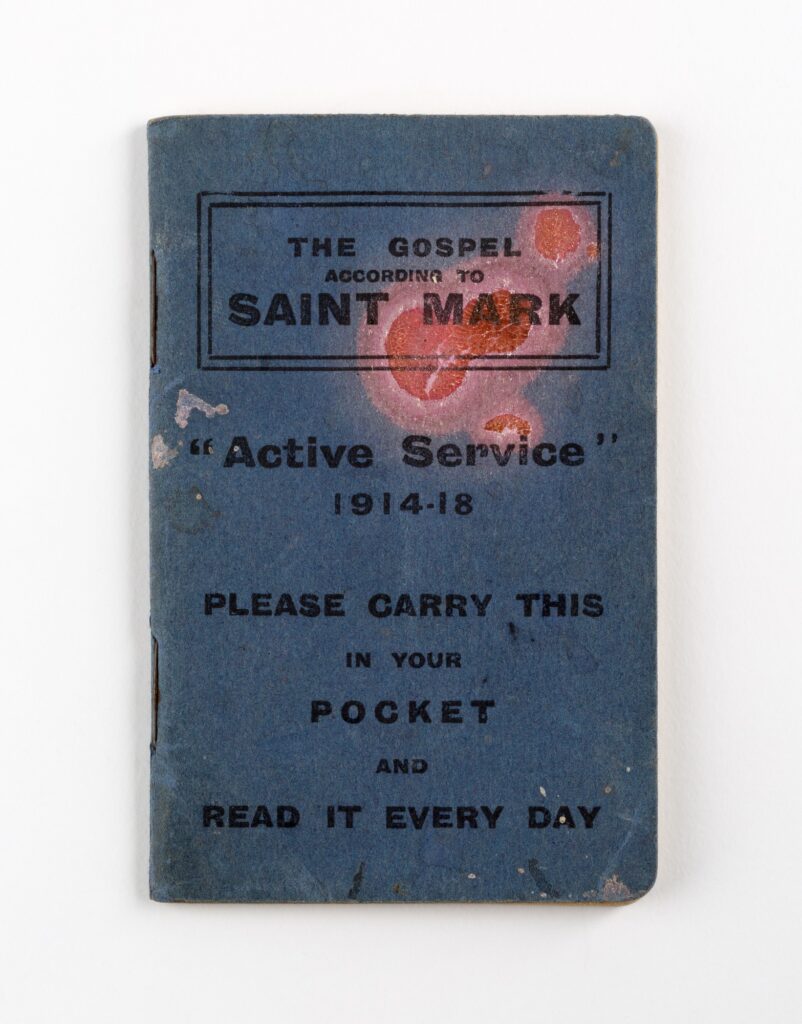

Image 1: Booklet of ‘The Gospel according to Saint Mark’, c. 1914-18

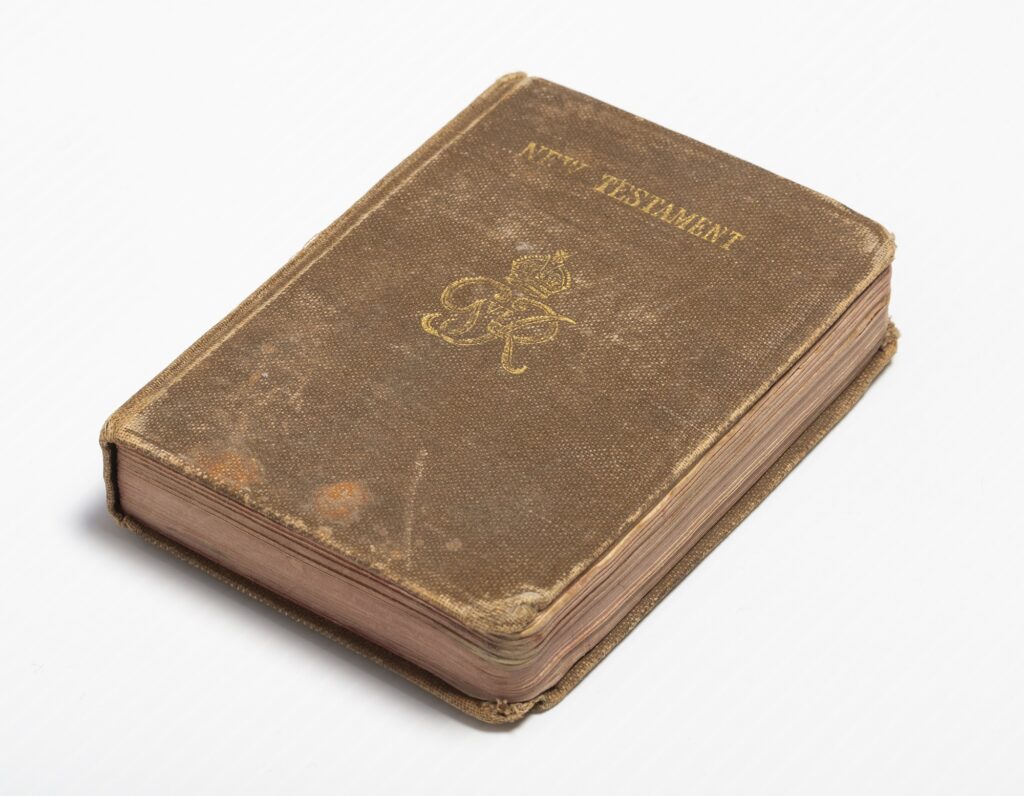

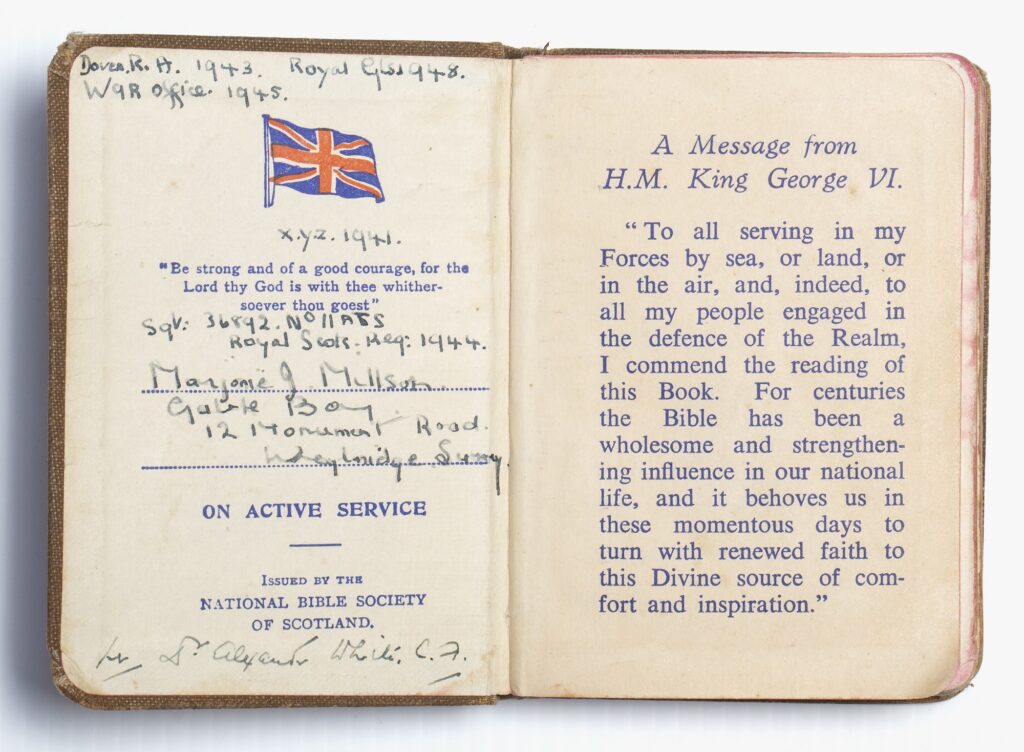

Images 2 – 3: Pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, c.1939-45.

These booklets were created for those on active service during the First and Second World War. The blue First World War booklet carries an instruction to ‘Please carry this in your pocket and read it every day.’

The first page of the brown Second World War booklet contains a message from King George VI about seeking divine comfort and reassurance from the text. This booklet was used by Marjorie Millson, who formerly lived in Monument Road, Weybridge, and was attached to the Royal Scots Regiment, The War Office, and other official bodies during the Second World War.

Like the postcard, both booklets demonstrate the enduring power of religion as a comfort to those facing potential harm or death: they offer recognition that prayer at the very least could boost morale and mental wellbeing, and at most could ensure divine protection of the physical body.

Booklet of ‘The Gospel according to Saint Mark’, c. 1914-18.

Booklet of ‘The Gospel according to Saint Mark’, c. 1914-18.

Pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, c.1939-45.

Pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, c.1939-45.

Inside pages of the pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, c.1939-45.

Inside pages of the pocket-sized edition of the New Testament, c.1939-45.

Gold mourning ring, 1670

Where ill health resulted in death, we see religion yet again playing an important role throughout history. This gold ring was discovered using a metal detector, close to the bridleway that leads from St. Michael’s Chapel, Downside, to Downside Mill and Downside Farm. It bears the inscription ‘Prepare to follow F.V’ and the date ’16 May 70’, relating to Sir Francis Vincent of Stoke D’Abernon.

Francis was the second husband of Mary Bigley, whose family had been bailiffs of the manor of Cobham for Chertsey Abbey before its dissolution in 1537, after which they bought the manor from the Crown. Francis died in the morning of 16th May 1670. In his will, he made large bequests to various family members to ‘buy them rings’, and on this one we see a skull engraved on the exterior.

Mourning rings were common in the early-modern era, often distributed at funerals to remember loved ones who had passed, but equally serving as a constant reminder to the wearer of the proximity of death, something particularly resonant in a society where everyday ailments could pose very real dangers and death could be around the corner at any moment.

Read about Elmbridge Museum's acquisition of the mourning ring in 2019 Gold mourning ring, 1670

Gold mourning ring, 1670

Detail of a 17th century gold mourning ring discovered in Elmbridge in 2008.

Detail of a 17th century gold mourning ring discovered in Elmbridge in 2008.

Oval gold locket containing a lock of hair, 1870

Much like the mourning ring, this locket (dating 200 years and one day later) again would have offered comfort to family members upon the death of a loved one. On the back of the locket is the inscription ‘In Loving Memory of Madeline L Gill, Died 17th May 1870, Aged 17.’

Madeline was the third daughter of Robert and Fanny Gill, who lived at Apps Court, in Walton. She had reportedly suffered from illness from an early age, rendering her frequently absent from the schoolroom. As a result, she spent much time with her father Robert, and indeed the shock and stress of her death may have played a part in bringing about his stroke and subsequent death just 8 months later.

The locket containing Madeline’s hair offers a glimpse into past illness and mortality, as well as giving us an idea of how Victorian society coped with early death. The cross pattern on the front, lined with a layer of blue filled with twelve pearls, also hints at the prominent role still played by religious belief in coming to terms with sickness and death at this time.

Read more about the Gill family's story here Oval Gold locket belonging to the Gill family. On the front is a cross formed by a narrow gold outline, lined with a layer of blue filled with twelve pearls.

Oval Gold locket belonging to the Gill family. On the front is a cross formed by a narrow gold outline, lined with a layer of blue filled with twelve pearls.

Oval Gold locket belonging to the Gill family. On the back of the locket (top right) is the inscription - In Loving Memory of Madeline L Gill, Died 17th May 1870, Aged 17.

Oval Gold locket belonging to the Gill family. On the back of the locket (top right) is the inscription - In Loving Memory of Madeline L Gill, Died 17th May 1870, Aged 17.

The inside of the oval gold locket containing a lock of Madeline Gill's hair.

The inside of the oval gold locket containing a lock of Madeline Gill's hair.

Pharmacies have historically provided local people with access to various remedies, cures, and later on, drugs – either to treat mild illnesses or dispensing stronger medication prescribed by doctors. The first pharmacies and trade in medicines in England emerged in the 1100s, with trade regulated by the Guild of Pepperers who were responsible for regulating the industry. Eventually, the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries founded by James I replaced them in 1617. The Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain became the regulatory body from 1841, controlling the registration and operation of pharmacists and pharmacies across the UK and overseeing the development of pharmacies and chemists into the organisations we are familiar with today.

Until recently, women have traditionally been written out of historical narratives and faced several barriers to working on the same terms, in the same jobs, as men. Nursing, however, is one area in which women have almost always been historically present. Evidence for the involvement of women in healthcare, both formally in hospitals and informally in the home and as local healers, spans centuries. We can demonstrate through items in the Museum collection how local women stepped up to assist casualties in times of national crisis, and we can also trace how understandings of female health itself, once murky and poorly researched, have evolved over time.

Opinions on middle-class women working were generally unfavourable at the turn of the 20th century, and there were only around 300 female nurses. Attitudes, however, markedly shifted on the advent of the First World War from 1914-18. During this time, and particularly from the introduction of conscription for men into the army in 1916, it was necessary for all classes of women to take on both voluntary and paid work, often adopting roles traditionally occupied by men. There was a great need to recruit women into the nursing profession in particular. Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) were essential in aiding the treatment of the vast number of wounded soldiers. VADs would not carry out the full extent of the work of trained nurses – many of whom were sent to the front line to treat badly wounded soldiers – but would often be found running local auxiliary hospitals like Mount Felix War Hospital in Walton. The result was that by the time the war ended, the profession had grown to encompass 10,000 women.

The postcard here shows a Belgian Red Cross nurse treating a wounded soldier on the battlefield, and the caption literally translates as ‘The Good Star of our Wounded’. It demonstrates how nurses were presented as saintly figures who were prepared to risk their own safety to help and protect soldiers in need, an image which had begun with that of Florence Nightingale as ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ during the Crimean War less than 70 years before. Around 1,500 nurses from across all participating countries died while serving in the First World War.

The British Red Cross was formed in 1870, primarily to provide aid to the sick and wounded of war. From 1907, the organisation set up local branches across the country, and the Voluntary Aid Detachment scheme followed on in 1909. Red Cross volunteers were essential across both the First and Second World Wars, in the latter joining up with the Order of St John to help people during the Blitz, drive ambulances, find missing people and despatch supplies to British prisoners of war. These medals were all issued to Molly Jack, who served with the British Red Cross during the Second World War. She was a committed member, completing training in home nursing and first aid to the injured. We know she stayed with the organisation for at least 3 years, evidenced by her 3 years’ service medal. Molly was an active member of the community, owning a shop in Walton High Street and becoming heavily involved in local arts and drama as the Chair of the Drama Festival Committee in the 1970s. She experienced both sides of the war, both helping the injured and sadly having her own shop bombed during the Blitz.

During the First World War, women were encouraged to volunteer as nurses. Even upper class women, who may not previously have been employed, were eager to contribute to the war in this way, and even high-profile people such as the Princess Mary, daughter of George V, took it up. The front of this magazine states that Mary was a 'ministering angel' and that 'during the War she learned the art of nursing at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children'. Her work as a Red Cross nurse leads the magazine to state that she 'has been trained in service since her earliest days'. Women like this inspired many other women to enter the nursing profession during the war.

A British Red Cross Detachment with nurses, health visitors, commandants and doctors in the Locke-King clinic, 1946.

A British Red Cross Detachment with nurses, health visitors, commandants and doctors in the Locke-King clinic, 1946.

A huge number of other local voluntary and professionally trained nurses assisted at the Locke King Clinic in Weybridge during the Second World War, photographed here around the same time.

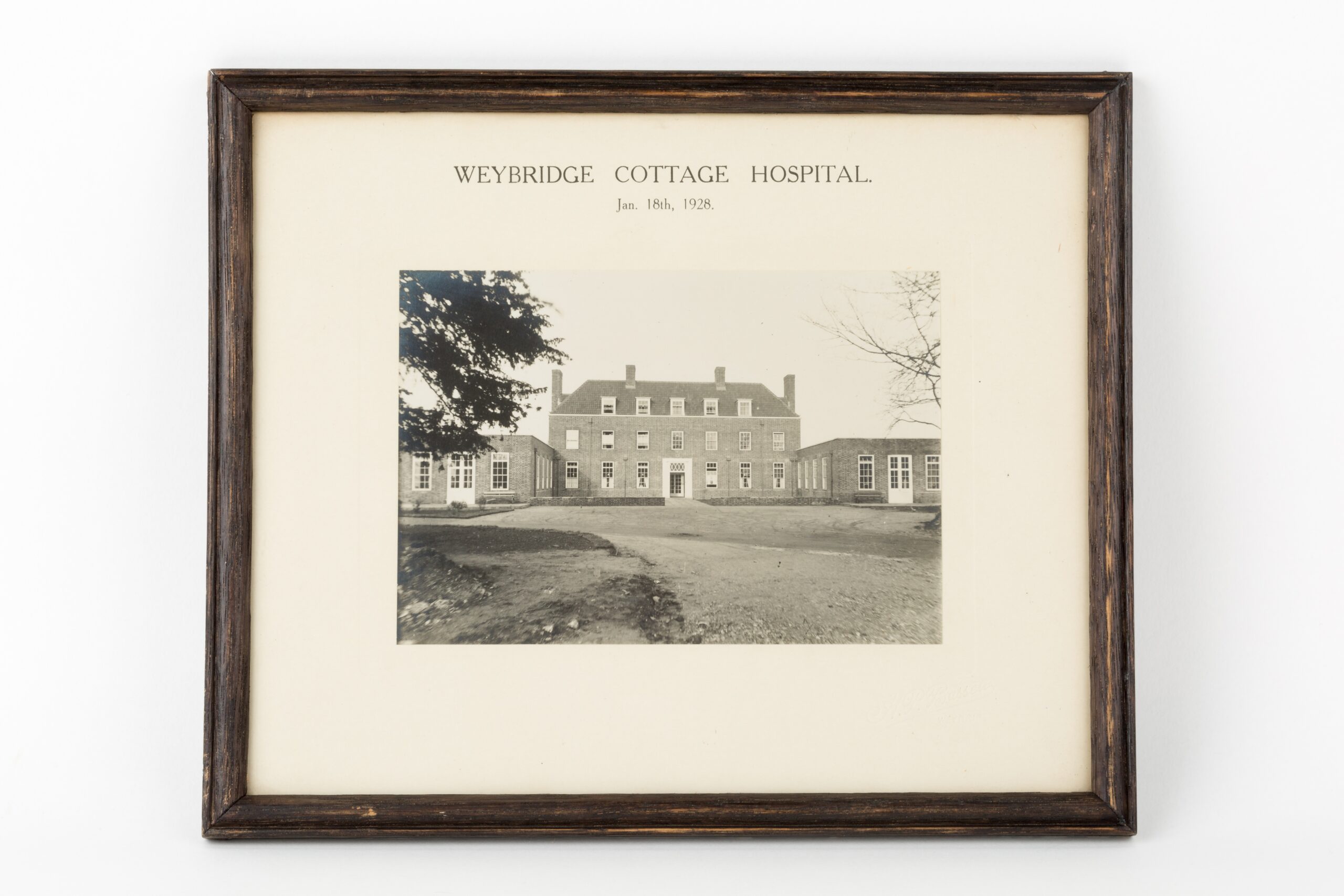

The Locke King Clinic had started as Weybridge Cottage Hospital in 1889, situated in Balfour Road, and moved to a new, larger site in Church Street in 1927-8 thanks to the funding of Hugh Locke King and was renamed Weybridge Hospital. Hugh’s wife, Dame Ethel Locke King, had notably run 15 military hospitals for the Red Cross in the First World War and managed 19 VADs encompassing 700 volunteer nurses as part of this. An already prominent local figure, in 1928 she bought the old Balfour Road Cottage Hospital building and gifted it to the new hospital’s trustees. This building was repurposed as an extension to the services offered by the main Weybridge Hospital, and was named the Locke King Clinic in Ethel’s honour.

Although fairly small, the Locke King Clinic was essential to locals during the 1940 German bombing raid on the Vickers-Armstrong aircraft factory at Brooklands, acting as the first port of call for ambulance drivers transporting those injured to be treated, where nurses worked from about 2pm right through the night and into the morning. The beds of the 75 in-patients filled the wards and corridors, and the capability with which the nurses handled the situation was later formally recognised by the Home Office.

The Locke-King Clinic closed in 1986-87, and is now known as Locke King House, serving as both offices and a menopause clinic. In 1992, the main hospital in Church Street was facing difficulties meeting local demand for its services, and so a new Weybridge Community Hospital was build adjacent to the old one in 1999, with the old buildings being demolished. A fire in 2017 destroyed this building.

A ward inside the main Weybridge Cottage Hospital, Church Street, showing patients in beds and nurses in uniform. It was donated by a nurse who worked at the hospital during the Second World War. Undated but post-1928.

A ward inside the main Weybridge Cottage Hospital, Church Street, showing patients in beds and nurses in uniform. It was donated by a nurse who worked at the hospital during the Second World War. Undated but post-1928.

Framed black and white photograph of the front view of the new Weybridge Cottage Hospital, Church Street, 1928. It was donated by a nurse who worked at the hospital during the Second World War. Undated but post-1928.

Framed black and white photograph of the front view of the new Weybridge Cottage Hospital, Church Street, 1928. It was donated by a nurse who worked at the hospital during the Second World War. Undated but post-1928.  The Locke King Clinic at Balfour Road junction, 1984.

The Locke King Clinic at Balfour Road junction, 1984.

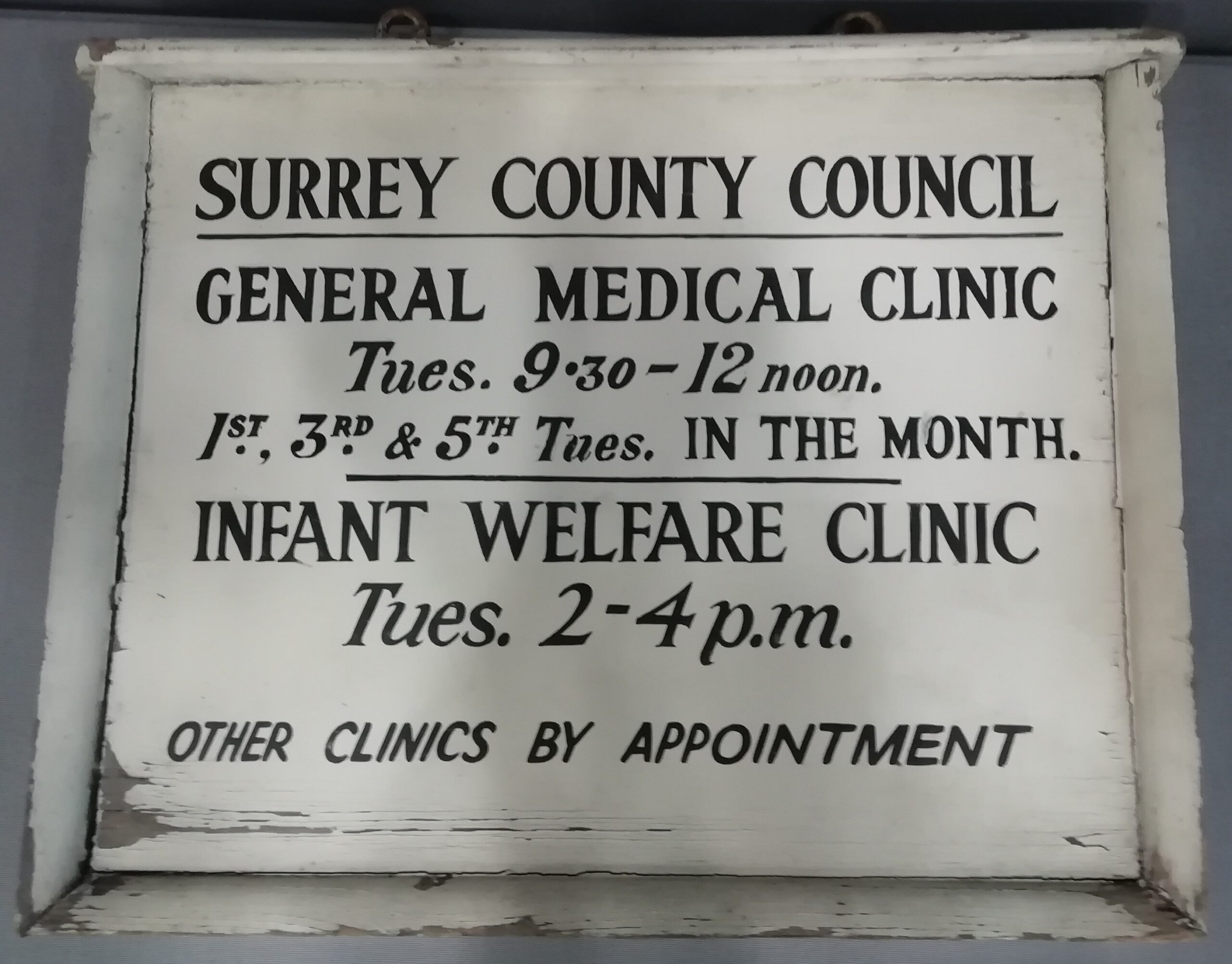

Sign removed from Locke-King Clinic after its closure in 1986-87.

Sign removed from Locke-King Clinic after its closure in 1986-87.

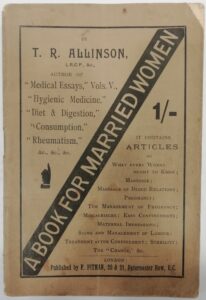

Although women were gradually entering into healthcare in the early 1900s, understandings of female health were still heavily tied to outlooks on their place in society and role in the home. The ‘Book for Married Women’ here demonstrates in the title alone how knowledge of female health topics such as pregnancy, childbirth and fertility were only considered appropriate for women who were married – detailed information on the workings of the female body was often kept hidden from younger, unmarried girls.

The book’s author, Thomas Allinson, was a physician and vegetarian activist who is often remembered as the first advocate for wholemeal bread. Despite the title of this book and some of the traditional attitudes around marriage it encouraged, the book was actually considered very scandalous at the time of its publication for the way it supported equality between women and men and argued for the rights of women to choose the size of their family through birth control. As a result, Allinson was prosecuted and convicted under the Obscene Publications Act in 1901.

“For a young man under thirty to marry a woman over forty is a mistake, for he cannot expect to have any children, and thus the natural meaning of marriage is frustrated… Delicate and deformed persons may safely marry on the condition that they do not attempt to reproduce their kind, but use positive checks to prevent conception.” – T.R. Allinson on ‘Marriage’, in ‘A Book For Married Women’, 1894.

Allinson advocated for contraception because of his belief that if ‘weak’ people could prevent themselves from reproducing, it would mean only ‘strong’ children would be born and that this would be “the best course for humanity”. The more widespread introduction of contraception, however, would have far greater consequences for female health and quality of life. As a result, some women from the early 20th century began to expand their horizons – contraception made it more possible for them to pursue both a career and a romantic relationship at the same time, with a greater degree of control over when they had children, and how many they had.

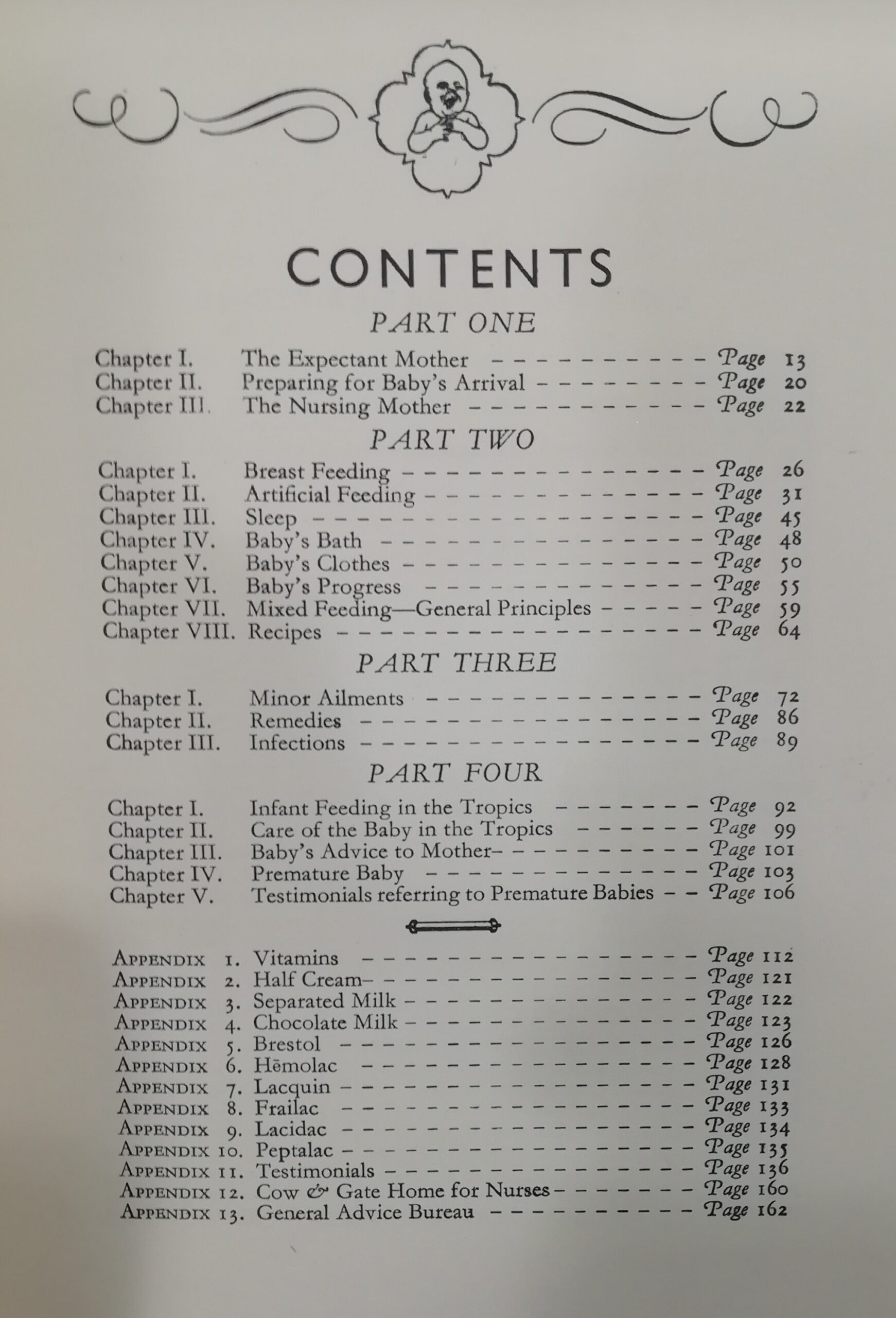

The Cow & Gate ‘Guide for Mothers’ shows how some attitudes had progressed by the 1930s. The book covers topics such as ‘The Expectant Mother’, ‘The Nursing Mother’ and ‘Baby’s Progress’, with much more practical advice and lists – for example, what was needed in a baby’s basket. In many respects, though, traditional expectations towards women becoming mothers still prevailed in the 1930s, and rigid ideas about how a mother should and should not bring up her children persisted.

Throughout this book, Cow and Gate take opportunities to advertise their milk for babies, using diagrams to demonstrate the high levels of bacteria in raw cow’s milk compared to their own formula.

As well as having a huge impact on female nursing, the First and Second World Wars threw issues around disability, first aid and nutrition into the national spotlight.

More recently, investigations into the mental toll of war have received a large amount of attention. This is in part due to enhanced understandings of mental health today, and the modern conflicts which remind us daily of the trauma that war can cause for those involved. Attitudes towards victims of war were not always so progressive, and the Museum collection demonstrates a sometimes jarring clash between sympathy for the wounded and contempt for the suffering of those with resulting long-term disabilities.

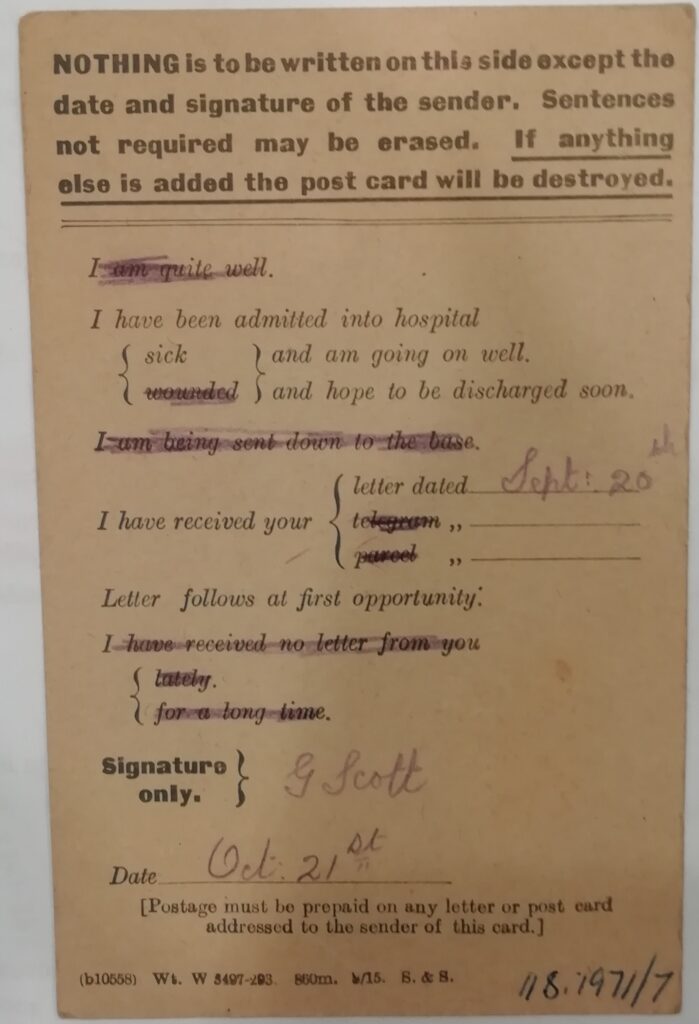

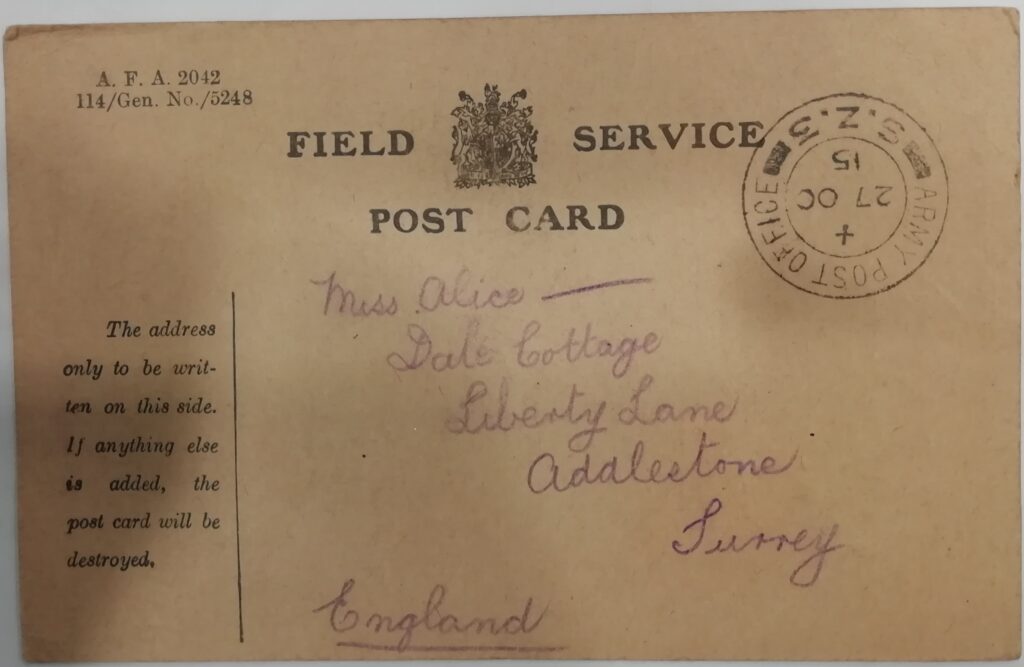

Field service postcard addressed to a Miss Alice, of Liberty Lane, Addlestone, October 1915.

This field service postcard was sent to inform the recipient – likely to have been a relative of the service person in question – that their family member had been admitted to hospital sick while serving in the First World War.

The top of the page warns that ‘NOTHING is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender… If anything else is added the post card will be destroyed.’ This was to control and censor the information which was reaching civilians about the way the war was going or the conditions the troops were facing.

The postcard contains a list of options for the sender to strike-through as appropriate, including ‘I have been admitted into hospital sick / wounded’. The mental anguish this could cause families back at home was pronounced, as the sender was not allowed to write any other details of their injuries or their severity.

Field service postcard addressed to a Miss Alice, of Liberty Lane, Addlestone, October 1915.

Field service postcard addressed to a Miss Alice, of Liberty Lane, Addlestone, October 1915.

Field service postcard addressed to a Miss Alice, of Liberty Lane, Addlestone, October 1915.

Field service postcard addressed to a Miss Alice, of Liberty Lane, Addlestone, October 1915.

Images 1 – 2: Metal ‘Squires Sterilised Surgical Dressings’ box, c.1914-18.

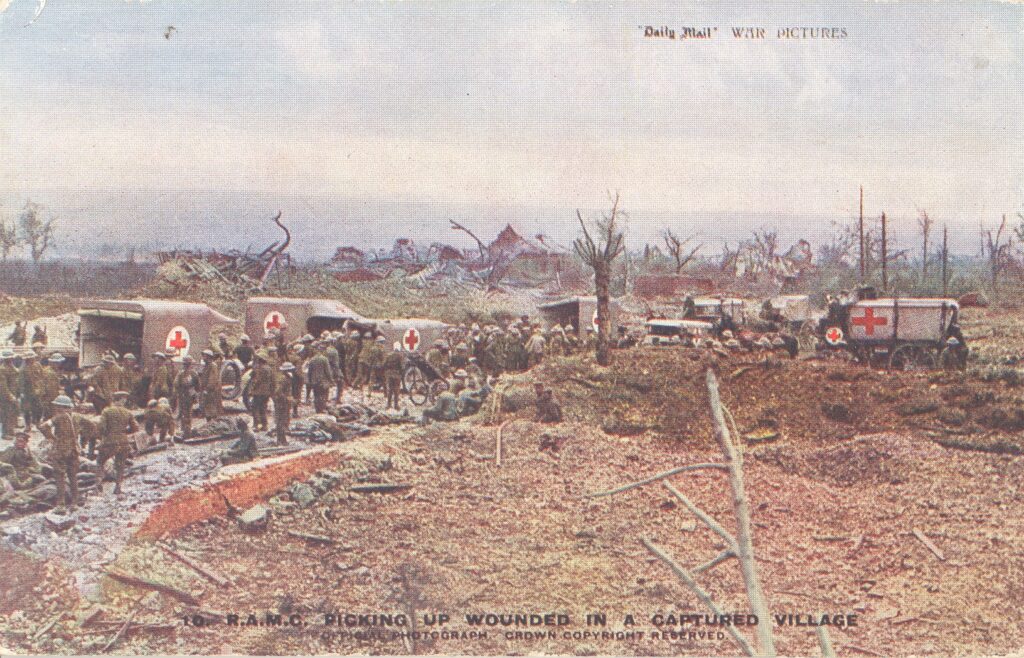

Image 3: Colour postcard from the First World War, entitled ‘RAMC Picking up wounded in a captured village.’ It was part of an 18 card series in the Daily Mail Official War Pictures Series 2, depicting life at the Front in the War.

This medical box, used during the First World War, contains a roll of dressing and a compliment slip from the producers, as well as another small steel container holding a glass syringe and two needles.

The number of new weapons being used in the conflict increased the range of injuries which could be inflicted on soldiers, and as a result the war saw a number of medical advancements. These included the first use of X-ray technology, advancement in antiseptic treatment and the first successful blood transfusions. Emergency treatments on the battlefield were usually carried out by the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), and portable kits like this were very common. Needles and syringes could have been used to administer anaesthetics, saline, or for blood transfusions while at the front.

Metal ‘Squires Sterilised Surgical Dressings’ box, c.1914-18.

Metal ‘Squires Sterilised Surgical Dressings’ box, c.1914-18.

Inside the metal ‘Squires Sterilised Surgical Dressings’ box, c.1914-18.

Inside the metal ‘Squires Sterilised Surgical Dressings’ box, c.1914-18.

'R.A.M.C picking up wounded in a captured village', Daily Mail Official War Pictures series, 1914-18.

'R.A.M.C picking up wounded in a captured village', Daily Mail Official War Pictures series, 1914-18.

Image 1: Postcard of the New Zealand hospital at Mount Felix, showing soldier patients and nurses standing on the steps of the house. In the front is an older patient in a long lie-back wicker push-chair with large wheels, and many of the surrounding soldiers use crutches or wear bandages, c.1915-18.

Image 2: Postcard showing wounded New Zealand troops in a production of ‘The Vicar’s Daughter’, perfomed in the theatre at Mount Felix Hospital, December 1915.

Image 3: Postcard of a Christmas party in a Mount Felix Hospital ward, December 1917. Some men lie in the row of beds down each wall, others sit at tables down the central aisle, with nurses standing behind them. Many are wearing paper hats and the ceilings and tables are decorated with holly.

In 1915, that Mount Felix mansion, next to Walton Bridge, was offered up for use as a 150 bed hospital for ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) First World War servicemen, a huge number of whom had been injured in the Gallipoli Campaign. In January 1916, five large timber ward huts were built to the south of Bridge Street between Oatlands Drive and the River Thames. Named Anzac Mount, this area was linked to the main buildings by a covered walkway and a footbridge. The hospital was a hugely significant feature of Walton throughout the war, and the soldiers treated there integrated well into the local community.

The photos here demonstrate the various methods for dealing with physical injuries a century ago, including wooden crutches and lie-back wicker push-chairs, but also the ways in which the strain on soldiers’ mental health could be lessened, through light relief such as amateur dramatics and Christmas parties.

Learn more about Mount Felix War Hospital The New Zealand hospital at Mount Felix, c.1915-18.

The New Zealand hospital at Mount Felix, c.1915-18.

Wounded New Zealand troops in a production of ‘The Vicar’s Daughter’, perfomed in the theatre at Mount Felix Hospital, December 1915.

Wounded New Zealand troops in a production of ‘The Vicar’s Daughter’, perfomed in the theatre at Mount Felix Hospital, December 1915.

A Christmas party in a Mount Felix Hospital ward, December 1917.

A Christmas party in a Mount Felix Hospital ward, December 1917.

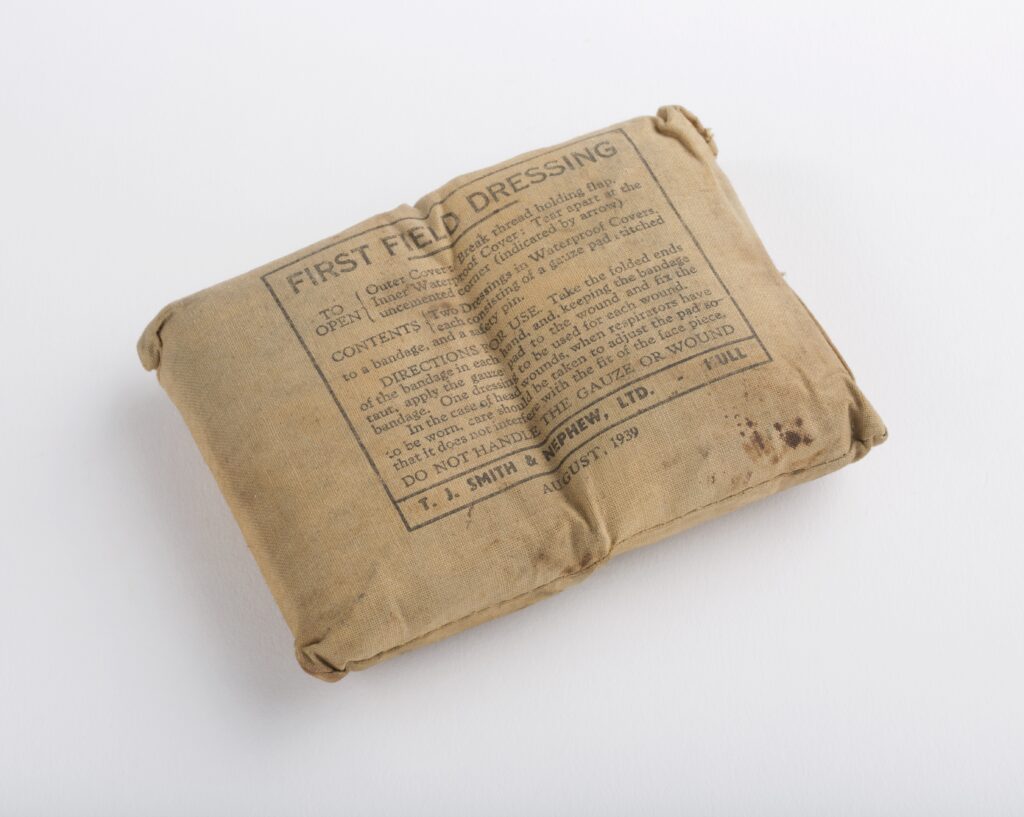

Image 1: T.J. Smith & Nephew Ltd. pack of 2 gauze pads in waterproof covers, August 1939.

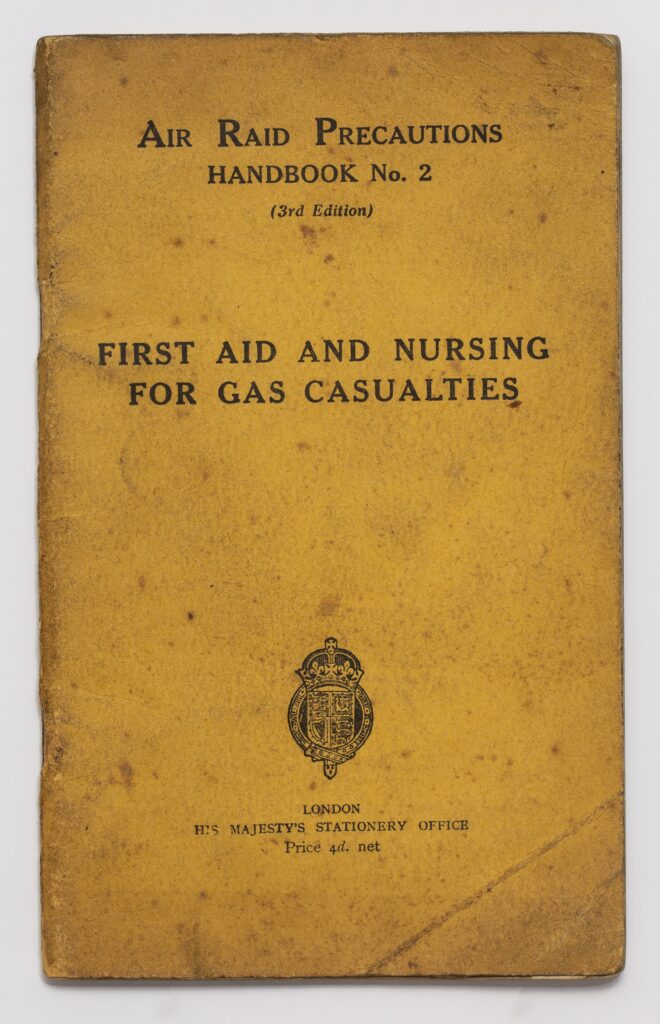

Image 2: Air Raid Precautions Handbook covering ‘First Aid & Nursing for Gas Casualties’, c.1938-45.

Image 3: Anti-gas No.5 ointment in a blue tin with instructions on the reverse, c.1939-45.

Image 4: Anti-gas drill by a gun site in Walton, with men from The Sparrows Force fitting gas masks and capes, c.1939.

During the Second World War, the hugely increased threat to civilian safety through enemy bombing raids meant it was essential that as many civilians as possible had knowledge of first aid and the necessary equipment to deal with injuries. The Air Raid Precautions Handbook here was the official document used by the donor’s father in the Walton Home Guard during the Second World War. It focuses heavily on nursing for gas casualties, and likewise the anti-gas ointment would have been an essential piece of kit Air Raid Precaution Wardens would have carried.

The prospect of a German chemical weapon attack hung over the British population as a constant threat throughout the conflict, and gas drills were carried out across the entire country – image 4 shows a drill being carried out by the Sparrows Force, a territorial unit in Walton formed in 1938 and attached to the Royal Artillery in 1939.

In addition to first aid guides and gas ointment, gas masks were carried by every civilian and gas rattles would have been used to raise the alarm. The tin of anti-gas ointment could both decontaminate skin affected by poison mustard gas and prevent or lessen the severity of burns if applied before exposure.

Discover more about Elmbridge in the Second World War 2 gauze pads in waterproof covers, August 1939.

2 gauze pads in waterproof covers, August 1939.

‘First Aid & Nursing for Gas Casualties’, c.1938-45.

‘First Aid & Nursing for Gas Casualties’, c.1938-45.

Anti-gas No.5 ointment, c.1939-45.

Anti-gas No.5 ointment, c.1939-45.

Anti-gas drill by a gun site in Walton, c.1939.

Anti-gas drill by a gun site in Walton, c.1939.

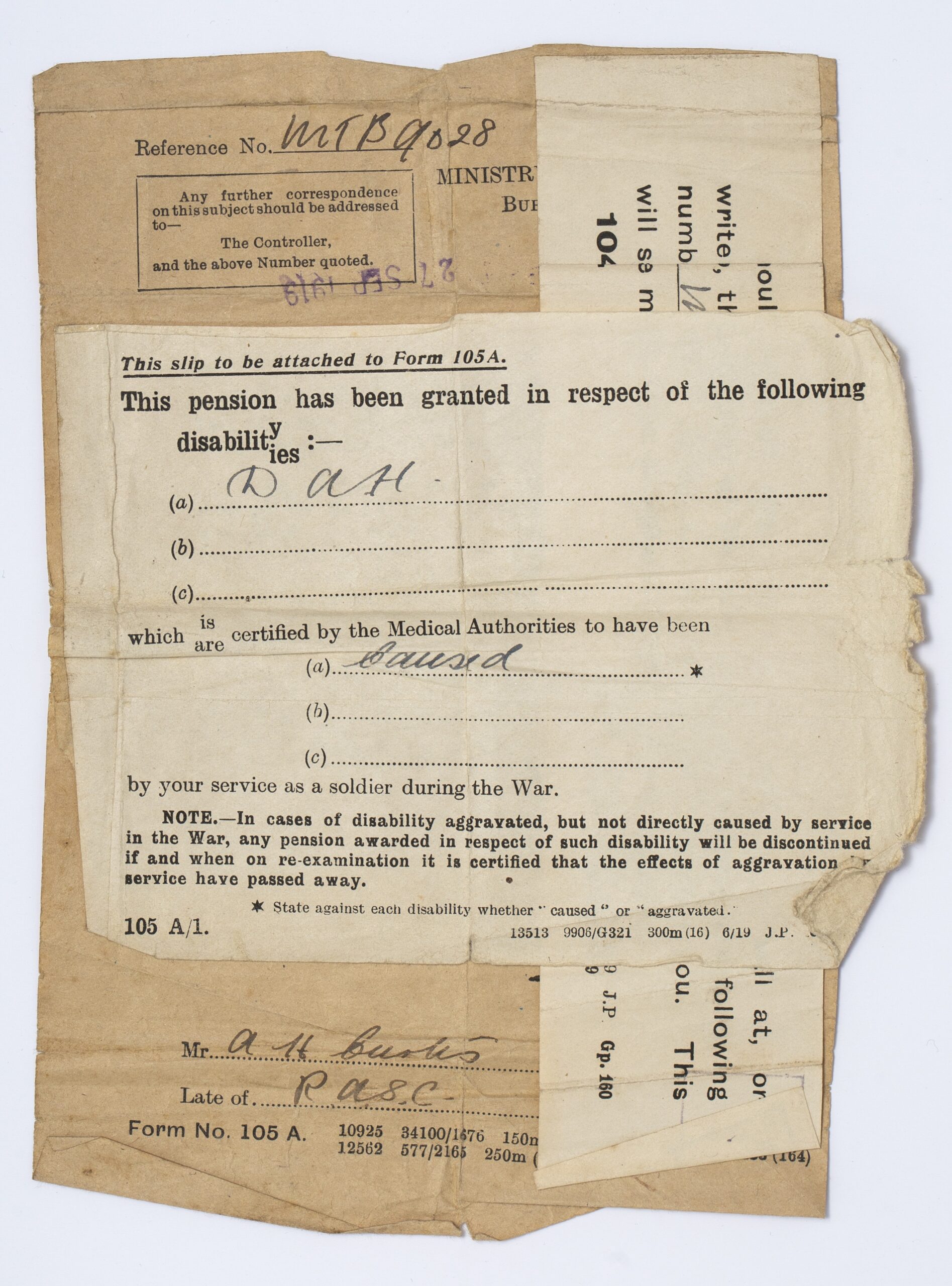

A form for Private A. H. Curtis relating to the payment of his war disability pension by the Ministry of Pensions, September 1919.

In the years directly following the 1918 Armistice, there was general sympathy for First World War veterans who had suffered from disabilities and mental health issues due to their time in service. As the years progressed, however, this sympathy gradually ebbed away. Those who were still suffering from trauma into the 1920s were often viewed as ‘malingerers’ and sometimes criticised for being unable to work. These attitudes were both reflected in and encouraged by the government’s treatment of disabled or sick veterans.

This pension form states that A.H. Curtis’ disability was D.A.H, referring to ‘Disorderly Action of the Heart’. It was sometimes known as ‘soldier’s heart’ and related to stress or fatigue. In this case, the D.A.H that Curtis was suffering from is stated to have been caused by his service as a soldier, and he could therefore receive a set disability pension. But others may have faced complications, as the form states clearly that “in cases of disability aggravated, but not directly caused by services in the War, any pensions awarded in respect of such disability will be discontinued if and when on re-examination it is certified that the effects of aggravation from service have passed away.” This resulted in a grey area where, in some cases, the government could avoid paying disability pensions after a time if it could be proved the veteran had suffered from health issues before serving.

Other leaflets from this time indicate the harsh attitude towards compensating those whose lives had been irreversibly changed by compulsory service. One form sets out the varying amounts of money a war amputee could claim, based on which limb had been amputated and how much of the limb in question was missing. These hugely insensitive methods for calculating veterans’ disability pensions were standard after the First World War, a time when understanding of the lives of those with disabilities and mental health conditions was only just developing.

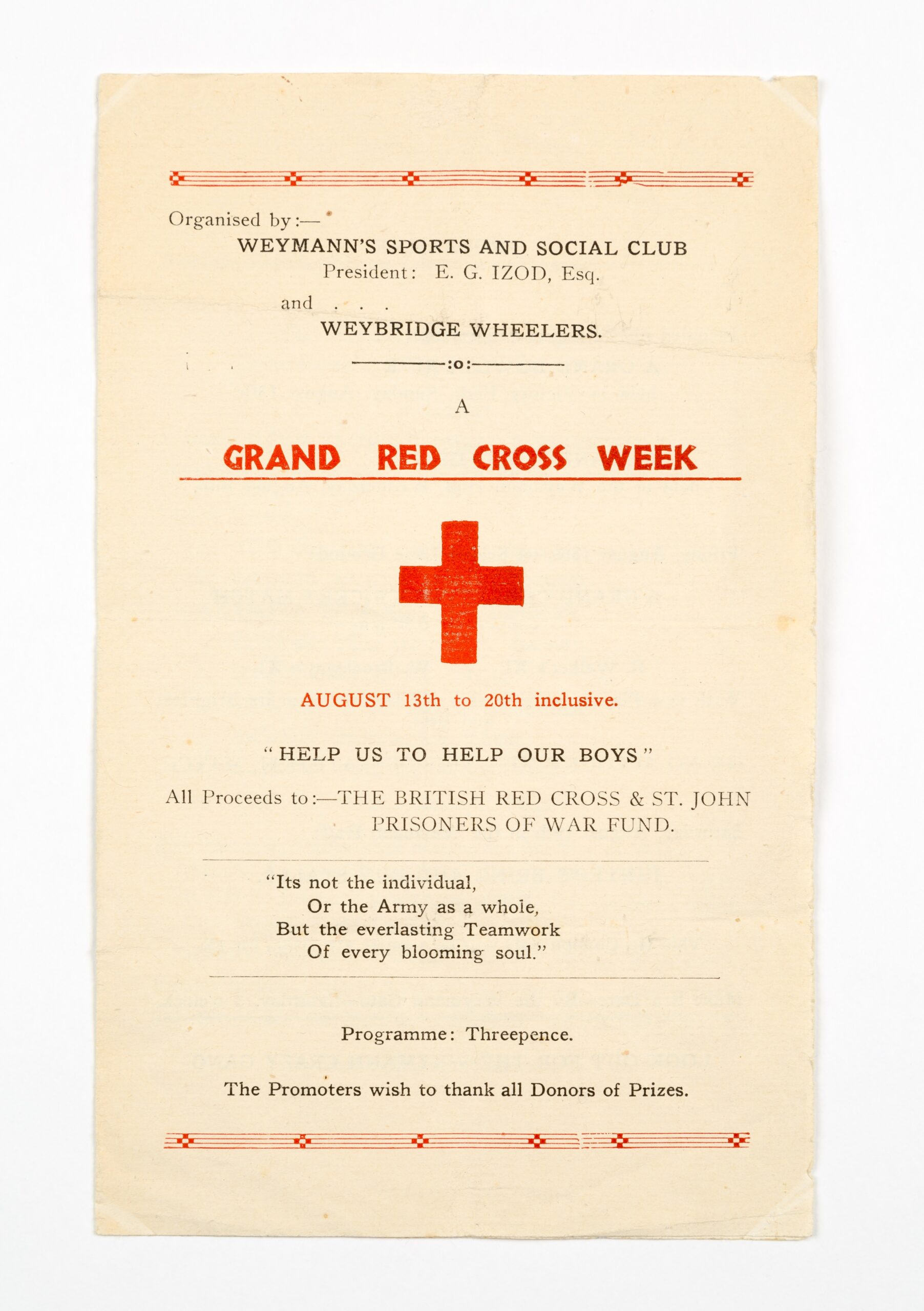

Programme for ‘A Grand Fete’ during Red Cross Week, August 1945.

This programme shows a very different attitude towards wounded soldiers and veterans than the pension form above. The Red Cross ‘Grand Fete’ took place over the 13th-20th August, the very week that Victory over Japan was declared on 15th August and 3 months after Victory in Europe had been celebrated on 8th May.

Grand Red Cross week was designed to ‘help us help our boys’, raising money for the Red Cross and the St John Prisoners of War Fund to help demobbed men and returned prisoners in need of medical care. It included a tug of war competition, tilting the bucket, obstacle races and a charity cricket match, as well as ‘bring and buy’ stalls. The back of the leaflet states that “there is always some lame dog that needs helping over the stile and there is always some one on hand to do it… Starting in 1939 by sending a few smokes, razor blades, writing paper, or whatever “the boys” asked for this fund now sends to “our boys” the total of £1,200 per year. This sum is raised purely voluntarily and stands as an achievement to be proud of. The aim now is to have £1,000 in the bank by the time “our boys” return, which will be used in gratuities, which will be the Weymann expression of “Thanks Pal, for the job you have done”.”

The cheery attitude of thanks and the sums of money raised illustrates a warm public feeling towards those who had served in the war, but it perhaps fails to recognise the very real mental and physical injuries so many service personnel were suffering, and the scale of this ongoing problem even after the war had ended.

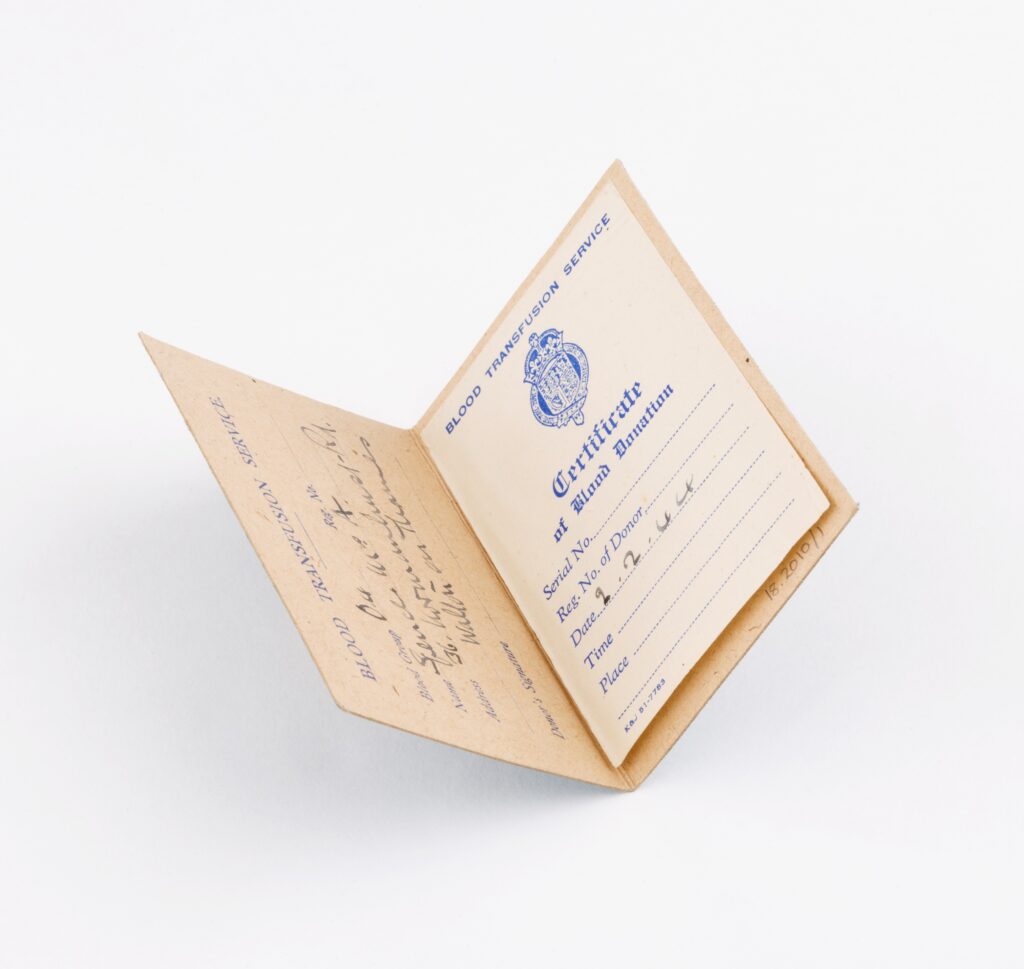

‘Blood Transfusion Service Donor’s Certificate’ for Mrs A Spencer of Normanhurst Road, Walton, who gave blood in February 1944.

The process of blood transfusion had developed significantly during the First World War, but techniques for storing donated blood other than for preventing coagulation were undeveloped, so the blood used for transfusions had to be relatively new. However, from 1937 the first blood banks were set up, just before the need for emergency blood to help both soldier and civilian casualties again exploded during the Second World War. By 1944, the Emergency Blood Transfusion Service had set up 900 centres across the country for blood donations and civilians were being encouraged to donate blood through posters and propaganda.

'Blood Transfusion Service Donor's Certificate', February 1944.

'Blood Transfusion Service Donor's Certificate', February 1944.

'Blood Transfusion Service Donor's Certificate', February 1944.

'Blood Transfusion Service Donor's Certificate', February 1944.

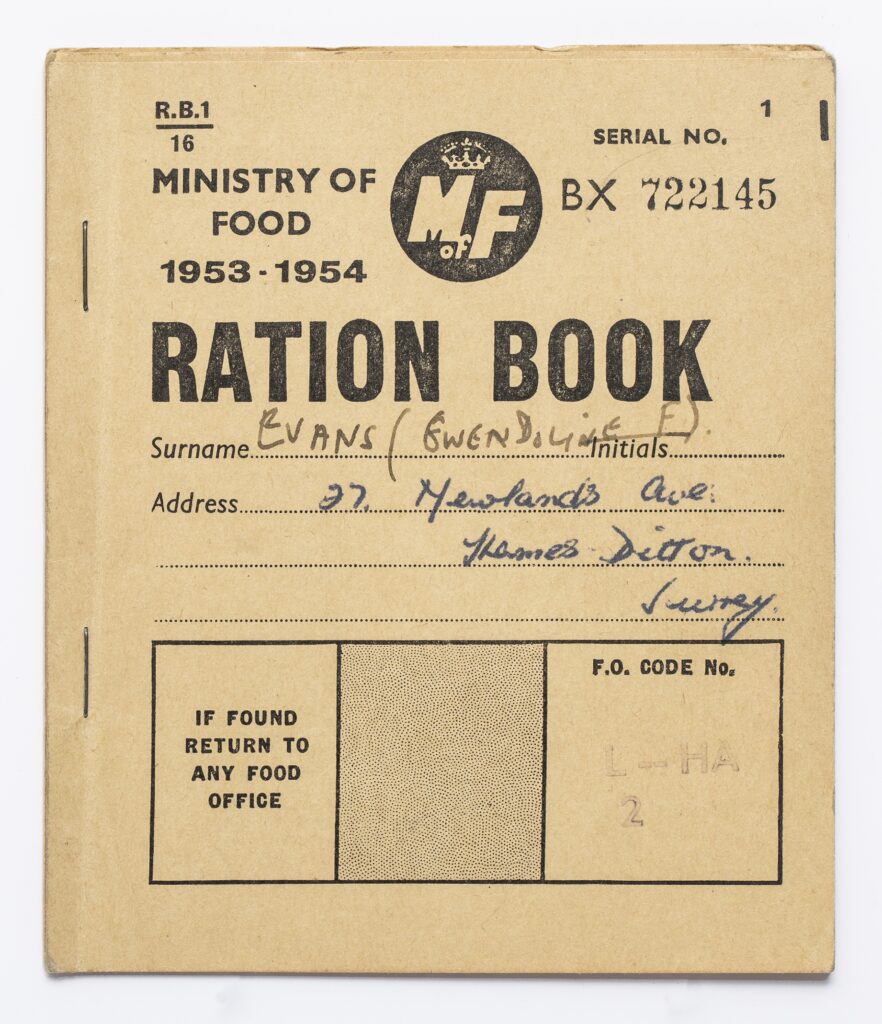

Image 1: Ration book for food belonging to Gwendoline F. Evans from Newlands Avenue, Thames Ditton, c.1939-45.

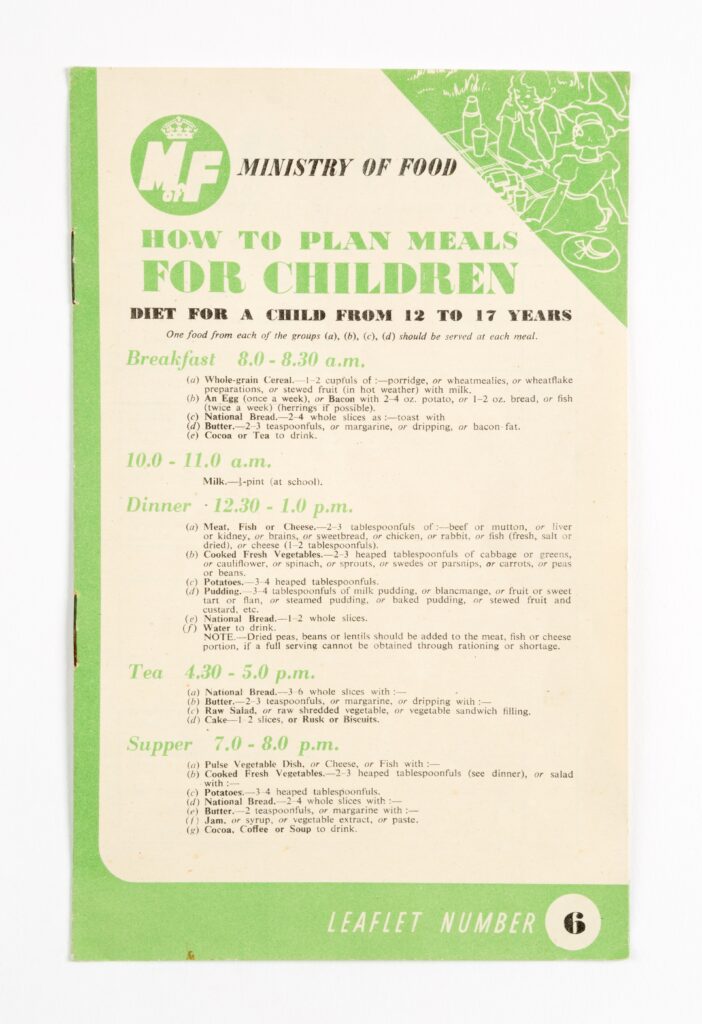

Image 2: Ministry of Food recipe leaflet on ‘How to plan meals for children’, c.1939-45.

Images 3 – 5: The Land Army allotments at Secrets Farm, Hersham, 1944-5.

Food rationing in the UK began in January 1940, and by mid-1942 most foodstuffs were rationed apart from bread and vegetables, which could often be made or grown at home. Before 1939, the UK imported more than half of most of its food supplies, so when the Germans started to attack British imports, rationing was a necessity to ensure the limited supplies could feed the population of 50 million. Ration books like this were distributed to every person, and Elmbridge Museum holds many examples of ration books for different items, including fresh food, tinned food, and fuel.

Eating healthy and nutritious meals during this time of national shortage was challenging for many families, and as a result the government produced propaganda campaigns like ‘Dig for Britain’ to encourage people to grow their own food where they could. Additionally, leaflets such as this one in image 2, issued by the Food Advice Division of the Ministry of Food, helped parents to make their rations go as far as possible and maintain a balanced diet for their children.

Women in the Land Army were recruited to help manage food shortages by growing and harvesting vegetables across local areas. The ones in images 3 – 4 were working at Secrets Farm (now known as Bell Farm) in Hersham. The farm contained of fields for growing vegetables like cabbages, as well as 6 large greenhouses. The women used a narrow gauge railway line bordering the perimeter of the farm to more easily pack and transport harvested produce.

Ration book for food belonging to Gwendoline F. Evans, Thames Ditton, c.1939-45.

Ration book for food belonging to Gwendoline F. Evans, Thames Ditton, c.1939-45.

Ministry of Food recipe leaflet, c.1939-45.

Ministry of Food recipe leaflet, c.1939-45.

Fields of cabbages with 6 large greenhouses at Secrets Farm, Hersham, c.1944-45.

Fields of cabbages with 6 large greenhouses at Secrets Farm, Hersham, c.1944-45.

Photograph of 5 women planting seeds at Secrets Farm (Bell Farm), Hersham, c.1944-45.

Photograph of 5 women planting seeds at Secrets Farm (Bell Farm), Hersham, c.1944-45.

All the Land Army working at Secrets Farm, Hersham, c.1944-45. There are 25 girls and women, 1 boy, and a Jack Russell terrier.

All the Land Army working at Secrets Farm, Hersham, c.1944-45. There are 25 girls and women, 1 boy, and a Jack Russell terrier.

Wounded and disabled veterans were a common sight across most local areas in the aftermath of both the First and Second World Wars

In 2019, Elmbridge Museum’s ‘Memories of War’ oral history project revealed many fascinating stories of locals during the Second World War. In this interview clip, Alan from Tolworth talks about how one local soldier’s life-changing injuries sustained in the conflict affected his life in the aftermath of war.

Listen to more interviews from the projectMuch like attitudes towards disabled veterans after the wars, public understanding of mental health conditions has tended to be unsympathetic right up until the modern day. To some extent, a stigma still exists around mental illness, but in the early 20th century and prior to this, mental illness was usually equated to ‘madness’ or ‘insanity’ and sufferers might have been sent to a mental asylum, known for their draconian methods and long admittance times. Health problems were often particularly amplified amongst the poorest in society, who may not have had the means to be treated properly for illness. Those amongst the poor who couldn’t work or support themselves, for whatever reason, often ended up in one of the thousands of prison-like workhouses across the country, a system which was only eradicated as late as 1948.

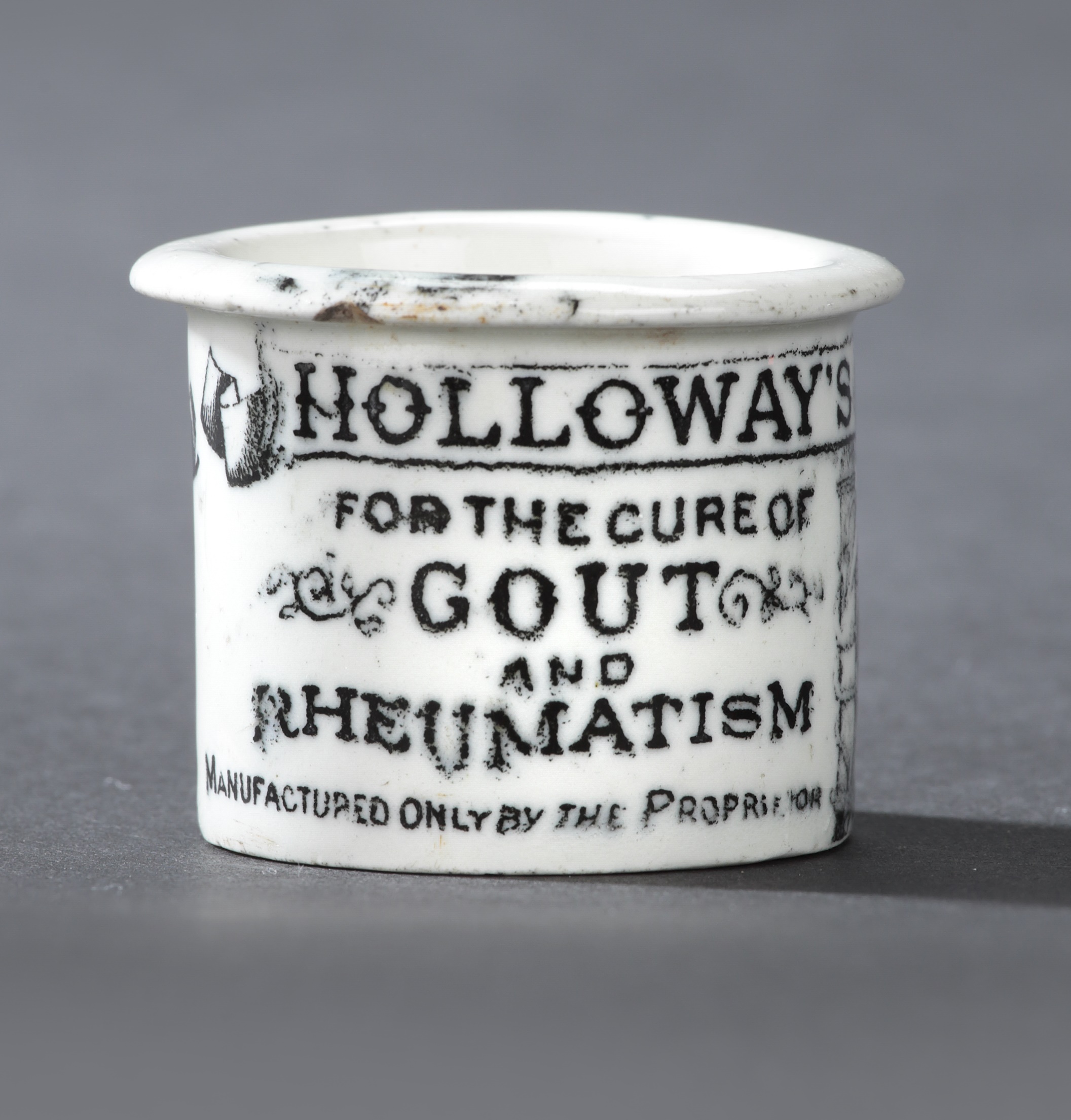

A ‘Holloways’ ointment jar for curing gout and rheumatism, c.1880s.

A ‘Holloways’ ointment jar for curing gout and rheumatism, c.1880s.

Thomas Holloway was a Victorian businessman and philanthropist. He is perhaps best known for founding Royal Holloway college for women in the 1880s – now Royal Holloway University of London. However, Holloway had initially made his fortune through the sale of pharmaceutical ointments and pills which were hugely popular across Victorian society and even used by Queen Victoria herself. This ointment jar claims to cure gout and rheumatism, however, today Holloway’s remedies are widely recognised to have been little more than herbal remedies which would have mainly relied on the placebo effect.

Holloway invested a large proportion of the fortune he made through his medicines into opening his own private sanatorium in Virginia Water in 1885, housing 240 patients with a range of mental health conditions. This would have been exclusively for patients who could afford the admittance fees, and was sold as adopting a progressive approach towards the treatment of mentally ill patients. Despite this, letters and paperwork that survive in Surrey History Centre relating to patients of the Sanatorium sometimes reveal their anguish at being incarcerated within the institution.

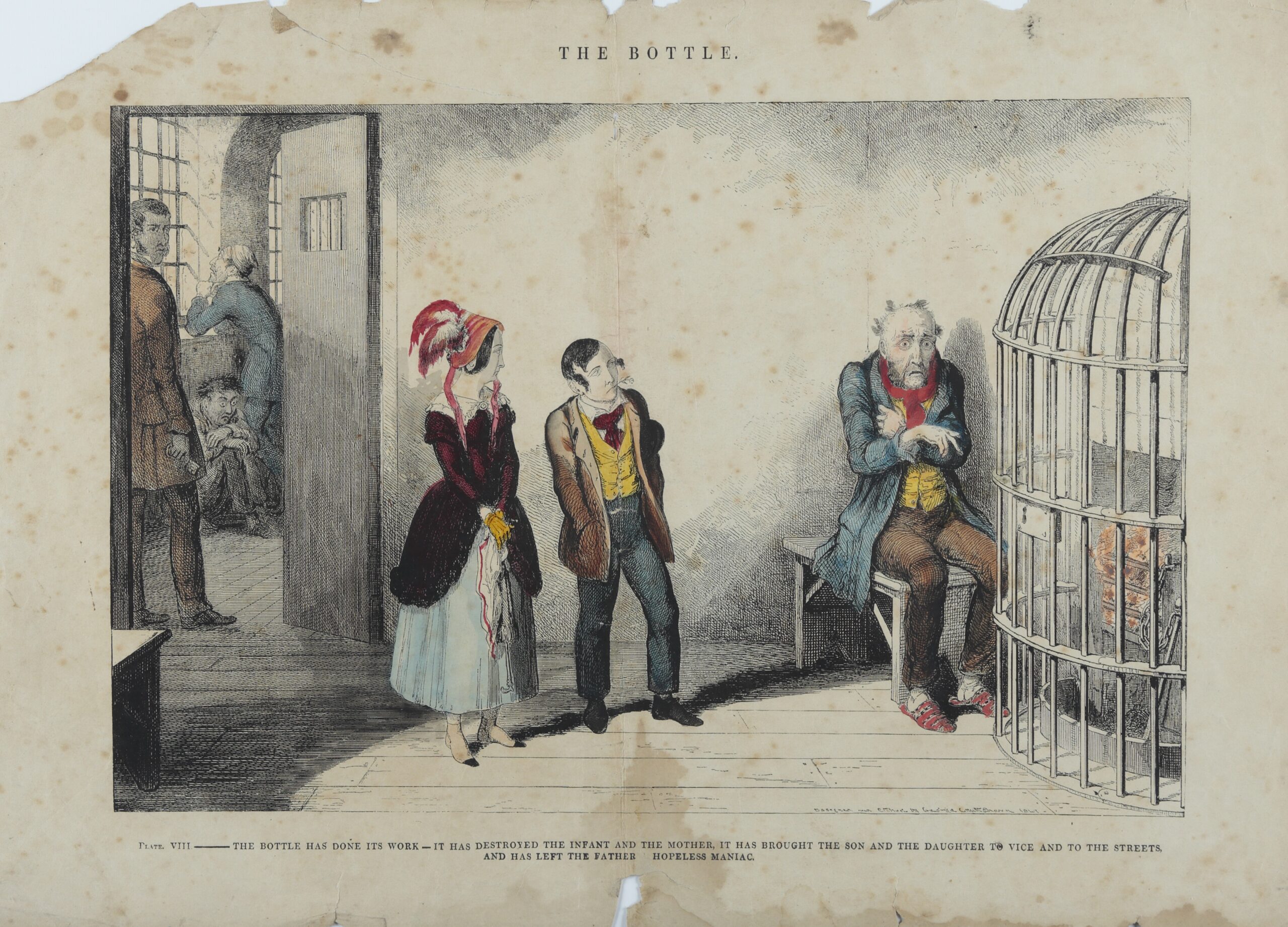

Plate VIII of 'The Bottle' series by the famous glyphographic artist, George Cruikshank, 1847.

Plate VIII of 'The Bottle' series by the famous glyphographic artist, George Cruikshank, 1847.

This coloured print was part of a series of prints collectively titled ‘The Bottle’. The earlier prints in the series aim to demonstrate the gradual descent of a Victorian family into vice due to the influence of alcohol. This panel – one of the last – shows the supposed result of drinking according to the artist. It is captioned “The bottle has done its work – It has destroyed the infant and the mother, it has brought the son and the daughter to vice and to the streets, and has left the father a hopeless maniac.” George Cruikshank was heavily involved In the Victorian Temperance Movement which began in the 1830s. ‘The Bottle’ was therefore designed to discourage people from drinking, believed to cause a range of societal ills including poverty, immorality, violence, illness, and insanity.

In the mid-1800s, Cobham itself was labelled as “drenched in drink and wickedness” by a visiting minister, thanks in part to its 15 pubs [David Taylor, ‘Cobham Brewery: A Short History’, Esher District Local History Society, 1972] . This print helps to demonstrate the widespread view that mental illness and addiction were self-inflicted, a reflection of someone’s immoral or foolish life choices.

Most parishes had at least one workhouse by the 1830s. From 1773, a property in Walton at Hole Corner was leased for use as a workhouse. It was relatively small, housing 50 inmates, and likewise the workhouse at Weybridge in the late 1700s housed about 20 inmates. From 1834, with the Poor Law Amendment Act, these both operated within Chertsey Poor Law Union, covering a total population of over 13,000 people. Unfortunately, because both workhouses were so small not much information survives about the people admitted to them, but we do know that the poor needing medical care would apply to the Overseers of the Poor for relief and thereafter possibly be admitted to a local workhouse.

Edward Hassell (1811-52) was the son of John Hassell (1767-1825). Together, they painted over 2,000 watercolours of Surrey during the period 1820 to 1832. Both artists exhibited at the Royal Academy and earned their living as drawing masters.

Conditions in these workhouse institutions, particularly in the larger ones, could be squalid – smallpox was rife, and crowded, unsanitary conditions allowed disease to spread easily. Working conditions could also be dangerous and injury while working with machinery was a huge risk. In 1841, Surrey’s first county asylum was opened at Springfield in Wandsworth, and this took in the sickest of workhouse inmates in Surrey.

E.M. Synge came to Eastlands as Peter Locke-King's land agent in 1885 and died in 1913.

The ‘Poor Man’s Friend’ was a popular 19th – 20th century remedy claiming to help longstanding skin conditions and ‘wounds of every description’ like gout, cuts, scalds, chilblains, pimples, ulcers and gangrene. It was invented by Giles Laurence Roberts, a Dorset pharmacist and doctor. The remedy took off after becoming popular in Dorset amongst those of restricted means, looking for relatively cheap remedies to ailments. Upon his death, Roberts left the recipes for the Poor Man’s Friend to Thomas Beach and John Barnicott, who sold the remedy until 1946.

In the early 2000s, it was discovered that the ingredients consisted of mainly lard and beeswax, combined with a toxic combination of harmful chemicals such as mercurous chloride and sugar of lead.

It can be difficult to find evidence of how people in Elmbridge’s past looked after their health day-to-day. Issues surrounding mental health, in particular, often came with a heavy stigma, and it was not uncommon for people to try to cover up mental illness as much as possible.

The Museum collection holds a number of diaries, letters, log books and personal accounts written by historic residents which reveal how they experienced daily life at a given time. This softer, more personal evidence can be just as useful as more formal documentation like hospital records in finding out how people have stayed healthy throughout history. Indeed, most people in the past, as today, would only visit the doctor infrequently, at times when they were particularly suffering, if at all. Personal accounts can therefore help us to fill in the gaps between these times of interaction with formal healthcare.

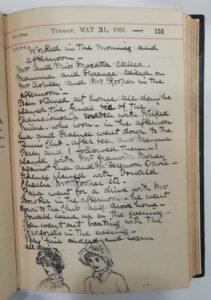

This diary (left and opposite) was kept by May Hawes in 1881, whilst living at Cherrahurst, Pine Grove, in Weybridge. The diary recounts her daily activities and those of her family during 1881.

The pages of the diary are illustrated by sketches of people and places in Weybridge and on each page May talks about her daily activities over 140 years ago. Many of these activities were focussed around maintaining good health as well as for recreation. Often, May and her friends and family would take walks to Oatlands Park or in Church Fields, play tennis, go out sketching or row on the River Thames:

“Tuesday, May 31, 1881

Worked in the morning and afternoon…

Mamma and Florence called on Mr Ashley and Mr Rooper in the afternoon.

Ben stayed at home all day, he played the final tie of the Championship match with Wilfred who won. In the afternoon Eva and Florence went down to the Tennis Club, after tea, and Mamma, Percy and I followed them. I played with Mr Granville against Eva and Mr Ferguson…

Papa went for a drive with Mr Bowker in the afternoon – he went down the Club and drove home. Oswald came up in the evening.

Ben went out boating with the Radfords in the evening.

Very fine indeed and warm all day.”

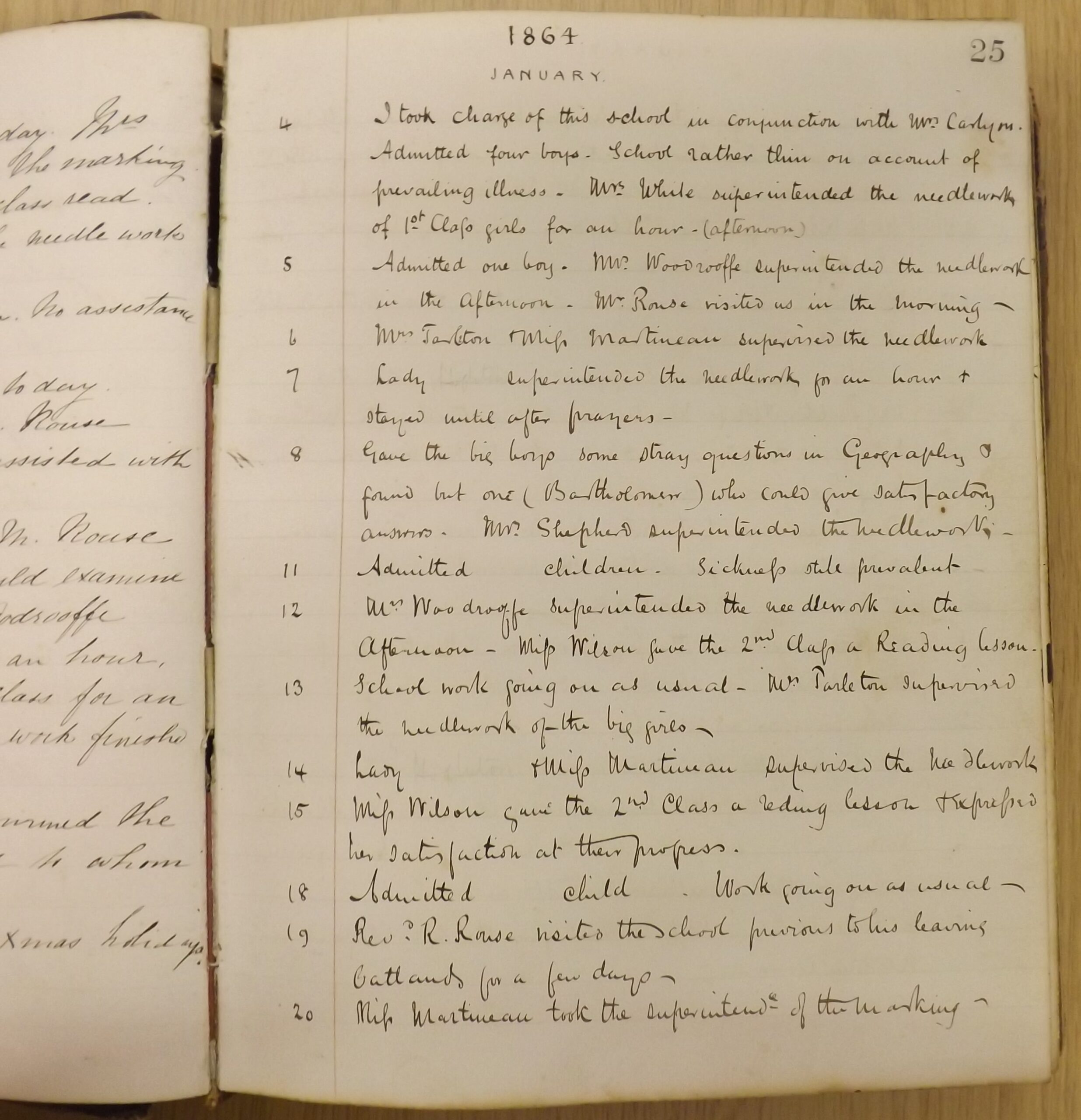

Cloth and leather bound handwritten Log Book from Oatlands School, December 1862 - January 1883.

Cloth and leather bound handwritten Log Book from Oatlands School, December 1862 - January 1883.

This cloth and leather bound log book contains a handwritten account of each day at Oatlands School from December 1862 to January 1883. It provides a fascinating insight not only into school life, but into how seasonal illness affected both students and staff in this time.

There are various entries from the log book which mention sickness directly, in particular across the year 1864-5. Throughout this year, one of the teachers, Mrs Carlyon, was affected by regular bouts of illness which clearly impacted the students’ education.

‘1864

4th January: I took charge of this school in conjunction with Mrs Carlyon. Admitted four boys. School rather thin on account of prevailing illness. Mrs. White superintended the needlework of 1st Class girls for an hour (afternoon).

4th May: Mrs Carlyon unwell and unable to attend school in the afternoon.

23rd September: Mrs Carlyon very poorly – but managed to attend school.

26th September: Mrs Carlyon not in school, having been confined on Saturday last.

25th November: Mrs Carlyon taken ill again.

28th November: Mrs Carlyon not in school, being very ill indeed. Mrs White was most kind to her.

2nd December: Mrs Carlyon still very ill indeed.

6th December: Work going on fairly – not altogether satisfactorily inasmuch as there is no one to take Mrs Carlyon’s place.

14th December: Very much dissatisfied with work owing to Mrs Carlyon’s absence. Examined the 1st Class and 2nd.

1865

9th January: Opened with few children – Mrs Carlyon again in school after her illness.

Local health centres and surgeries are the main ways in which most people interact with healthcare day-to-day. Many of these institutions date back to the early 20th century, and have evolved over time. Elmbridge Museum holds many items from the history of the Walton, Hersham and Oatlands Cottage Hospital, revealing the importance of this particular local health centre to the community over the last century.

This postcard shows the Walton, Hersham and Oatlands Cottage Hospital on the corner of Sydney Road and Rodney Road, c. early 20th century.

This is the fourth Report of the Walton-on-Thames, Hersham & Oatlands Cottage Hospital for 1908. It contains a report, details of patients' illnesses, accounts, subscription and rules. The cottage hospital had opened in June 1905, and closed in the early 1990s. Mrs Morgan had been the medical secretary there in the 1970s, and collected these records prior to its closure, donating them to the Museum.

The report states the Committee's thanks to the Medical Officers for their services, especially mentioning a Miss Brown, who was a Matron there.

There were 172 patients admitted to the hospital in 1908, fifty more than the year before. 79 surgical operations were performed, and the average length of stay for these patients was 16 and a half days.

The report goes into detail about each of these patients' ailments, and whether they were cured, improved, relieved, transferred to another hospital, or died.

Some of these illnesses include terms we would not recognise in modern health care - such as the male who was admitted with a 'poisoned hand' and was cured, or the female cured of a 'hysteroid attack'. Many diseases listed are ones which could be more easily prevented today, with the following page sadly noting a female who died of 'infantile diarrhoea'.

This booklet contains an order of ceremony for the opening of Walton, Hersham and Oatlands Cottage Hospital in 1904. The Duchess of Albany laid the foundation stone on 28th May 1904. We know that the local cottage hospital was much supported and appreciated in the local area thanks to the 1908 report.

As well as mentioning the large sums of money donated to the hospital and collected from subscribers and patients who could afford to pay, the report also states that "through the generosity of a few, a small Organ has been provided for the Hospital, and has been much appreciated by the Nurses and Patients." It also includes a note from the Matron asking that ladies making gifts of clothing for the use of patients "communicate with her as to suitable patterns and materials." The report concludes by stating "the generally acknowledged usefulness of the Institution to the poorer residents of the district in times of sorrow and suffering."

Various methods were used to raise money for the local cottage hospitals.

This photograph is of the crafts and fancy goods stall at the Walton, Hersham and Oatlands Cottage Hospital Garden Fete, c.1932-34.

This photograph, another from the Walton, Hersham and Oatlands Cottage Hospital Garden Fete, shows of a group of women in pantaloons, tunics and headbands at a stall, c.1932-34.

The Second World War affected local health and nursing in many ways. Learn more about the war in Elmbridge in our 'Elmbridge at War' online exhibition.

Go to the online exhibition