Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

Explore the latest news and find out what's on this month

Explore our learning offer for schools, families and community groups

Uncover the rich history of Elmbridge with our latest online exhibitions

Want to discover more about your local area?

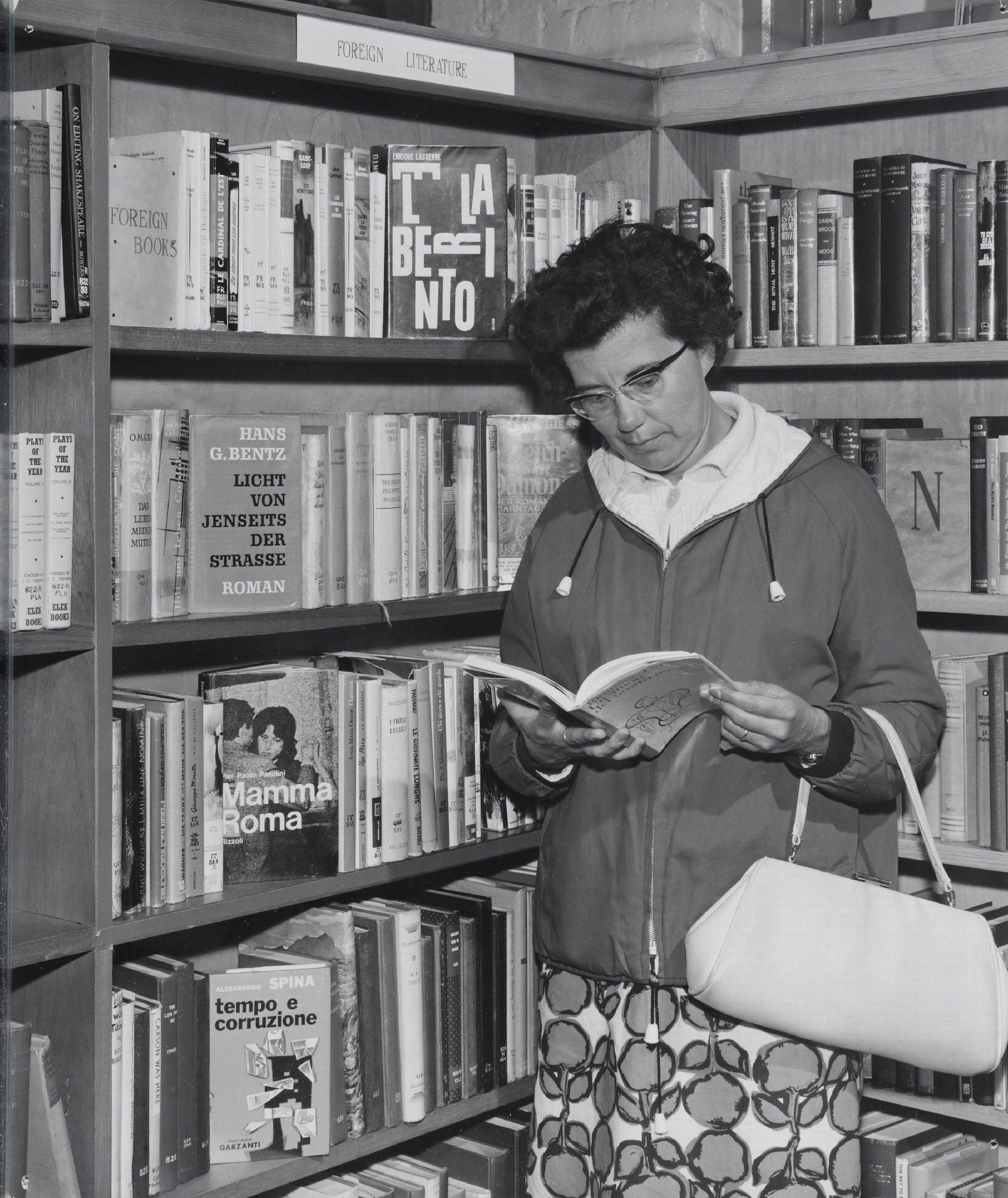

Interior of Walton Library, showing a member of the public looking at a book in a foreign language in front of a bookcase labelled "Foreign Literature", 1965.

Interior of Walton Library, showing a member of the public looking at a book in a foreign language in front of a bookcase labelled "Foreign Literature", 1965.

Literature exhibits itself in almost every aspect of our modern lives: from reading a romantic novel or writing a friend’s birthday card, to teaching our children about the world or keeping up to date on the news of the day.

There is no doubt that literary culture permeated the lives of our forebears as much as it influences us. Because of this, surviving historic literature provides a vital link to Elmbridge’s past.

In this exhibition, originally launched alongside the 201-22 R.C. Sherriff Trust Elmbridge Literary Competition, we explore what the historic, practical and personal literature in Elmbridge Museum’s collection reveals about the time in which it was written, as well as delving into the theme for the 2021-22 competition: ‘Enigma’. Why not submit your own literary piece to the comment section at the bottom of this page?

Visit the Elmbridge Literary Competition page

Black and white photograph of a painting of Sarah Austin.

Born in Norwich as one of seven in 1793, Sarah went on to excel in French, German Italian and Latin. She subsequently produced many translations from the 1820s – 1830s, such as the ‘Characteristics of Goethe’ and Ranke’s ‘History of the Popes’.

Sarah was also an author in her own right. Around nine years before moving to Elmbridge, she penned her ‘Considerations on National Education’ (1839). In this work, she advocated education for all. This was, however, a view shaped by the belief that all young women should be taught in school to fulfil ‘traditional’ domestic roles rather than working as men did. She wrote that “poor country-women, pressed by want, have fallen into the common illusion, that they are certainly the richer for earning money”.

The Austins moved to Weybridge in 1848, and eleven years after this Sarah’s husband died in 1859. Sarah continued living alone at ‘Nutfield’ in Heath Road, and while there she used his notes to complete and publish the conclusion of his work on the ‘Ethics of Jurisprudence’ (1861).

After her death at ‘Nutfield’ in 1897, Austin was buried in Weybridge Churchyard. Her legacy, however, continued through her daughter Lucie, who went on to translate works of German literature.

Photograph of Nutfield, Heath Road, Weybridge, c.1958.

Photograph of the rear view of Nutfield, Heath Road, Weybridge.

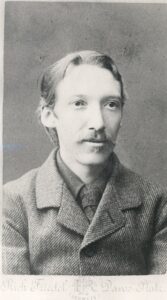

Robert Louis Stevenson c.1880s.

Robert Louis Stevenson is perhaps most known for his adventure novel ‘Treasure Island’ of 1883. The famous story has since been adapted into film many times, and still has a hold over the popular imagination.

Although Stevenson was originally from Edinburgh and wrote most of ‘Treasure Island’ at Kinnaird Cottage in Pitlochry, it was in Weybridge that he corrected the proofs of the novel before it was published. During his stay at The Hand and Spear Hotel near Weybridge Station in 1881, Stevenson worked on the future bestseller from his Davenport writing desk, which is now preserved in Elmbridge Museum’s collection.

“My mouth was empty, there being not one word more of ‘Treasure Island’ in my bosom and here were the proofs of the beginning already waiting for me at the Hand and Spear. There I corrected them, living for the most part alone, walking on the heath at Weybridge on the dewy autumn mornings, a good deal pleased with what I had done, and more appalled than I can depict to you in words at what remained for me to do.” Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘My First Book’ (1894).

Photograph of The Hand and Spear Hotel, from a newspaper article reporting on Robert Louis Stevenson’s stay there.

Kinnaird Cottage, in Pitlochry, Scotland, where Robert Louis Stevenson wrote ‘Treasure Island’.

Michael, Siegfried and Hamo Sassoon with their father Alfred Ezra Sassoon, 1894

Siegfried Sassoon has strong links to the borough of Elmbridge through his grandparents.

Sassoon David and Fahra (Flora) Sassoon owned the grand Ashley Park estate in Walton, having bought it in the 1860s after moving from what was then British-controlled Bombay, in India. It was in Walton that they brought up their children, with Flora disinheriting two of them as adults for marrying outside of the Jewish faith. One of these children was Alfred Ezra Sassoon, born in 1861 and banished in the 1880s for his marriage to Theresa Thornycroft, an English sculptor of the Catholic faith.

The Entrance Hall at Ashley Park, Walton, prior to demolition in 1923.

Alfred and Theresa’s three children Michael, Siegfried and Hamo consequently rarely stayed at the Ashley Park estate when they were young. After his grandparents’ deaths, Siegfried was finally able to visit the house in Walton, and often made trips to it while calling on his friend E.M Forster, who lived in Weybridge.

Siegfried Sassoon is one of the most well-known poets of the First World War, writing about the horror of his experiences while recovering from shell-shock in Craiglockhart with friend and fellow poet Wilfred Owen. The death of Siegfried’s younger brother Hamo at Gallipoli in 1915 devastated him, and, although known for his bravery as a soldier, he grew to deeply resent the war and the motives of those in charge of it.

Read about the Sassoons in the Objects of Empire online exhibition

Photograph of E.M Forster’s house on Monument Green, taken in 1982—roughly 50 years after the author’s occupation of it in the early 1900s.

A member of the influential Bloomsbury Group, Edward Morgan Forster was born in London and led an incredibly interesting life as a young man at home in Weybridge, which is reflected in many of his novels.

Forster is now seen as one of the most important homosexual British authors, although he never ‘came out’ and his sexuality was not widely recognised until after his death. Many of his views on the topic are explored in his essays and shorter stories. One of the most famous of these, ‘Maurice’, was a gay love story inspired by his own relationships and struggles. Despite being written in 1913-14 while he was living at Monument Green, it was only published after his death in 1970. The story was highly controversial due to the fact that homosexuality had only been partially decriminalised three years before this in 1967, and homophobic laws and attitudes were still widespread.

From 1904 to 1925, Forster lived at 19 Monument Green in Weybridge with his mother, Alice Clara Forster, and it was here that he completed all of his novels. Some of the most famous of these, such as ‘Howards End’ (1910) and ‘A Passage to India’ (1924), are still studied by students today and have since been adapted into films.

Discover one of Forster's famous novels in the Objects of Empire online exhibitionFor much of history, girls did not receive the same education in reading and writing as boys did. Until recently, women were traditionally expected to remain housewives instead of performing paid work, and their education consisted of domestic training in how to perform this role. Female authors were consequently rarer than male ones, and many women who did write had to use male pen names in order to have their work published.

Front cover of ‘Silas Marner’ by George Eliot, given to Frederica Gill by her mother in 1877.

This was the case for author George Eliot, whose real name was Mary Ann Cross. She published seven popular novels in the Victorian era, the most famous of which are ‘The Mill on the Floss’ (1860), ‘Silas Marner’ (1861) and ‘Middlemarch’ (1871).

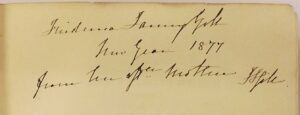

Although George Eliot has no personal connection to Elmbridge, we know that her work certainly had an impact here. This copy of ‘Silas Marner’ contains a touching handwritten inscription inside the front cover, which reads “Frederica Fanny Gill, New Year 1877, from her mother F.S Gill.”

The Gills were an affluent family who lived at Apps Court in Walton. Fanny Susanna Gill had four daughters in total, all of whom were well educated. This book was clearly an important gift to her eldest child, Frederica, and demonstrates how novels by female authors were being circulated amongst women, and how some young women across the borough were beginning to discover, consume and support works by these emerging authors.

Frederica went on to dabble in creating her own personal literature when she made the Gill family album in 1889. It contains an extensive manuscript account of her father Robert Gill’s life, and includes photographs, drawings, letters and newspaper cuttings from the family’s days in Walton. Frederica’s mother clearly still supported her literary engagement, because at the back are a number of pages written by her.

Inscription inside ‘Silas Marner’, which reads ‘Frederica Fanny Gill, New Year 1877, from her mother F.S Gill’.

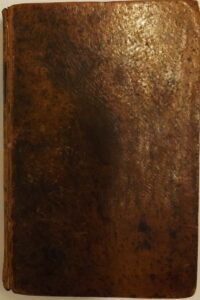

The front cover of ‘Knox’s Essays Moral and Literary’, printed 1815.

The new trend of reading for pleasure exploded in the Georgian era, with the growth of epistolary culture and rising literacy amongst men and women. ‘Pamela’ by Samuel Johnson (1740) was one of the first ever adult fiction novels to be published for entertainment purposes. Its epistolary style explored the changing roles of women in contemporary society, and it was extremely popular among literate middle class women.

As novel reading became more widespread, so too did backlash towards it. This hardback book entitled ‘Essays Moral and Literary: Volume I’ is by Vicesimus Knox, and was printed towards the end of the Georgian era in 1815. It is one of two leather bound volumes of Knox’s Essays in Elmbridge Museum’s collection, which contain an assortment of essay critiques on literary culture and morality.

In essay number 14 Knox makes a particularly fierce critique “On Novel Reading”.

Writers and commentators such as Knox were worried that fantasy novels and fiction would distract schoolchildren, causing them to lose interest in their scholarly pursuits. Women, in particular, were considered to be especially vulnerable to the effects of reading for pleasure because of the notion that their brains could be more easily led astray or corrupted by frivolous and immoral fictional tales.

The contents page of ‘Knox’s Essays Moral and Literary’, printed 1815.

For Knox, this was particularly true of the novel ‘Pamela’:

This edition of Knox’s work was for a long time kept in the collection at St. James’ Church in Weybridge for some of its religious commentary. It was donated to the museum’s collection in 1975.

Print of Fanny Kemble, 19th century, after Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Print of Fanny Kemble, 19th century, after Sir Thomas Lawrence.

One of the most prominent literary activists to come out of Elmbridge is Victorian actress and writer Fanny Kemble.

In November 1807, Fanny was born in London to a family of actors. Both of her parents were in the profession, with her father managing a theatre in Covent Garden. It was not long before the appeal of country life brought the Kembles to Weybridge, where they lived at ‘Eastlands’ from 1825 – 1829, just a stone’s-throw from their family friends the Ellesmeres who lived at Oatlands House. Fanny provided a fascinating and detailed account of life in Weybridge in her memoir, ‘Records of a Girlhood’, in 1878. It is certainly one of the most interesting primary accounts we have of local life there in the Victorian era.

Read extracts from the book here"I followed no regular studies whatever during our summer at Weybridge. We lived chiefly in the open air, on the heath, in the beautiful wood above the meadows of Brooklands, and in the neglected, picturesque inclosure of Portmore Park, whose tenantless, half-ruined mansion, and noble cedars, with the lovely windings of the river Wey in front, made it a place an artist would have delighted to spend his hours in."

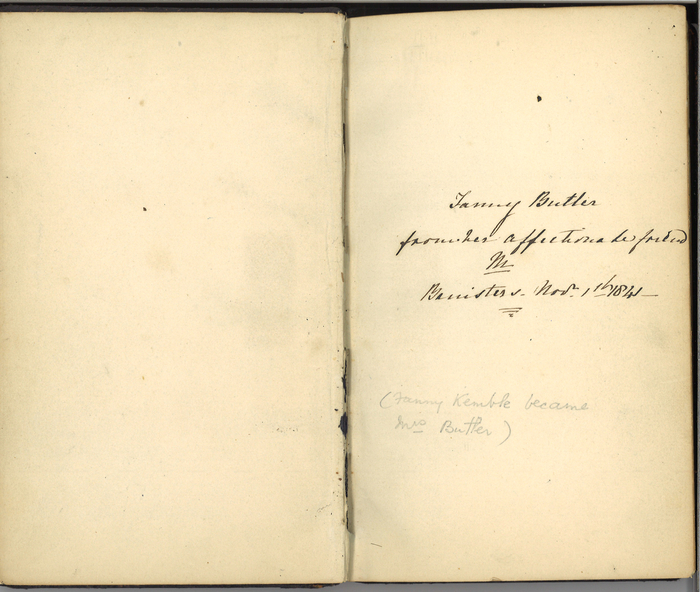

Inside cover of Fanny Kemble’s Apocrypha, inscribed to ‘Fanny Butler from her affectionate friend M. Banisters Nov. 1st 1841.’

It is not, however, for her ‘Records of a Girlhood’ that Fanny Kemble is best known.

From the age of 19, Fanny gained fame and notoriety for her acting skills in Britain, playing lead roles in a number of Shakespeare plays. The profound impact of Shakespeare’s writing on Kemble’s life is evident from her ‘Apocrypha’ held in the Elmbridge Museum collection. This was a book of passages originating from the Greek version of the Old Testament, which were left out of the Hebrew Bible. They were sometimes used by Christians as a means to further study or instruction in the faith, but their status among different denominations varies. Kemble’s Apocrypha was clearly treasured and keenly studied, as it contains many notes in its margins, some of which reference passages from the Shakespeare plays which had such a huge impact on her life and were her trademark as an actress.

The cover of Kemble’s Apocrypha.

Kemble’s success brought her to the United States, where she met and married cotton and rice plantation owner Pierce Butler in 1834. By 1838, the couple had two daughters, and the marriage was beginning to face difficulties. During the four months that the family stayed at one of Butler’s plantations in Georgia from 1838-9, Fanny was appalled by the suffering she saw inflicted upon the enslaved people forced to work for her husband’s family. She wrote about the horrors she witnessed in a journal, which was published long after divorcing her husband, in 1863. It had a huge influence on the case for abolition, bolstering the Unionist cause in the American Civil War which was underway at the time, and securing Kemble’s place in the history of America’s Abolition Movement.

By studying children’s literature, we can learn much about the kind of messages past societies wanted their children to learn.

The 64 historic fairytales in Elmbridge Museum’s archive help reveal the stories which captivated these children of the past. Some, such as ‘Beauty and the Beast’, are tales which have endured. Others, like ‘A Step Into Fairyland’, contain much darker themes, with ‘The Babes in the Wood’ story inside this book ending in the death of two lost children. Below you can find images of a variety of beautifully illustrated fairytales in the collection.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Elmbridge local Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Elmbridge local Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

Given to Louisa Wheeler of Weybridge at Christmas 1903.

Given to Louisa Wheeler of Weybridge at Christmas 1903.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Elmbridge Local Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Elmbridge Local Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

Marked inside the cover 'front Nellie to Lizzie with love, 1908'.

Marked inside the cover 'front Nellie to Lizzie with love, 1908'.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

From a collection of 24 children's books which belonged to Emily Elizabeth Taylor, born 1903.

This was a children's book published in the 1930s.

This was a children's book published in the 1930s.

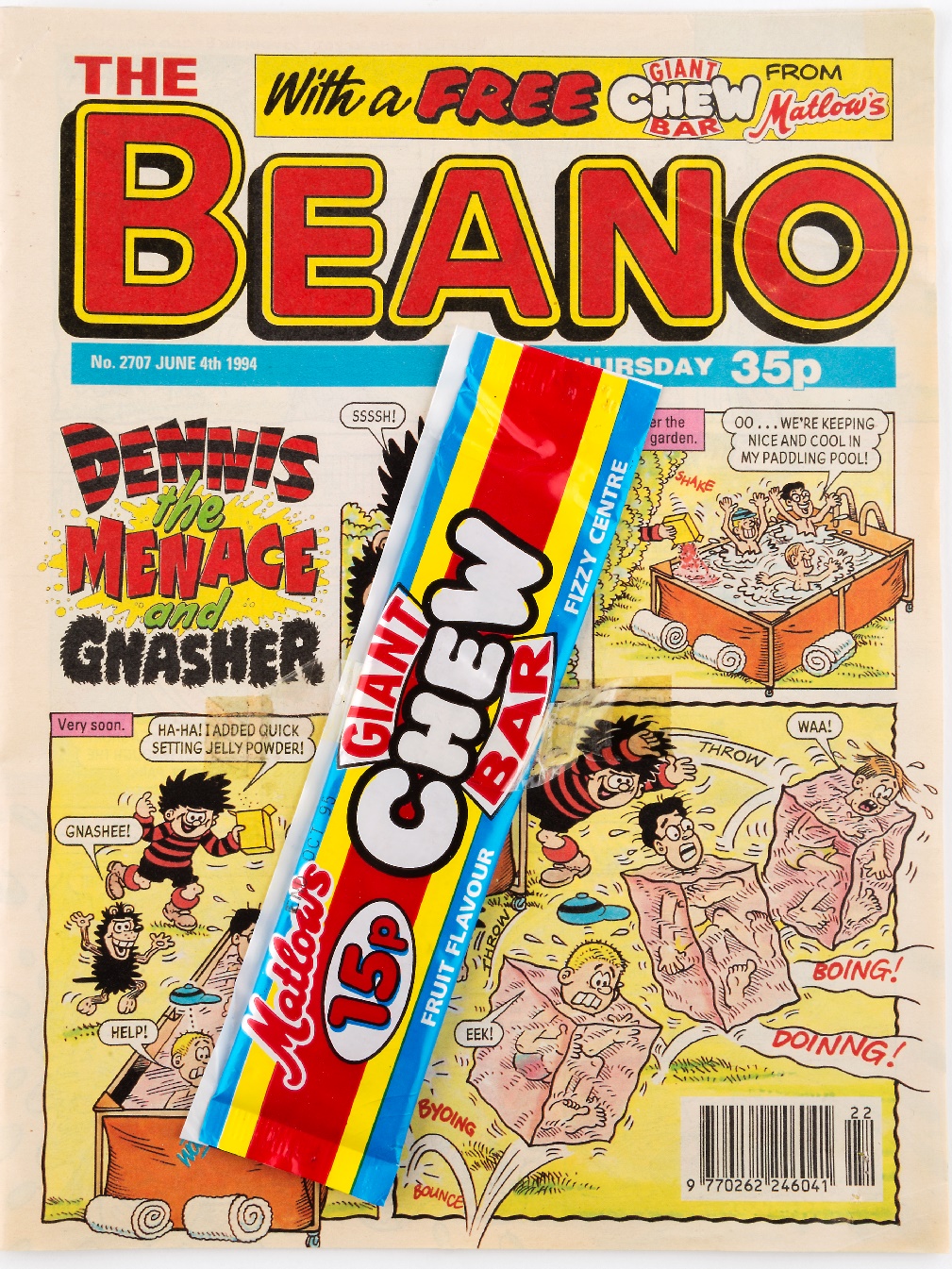

As the 20th century progressed, children’s picture comic books became more popular. ‘The Beano’, with its humorous stories involving regular characters, was a massive hit amongst children in the UK. This one formerly belonged to a child in Weybridge. It is number 2707 from 4th June 1994, costing 35p and with its accompanying Matlows Giant Chew Bar still attached.

When we think of literature, classic novels and academic work may spring to mind. In reality, however, literature permeated the lives of people in Elmbridge in more personal ways. Personal writing such as letters, poems and diary entries now provide valuable evidence of the more intimate details of historic lives.

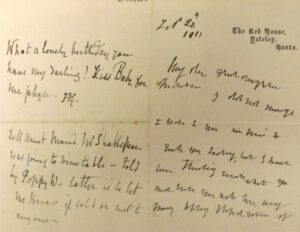

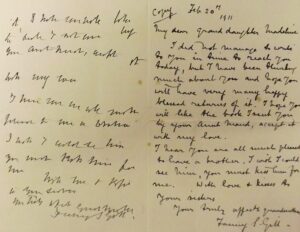

This letter from Fanny Susannah Gill to her grand-daughter Madeline F Gill is dated 28th February 1911. The familial affection in the letter is clear when Fanny talks about Madeline’s recent birthday and her newly born brother.

“Feb 20th 1911.

My dear granddaughter Madeline,

I did not manage to write to you in time to reach you today, but I have been thinking much about you and hope you will have very many happy blessed returns of it. I hope you will like the book I sent you by your Aunt Maud, accept it with my love.

I hear you are all much pleased to have a brother. I wish I could see him, you must kiss him for me.

With love + kisses to your sisters,

Your truly affectionate grandmother,

Fanny S. Gill.”

Letter from Fanny Susannah Gill to her granddaughter Madeline, 1911.

Letters can serve both practical communication purposes and more intimate, personal intentions, such as the expression of thanks, apologies, or well wishes.

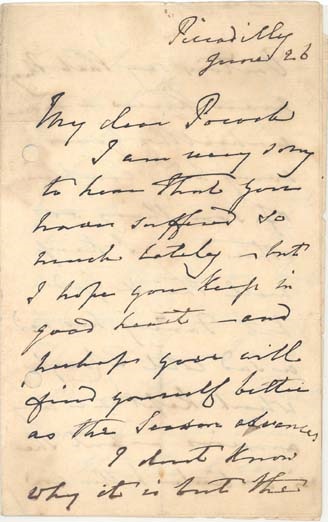

This letter is dated 26th June, and was written by Lady Palmerston to a person named ‘Pocock’ in Weybridge. It was written from 144 Piccadilly, where Lord and Lady Palmerston lived, presumably sent after 1864 when Lord Palmerston’s health was failing.

“My dear Pocock,

I am very sorry to hear that you have suffered so much lately – but I hope you keep in good heart – and perhaps you will find yourself better as the season advances.”

Letter written by Lady Palmerston to a person named 'Pocock' in Weybridge, dated June 26th.

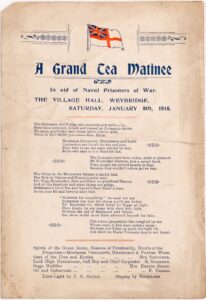

Letter written by Lady Palmerston to a person named 'Pocock' in Weybridge, dated June 26th. As another form of personal expression, poetry can help us to understand the emotions of past people during historic events. The poem on the left is on the front of a programme for a ‘Grand Tea Matinee’ in aid of naval prisoners of war. It was held in the Village Hall, Weybridge, on Saturday 8th January 1916. The poem thanks local traders for supporting the event and also lists those responsible for staging it. As such, it is an excellent primary source for both the information it tells us about local people, and the feelings of those locals towards the First World War and its military personnel.

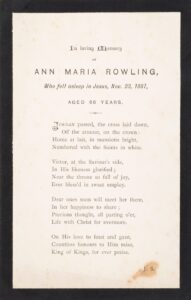

The poem on the right is on a memorial notice for the funeral of Ann Maria Rowling, an Elmbridge local who died on the 23rd November 1887, aged 66. It is often thought that Victorian families did not love each other or grieve in the same way that we do now, due to the frequency of death amongst all age groups within families. Poems and sentimental literature like this memorial show us that this was not the case.

Memorial Notice for Ann Maria Rowling, who died in 1887 aged 66.

Programme for the ‘Grand Tea Matinee’ in aid of naval prisoners of war, held in the Village Hall, Weybridge, 1916.

The Elmbridge Literary Competition run by the R.C Sherriff Trust saw its 17th year in 2022.

Below, we’ve brought together a collection of items which fit the 2022 theme of ‘Enigma’.

The competition closed on the 28th February 2022, but you can continue to make your own literary contribution to this online exhibition in the comment section at the bottom of the page.

Find out more about the yearly Elmbridge Literary Competition‘Enigma’ may also bring to mind the development of science and codes. During the Second World War, the Enigma Machine was used by Nazi Germany to encode their communications, a code which was eventually broken by Polish and British scientists using technology, cryptanalysis and early computers. Below are a selection of items and information related to this theme.

Curious to find out more about children's books, toys and schools of the past?

Childhood in Elmbridge has changed radically since Queen Victoria's reign ended in 1901. Here, we assess the changes and continuities within the lives of local children over more than 100 years.

Submit your own entry!

Fancy having a go at writing your own piece of literature on the theme of 'Enigma'? Submit your ideas, short stories, or poems in the comment section here!You need to be logged in to comment.

Go to login / register